Antietam faces, artillery edition

9 May 2019

Lieutenant Evan Thomas commanded the consolidated Batteries A and C of the 4th United States Artillery on the Maryland Campaign.

He was the 3rd son of US Army Colonel and Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas (USMA 1823), and at the start of the War in April 1861 received a commission as 2nd Lieutenant, 4th United States Artillery. He was promoted to First Lieutenant in May. He was then just 17 years old.

He was assigned to Battery C which, due to a manpower shortage, was consolidated with Battery A in October 1861. He was in action with his battery on the Peninsula in mid-1862 and succeeded to command by order of seniority sometime after Captain Hazzard died of wounds in mid-August 1862. Evan had just celebrated his 19th birthday.

Here’s Lieutenant Thomas with a group of his fellow officers taken at Sharpsburg in September or October 1862, shortly after the battle of Antietam:

The caption on the picture is Lt. Rufus King, Lt. Alonzo Cushing, Lt. Evan Thomas and three other artillery officers in front of tent, Antietam, Md. (click to enlarge) There is no guide to who is who, but I have had some expert help working to identify them.

CWArtillery gets new home

7 December 2009

Bad news and good news. The bad news is that the famed website cwartillery.org is no more. The good news is that the core information – if not the lively, efficient design – is still available online.

header, The Civil War Artillery Page, 1999 (C. Ten Brink)

Unfortunately, original author Chuck Ten Brink can no longer maintain the site, but he has passed the material to the care of the Robinson Artillery. It begins on their Civil War Artillery page.

Chuck first put his work on the subject on the Web in 1996, and has been thereafter the go-to guy for many of us on terminology, equipment details, guns and artillerists, and (in partnership with Wayne Stark) the Civil War Artillery Encyclopedia and the National Register of Surviving Civil War Artillery (sample: Antietam’s page c. 1998).

I’ll very much miss the old site, but say Hurrah, Chuck, for your long online service!

Horatio Gibson of the Flying Artillery (1)

5 May 2008

James F. Gibson, of Mathew Brady’s Washington studio, took a lot of photographs as he traveled with the Federal Army on the Virginia Peninsula in early summer 1862. Among these are a number with particular interest in artillery and artillerymen. Well represented among them are Horatio Gates Gibson and his command, the combined Companies C and G of the Third United States Artillery.

Capt. H.G. Gibson, 3d US Artillery, June 1862 (James F. Gibson, Library of Congress)

This is Regular Army Captain Gibson in the midst of his command in June 1862. It’s a detail from a stunning picture of the entire battery of six 3-inch ordnance rifles and the nearly 100 officers and men who were present on campaign. Gibson and many of these were in action from the Peninsula through Antietam and Gettysburg to Appomattox Courthouse with the Army of the Potomac.

Notable Rhode Island artillerymen

22 January 2008

Just a quick post this week – I’ve too many irons in the fire. Blog neglect aside, though, January has been a good month for incoming treasures and catching up with biographies on AotW.

Corporal James A Barber (M. Frazel)

One in particular came out of a post I found on Granite in my Blood just before Christmas in which Midge Frazel transcribed a relative’s narrative about the Barber Family. Included was her great-grandfather James Albert Barber, who was in Battery G, First Rhode Island Light Artillery…

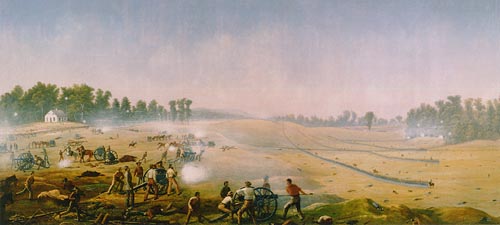

Federal artillery east of the Antietam

30 November 2007

Artillery Hell (James Hope, Antietam National Battlefield)

A few days ago I was prompted by a TalkAntietam query to look into the strength of the Federal Artillery at Antietam on 17 September 1862. In particular, that of the long-range guns overlooking the battlefield from the heights east of Antietam Creek.

