Saved by his steel vest

8 July 2018

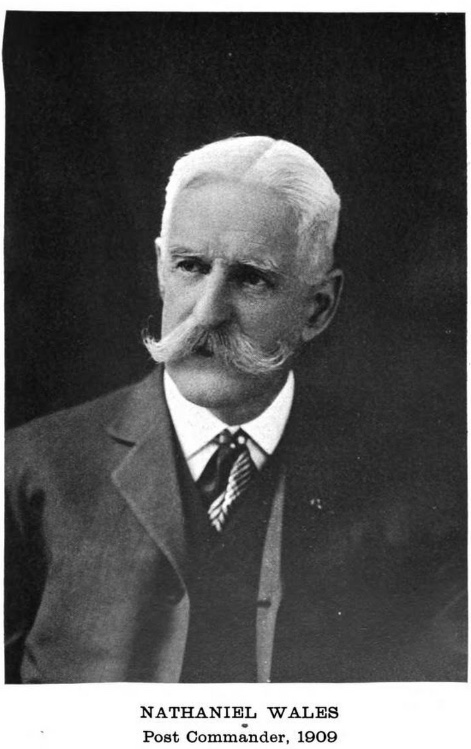

Lieutenant Nathaniel Wales’ story at Antietam may be unique. It is certainly startling: he was saved from a fatal wound by wearing armor at the battle.

I’ve not previously found anything else like this associated with Antietam. Having little experience with the subject, then, I went off to find out something about body armor of the Civil War. As a bonus along the way, I also came upon a number of interesting characters and connections in Wales’ family.

Our man was probably named for his 5x great-grandfather Nathaniel Wales (1586-1681), weaver, who arrived in Massachusetts from Yorkshire, England in 1635. He made the passage in the ship James out of Bristol with other pilgrims including the Reverend Richard Mather (1596-1669), father to Increase, grandfather of Cotton. Wales was later brother-in-law, by the second of his three wives, to Major General Humphrey Atherton. Wales’ descendants were generally successful business people in Boston and nearby towns.

Our Nathaniel’s father Thomas Crane Wales (1805-1880), 7 generations down the line, was prominent in the boot and shoe business, particularly in rubber overshoes and boots. He seems to have been a major player in that market for much of the 1840s and 50s. He had invented and patented a lined, waterproof cold weather boot he called the “Arctic”, which was hugely popular and widely imitated. As a result, I expect young Nathaniel had the benefit of a well-to-do Boston upbringing and education.

He was a salesman in Dorchester when the Civil War began, and also belonged to a Boston militia company called the New England Guard. He was 18 years old when he enlisted as First Sergeant, Company G, 24th Massachusetts Infantry in September 1861. He looks to be a very self-possessed young man.

Before he left the Commonwealth with his Regiment in December, his father presented him with what Nathaniel called a “steel vest” – steel plate body armor.

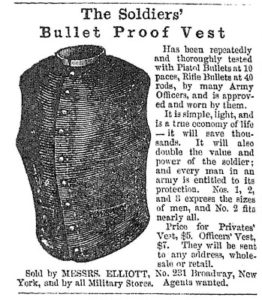

The picture at the top of this post shows the configuration of a typical set of such armor. It was made of steel plates of just under 1/16 of an inch thickness (.057″), and weighed about 8 pounds. It was a breastplate only, and did not protect the sides or back of the torso. The armor was covered with – or worn under – a suit or uniform vest.

At least two companies began to manufacture these in New Haven, CT, in 1862, and remained the largest manufacturers during the War. They were the Atwater Armor Company, which made 200 sets a day at their peak, and G&D Cook, who were the largest horse-drawn carriage makers in the county at the time. G&D Cook sold a lot of these in the southern states, marketing their models by such names as “The Pride of the South” and “The Plantation”. Both of these firms, and their competitors, advertised heavily in Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and other popular periodicals, sometimes making unfounded claims about their effectiveness.

And they sold thousands of them.

So why are references by soldiers to these so rare in Civil War literature? Probably because they were not as widely used as their sales might suggest, but also because they were not something most soldiers would have been proud to talk about. Thousands may have been purchased, but relatively few were actually worn in combat, most having been left behind or cast aside on the march. There are two major reasons for this.