Those guns were largely responsible for Sharpsburg’s reputation–at least among Confederate artillerymen who survived–as “Artillery Hell”. Their impact on the battle was significant, and they loom large in most battle narratives, but just how many were there?

Rufus Pettit: solid artilleryman, vicious jailkeeper

28 October 2006

I should avoid online Civil War discussion groups. They just give me more research threads to pull. Like I need more.

I’d been following a discussion about artillery over on the American Civil War Message Board. I was thinking I could contribute on a question about unit organization, which referred to Battery B, 1st New York Light Artillery, as an example.

R.D. Pettit, c. 1861-65

First, I looked to see what that battery was doing at Antietam, and noticed the commander was Captain Rufus Petit (above). I didn’t have much on the Captain, but did know that he had been dismissed from the service in 1865. I wondered why. He seemed to have served honorably on the Peninsula and at Antietam. “Dismissed” is usually bad.

Corporal Farmer gets a new stone

16 April 2024

This is the first time I’ve seen this in many years visiting Antietam National Cemetery: an obvious replacement headstone. And not just because of wear and tear. An Ohioan in a row of Connecticut soldiers.

There’s a great story here, I’m sure, but I only know part of it.

William Whitney Farmer, 34, of Wakeman, Ohio enlisted as a Corporal in Company D, 8th Ohio Infantry in June 1861, and was killed by artillery at Antietam on 16 September 1862. He was mis-identified as being in the 8th Connecticut Infantry when he was removed from his resting place on the battlefield and re-buried in the new Antietam National Cemetery in 1867.

Here’s the headstone that’s been over his grave since then:

On my visit last Friday, though, this brand new, fresh cut stone jumped out at me:

I hope a reader will let us know how this came about. You won’t be surprised to hear there are many, perhaps hundreds of headstones in the Cemetery with errors large and small, and I would never have expected the Park Service or the VA to replace any of them.

And yet … here we are.

Notes

The photos above of Farmer’s new headstone are by the author, taken at the Antietam National Cemetery on Friday 12 April 2024.

His original headstone photo is from contributor Birdman on Farmer’s online memorial at Find-a-grave.

The page image here is from the 1890 version of the History of the Antietam National Cemetery, including a descriptive list of all the loyal soldiers buried therein …, published by George Hess, late Private, 28th Pennsylvania Infantry; online from the Library of Congress. His work is a virtual copy of the History published by the Cemetery Board of Trustees in 1867, except that Hess noted the headstone numbers, which I find more useful than the section/lot/grave numbers in the original volume.

Maryes in Maryland

8 April 2024

Here’s Lieutenant Edward A. Marye‘s (probably pronounced “Mary”) family home in Fredericksburg, VA as it looked in May 1864, then in use as a Union military hospital for troops wounded during the battle of the Wilderness.

First Lieutenant E.A. Marye (1862)

His father John Lawrence Marye (1798-1868), a successful lawyer and mill owner, bought land and a small house on a hill overlooking Fredericksburg in about 1824. He improved the house and named it Brompton, after the Middlesex village in England from which his Hugenot-Norman great-grandfather Rev. James Marye (or Jacques Marie, 1692-1768) came to America in about 1730.

The high ground around it became known as Marye’s Heights – now famous for the combat there in December 1862.

Lt. Edward Marye commanded a section of 2 3-inch Ordnance rifles of the Fredericksburg Artillery (Brig. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Division) at Harpers Ferry (14-16 September) and Shepherdstown (19 September), and led the battery at least part of the day at Sharpsburg (17 September) while Captain Carter M Braxton acted as Hill’s chief of artillery.

But there were also 4 other Maryes in the battery …

Private Alfred James Marye, Edward’s nephew, was on the Maryland Campaign and was wounded by counter-battery fire at Boteler’s Ford on the Potomac on 19 September. He was barely 16 years old. He served with the battery to the end of the war and was afterward a railroad clerk in Montgomery County, VA.

Private Alexander Stuart Marye (1841-1915), a younger brother of Edward’s, enlisted in the battery in June 1862 and was probably in Maryland in September. He was on detail away from his unit on ordnance and administrative duties for most of the rest of the war and was surrendered and paroled at Greensboro, NC in May 1865.

John Lawrence Marye, Jr. (1823-1902), also Edward’s brother, enlisted as a Private in April 1861 and was promoted to 5th Sergeant in April 1862. He was absent, sick into October 1862, so probably not in Maryland, but was surrendered and paroled with the battery at Appomattox Court House, VA on 9 April 1865. During the war he also served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1863-65). He’d been a wealthy lawyer and farmer in his own right before the war, and Mayor of Fredericksburg in 1853-54. He was afterward again a Delegate (to 1868) and Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1870-74).

Another of Edward’s nephews, his oldest brother James’ son Private William Nelson Marye (1841-1929) enlisted in Braxton’s Mounted Artillery (later Fredericksburg Light) on 12 May 1861, but was detached from his unit for much of 1862 and probably not with them in Maryland. He was with the battery from March 1863 to September 1864, when he was again detailed, as a clerk to a military court for the 3rd Army Corps, but was back by Appomattox in April 1865.

To complete Edward’s story: he was promoted to Captain and it became his battery in March 1863, but he did not survive the war; he died of disease in Petersburg, VA in October 1864.

Notes

The photograph above of the Marye house “Brompton” is from the Library of Congress.

Details about Brompton from its National Register of Historic Places nomination form [pdf]. The home was acquired by Mary Washington College (now University) in 1947 and it is now their president’s residence.

Lieutenant Edward Marye’s picture here is an ambrotype in the collection of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond.

The Maryes’ military records are found in the US War Department’s Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers, Record Group No. 109, Washington DC: US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Lt Columbus W. Motes, his horse, &etc

2 April 2024

A 25 year old professional photographer from Athens, GA, Columbus Washington Motes was First Lieutenant and commanded a section – two rifled guns – of the Troup (Georgia) Artillery on the Maryland Campaign of 1862. On 14 September he helped muscle his guns to the crest of Elk Ridge then down the ridge to Maryland Heights overlooking Harpers Ferry, where they contributed to the bombardment of the Federal positions in and around the town. The garrison surrendered the next day.

He fought his guns again near the Dunker Church at Sharpsburg on the 17th. He was seriously wounded there, at first refusing to leave the field. As his Captain Henry H. Carlton later remembered it:

[H]e came to me, his arm dangling by his side, and covered with blood and said: “Captain Carlton, what do you think? The yankees have shot me!” I ordered him to the rear, but he returned to his post, and in a few moments I heard: “Captain Carlton, the yankees have shot me again!” This time he was badly wounded in the hip, and was borne to the rear on a caisson.

He had recovered and returned to duty by the end of the year, and on 3 January 1863 the other three officers of the battery, Captain Carlton and Lieutenants Jennings and Newton constituted a Board of Survey and Appointment “to assess the value of a horse belonging to Lt Motes which was killed in action @Sharpsburg Md Sept. 17th, 1862.”

The findings of the Board (they filled in “Two Hundred” as the amount, which is hard to read) as approved by brigade commander Wofford:

He did collect the $200 for his horse, late in 1863, by which time good horses were worth as much as 10 times that amount. I do not know what he paid for a replacement.

Lieutenant Motes was probably carrying this image of his sweetheart in Maryland, as he apparently did through the war:

She’s Emily F “Emma” White, also of Athens. Motes was briefly married before the war and had a daughter born in 1857, but his wife died by 1861. He married Emma shortly after the war, in 1866, and they spent most of the rest of their lives making photographs in Atlanta.

Notes

Thanks to Jim Rosebrock for the pointer to Lieutenant Motes in his excellent book Artillery of Antietam (2023), published by the Antietam Institute, which got me started on the Lieutenant.