The first and most practical is that the average infantryman was already carrying 40 or more pounds of gear, rations, ammunition, and his weapons, and often marched 10 or more miles a day. In addition to being hot and uncomfortable to wear, armor added another 8 or more pounds to the soldiers’ burden – not something most were willing to carry. At least not for very long.

Second, and perhaps more critical, was the stigma that apparently attached to armor: that its use was “unmanly” or even cowardly. Bravery was an especially important value for soldiers of the period, at least as seen in their writing: being seen as manly and brave was a key measure of self-worth and success for many of the men.

I’ll bring this back to Nathaniel Wales.

After about 9 months service in the 24th Massachusetts in North and South Carolina with General Burnside’s Ninth Corps, he was appointed First Lieutenant in Company H, 32nd Massachusetts in July 1862, but was shortly after transferred to the newly forming 35th. He mustered as First Lieutenant and Adjutant, 35th Massachusetts Infantry on 21 August 1862. The next day the 35th left camp in Lynnfield for Washington, DC, and soon after marched into Maryland. Wales had been sick in hospital immediately before the battle of Antietam, but he rejoined his unit on or before 17 September, carrying an Enfield rifle and saying he wanted to “get a lick at the rebs”.

In a letter to Dr. Bashford Dean, author of Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare (1920), Wales later described his experience at Antietam:

I had been presented with a steel vest by my father when I left Massachusetts, but I left it in Washington. When I entered the fight a brother officer, who was wounded, insisted on my putting on his steel vest. … When I advanced [in the open to meet a rebel charge on the twenty-first Massachusetts regiment] a bullet [evidently at close range] struck me just below the heart … knocking me down. Getting on my feet I walked back to where General Ferrero was lying behind a ledge. As I passed him he said, ‘Where are you going, adjutant?’ I replied, ‘I am hit, sir.’ ‘Where?’ I pointed to the hole in my coat and he said, ‘You had better go to the rear.’ I sat down remarking, ‘I’ll see how badly I am hurt.’ It was not until I grasped the cartridge-box belt to unclasp it that I realized I was wearing the steel vest. The convex side of the dent had cut through vest, shirt and undershirt making a small cut in the flesh. It was considerably swollen and for ten days or a fortnight I was unable to draw a long breath.

Dr. Dean noted that “the drawing of the armor which accompanies the notes of General Wales shows that his escape was the luckier since the bullet struck the breastplate very close to the point where four plates came together, a region of structural weakness in armor of this type, for the free corners of the plates are held together only by rivets.”

Wales also commented:

… it [armor] was worn more often than we had any idea of, but many officers felt they should not be protected better than their men, consequently those who wore the armor did not advertise it … two of as brave officers as I ever knew wore it, my colonel … and my major, who was killed, a bullet grazing the bottom edge of the vest and passing through his body.

[It’s not clear who these officers were. His Colonel, Wild, was wounded at South Mountain on 14 September and lost an arm. Major Carruth was also wounded at Antietam, but survived the War.]

Adjutant Wales remained with his Regiment, and was captured near White Sulphur Springs, VA on 14 November 1862. He was paroled, exchanged, and returned to duty on 21 February 1863. He was commissioned Major on 25 April 1863. He resigned and was discharged on 9 May 1864.

Late in the War he was honored by brevets to Lieutenant Colonel and Colonel (13 March 1865) for his actions while commanding the Regiment at the siege of Knoxville.

After the War he returned to his life-long home in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston. He married Susan Elizabeth Stratton (1844-1901) in 1866 and they had two children, George and Alice.

By 1876 he was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (MVM), and was promoted to Colonel in 1878 and Brigadier General in 1882. He was also active in two veteran’s groups: the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the US (MOLLUS), and the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). He was Commander of GAR Post 113 in Boston by 1909.

His first wife Susan died in 1901, and he married Ellen Lunt Monroe (1872-1946) in 1904. Almost 30 years his junior, she bore him a daughter, Ellen, known as “Jerry”, in 1906. He was then 63 years old. He lived to be 81, dying in 1924 in Boston.

___

Daughter Jerry married Howard Thayer Kingsbury, Jr. in 1930. Known as “Ox”, he had been a rower at Yale, where he graduated in the Class of 1926.

I hope both my readers will pardon me while I roam a little off the track of the battle of Antietam to introduce you to some interesting things about Wales’ son-in-law and his classmates.