The Carlton quote above is from the Atlanta Constitution of 11 May 1890, when Carlton was US Congressman from Georgia.

The findings of the Board of officers is from Motes’ Compiled Service Record jacket at the National Archives; I found it online from fold3.

The ambrotypes of Columbus and Emma, above, are from the Atlanta Historical Society’s Journal of Summer, 1981. The text accompanying them on pages 42 and 43 reads:

C.W. Motes (1837-1919) and Emma White Motes (c.1830- c.1890)

” . . . a small red morocco case, containing a Collodion portrait ofthe girl he left behind him, was valued by him above gold and precious stones.” Written in 1855 to describe a soldier of the Crimea and the photograph he carried with him, this quotation could as easily have been ascribed to soldiers of the American Civil War and the photographs of loved ones that they carried. Columbus W. Motes of Athens, Georgia, a first lieutenant, then captain [sic], with the Troup County Artillery, carried a small ninth-plate ambrotype with him throughout the war. “Presented by Miss Emma White, 1861,” the photograph carries with it the almost traditional tale of having halted bullets intended for its bearer. Miss White’s ambrotype survived the war in excellent condition and was brought to Atlanta one decade later by the captain and Emma, who were married in 1866.

While in Athens, Motes, an artist, had begun the business of photography with a man named White, possibly Emma’s brother or father. The photographs reproduced here may have been taken in Athens. It was the photography business that C.W. Motes continued, probably with Emma’s help, in Atlanta in 1872 in a gallery on Whitehall Street, “a favorite resort with lovers of art.” One Atlanta newspaper account written soon after the Moteses’ arrival posed the question of “the real” versus “the ideal” when advising its readers, “whether comely or homely,” to call on Captain Motes, who could “make a very homely face look passable.”

In the 1880s, Motes was awarded a bronze medal in a New York competition for photographs created through a short-lived photographic process called the “chromatype.” He was also known for his photographic sculpture using people posed in well-known scenes from literature and mythology. In 1895 Motes won additional prizes for his photographs exhibited at the Cotton States and International Exposition. Before his death in 1919, he had become one of the city’s most popular portrait photographers. Doing a brisk business until 1907, the Motes gallery survived fire, changes in the public’s taste, and changes in photographic processes to become one of Atlanta’s most successful photography shops.

Twelve hundred pounds of corn

18 March 2024

While going through documents in Captain Robert Boyce‘s Consolidated Service Record (CSR) jacket, I came upon this receipt dated “Camp in the field Sept 23d 1862.”

My transcription:

Rec’d of Capt C. McRae Selph aſs [asst] Quartermaster C.S.A. the following articles viz –

Sept 12th 1200# Twelve hundred pounds of corn.

” 13th 1170# Eleven hundred + Seventy pounds of corn.

” 14th 1120# Eleven hundred + Twenty ” of corn.R. Boyce

Capt Lt Battery

Boyce commanded a six-gun battery of the Macbeth Light Artillery on the Maryland Campaign of 1862. The corn was likely forage for his horses. How many horses? A back of the envelope calculation, and I’m no expert …

Minimum 4 horses each for 12 limbers (6 guns, 6 caissons), forge wagon (total 52); Minimum 16 personal horses for Captain, 4 Lieutenants, 8 Sergeants, 2 buglers, 1 guidon; (?) spare horses; total at least 70 horses.

The receipt jumped out because it is the first I’ve seen for forage delivered to a unit while on combat service in Maryland. All sorts of research questions follow, like:

– How many army wagons did it take to haul that grain to Boyce?

– How far did those wagons travel? From Winchester, maybe?

– How long would that much grain have lasted? Assuming about 12 pounds per horse/day (or twice that if no hay) and at least 70 horses, not long.

– How much grain or other forage would all the horses of the Army of Northern Virginia have required? Were they getting it in September 1862?

– Horses cannot long live on grain alone. Was there good pasturage in Maryland? Hay was probably too bulky to transport to the combat zone.

I’d be glad to hear from logistic experts on this.