“Ox” was a member of the famous 1924 rowing team from Yale. In that year they beat other college teams and the Navy 8 – which had won the gold medal in the 1920 Olympics – to qualify for the 1924 Summer Olympic Games in Paris, representing the United States. They won the gold medal there in races on 13 – 17 July 1924 on the river Seine.

Left to right they are: Leonard G. Carpenter, bow (Class of 1924); Frederick Sheffield, No. 2, (’24); Alfred M. Wilson, No. 3, (’25); J. Stillman Rockefeller, No. 4, captain, (’24); J. T. Miller, No. 5, (’25); Howard T. Kingsbury, No. 6, (’26); Benjamin M. Spock, No. 7, (’25); Alfred D. Lindley, stroke, (’25); and Laurence R. Stoddard, coxswain (’25).

You’ll probably recognize at least two other names on that crew …

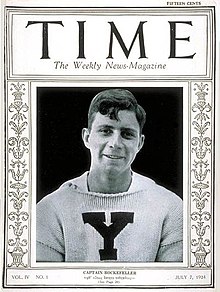

James Stillman Rockefeller (1902-2004), of that famous family, went on to lead First National City Bank (now Citi), and lived to be age 102. As Captain of the gold medal team, he was featured on the cover of Time magazine on 7 July 1924.

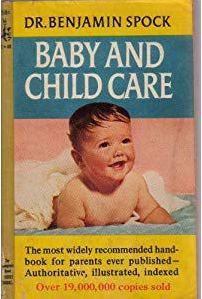

Dr. Benjamin McLane Spock (1903-1998) was the best known pediatrician of the 20th century, publishing his best-selling book Baby and Child Care in 1946. He had made it on to the gold medal boat at the last minute as a substitute. He was a prominent progressive social activist in the 1960s and 70s, and lived aboard sailboats for much of his later life. He lived to be 95.

Howard “Ox” Kingsbury (1904-1991) had a long and successful career as teacher, rowing coach, and headmaster, and died in 1991. Ox and Jerry had adopted a baby boy, and they named him Nathaniel Wales Kingsbury (1940-1998).

Antietam veteran Nathaniel Wales’ daughter Ellen Wales “Jerry” Kingsbury long outlived her husband, going strong to the incredible age of 106 years, passing away in 2013.

Just 5 years before this post.

___________________

Notes

Nathaniel Wales’ bio page is on Antietam on the Web.

Details about armor of the Civil War era and quotes from Wales about his experience with it are from Dr. Bashford Dean’s book Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare, published in 1920 for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Figure 15 above is from that book, and shows a set of armor in a museum in Richmond, VA. The volume is online from the Internet Archives. If you are in the neighborhood, you can find a set of similar armor at the Virginia Museum of the Civil War, New Market, VA.

See more about the association of cowardice and armor in a fine post by Wofford University students Hannah Jarrett and Stephanie Walrath, Class of 2012. They are also the source of the newspaper advertisement pictured here, from Harper’s Weekly of 15 March 1862.

More about the failure of armor to be effective during the Civil War from a post by Sarah Weicksel on the Smithsonian’s Oh Say Can You See blog.

Wales military record is from the Massachusetts Adjutant General’s Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in the Civil War (1931-35), the History of the 35th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers (1884), and the GAR’s What One Grand Army Post has Accomplished: History of Edward W. Kinsley Post, No. 113 (1913).

Some family details from his daughter Jerry’s obituary, from legacy.com.

For more information about the 1924 Yale crew, see a sequence of posts [Pt. 1] on Hear the Boat Sing, a superb rowing blog. I also used details online accompanying the boat picture here: a postcard in the Yale University Library’s Digital Images Database.

July 9th, 2018 at 11:54 am

Great read Brian!! You do an amazing job researching all this information and pulling it together.

September 7th, 2018 at 5:40 am

My reply is unrelated to this blog, but when I googled for Daniel Ohnmacht, I saw that you don’t have a photo of him. I have a picture of a soldier with that name. How can I send it to you?

September 18th, 2018 at 11:13 am

Hi Donna – I’ve sent you an email, also. Anyone with a photo or other information about an Antietam soldier may scan it and send it to me by email: bdowney at aotw dot org