Dr. Howard and Hooker’s foot

13 February 2010

Because he was conspicuous on his white horse and close to the battle-front on the morning of Wednesday, 17 September 1862 near Sharpsburg, Maryland, perhaps it was inevitable that Major General Joseph Hooker would be killed or wounded in the ferocious combat there.

Major General Joseph Hooker (c. 1862, Library of Congress)

And wounded he was. Although it is fantasy to speculate, there were those who thought the battle of Antietam would have gone differently had Hooker not been knocked from command of the Federal First (I) Army Corps by a bullet through the foot at about nine o’clock that morning.

Sharpsburg, September 20, 1862.

MY DEAR HOOKER: I have been very sick the last few days, and just able to go where my presence was absolutely necessary, so I could not come to see you and thank you for what you did the other day, and express my intense regret and sympathy for your unfortunate wound. Had you not been wounded when you were, I believe the result of the battle would have been the entire destruction of the rebel army, for I know that, with you at its head, your corps would have kept on until it gained the main road. As a slight expression of what I think you merit. I have requested that the brigadier-general commission rendered vacant by Mansfield’s death may be given to you. I will this evening write a private note to the President on the subject, and I am glad to assure you that, so far as I can learn, it is the universal feeling of the army that are the most deserving in it.

With the sincere hope that your health may soon be restored, so that you may again be with us in the field, I am, my dear general, your sincere friend,

GEO. B. McCLELLAN,

Major-General.

Looking into the nature of the General’s injury led me in a somewhat different direction, however – toward learning about the medical care he received, and more about the life and career of his doctor, Assistant Surgeon Benjamin Douglas Howard, USA …

Doctor Howard had recently joined the staff of General McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, and was present on the battlefield of Antietam. His description of General Hooker’s wound and later recovery is found in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1883). As an aid to understanding the detail, I’ve found some period illustrations and will define some unfamiliar terms as we go.

Oddly, Hooker didn’t notice when he was hit. He later described his feelings of that epic day:

.. The whole morning had been one of unusual animation to me and fraught with the grandest events. The conduct of my troops was sublime, and the occasion almost lifted me to the skies, and its memories will ever remain near me. My command followed the fugitives closely until we had passed the corn-field a quarter of a mile or more, when I was removed from my saddle in the act of falling out of it from loss of blood, having previously been struck without my knowledge …

For reference, here are the bones of the right foot, viewed from the bottom, from Henry Gray’s Descriptive and Surgical Anatomy (2nd ed, 1858, published in the US in 1862). I’ve highlighted the scaphoid (green) and cuboid (red) bones:

human foot bones, plantar surface (Gray’s Anatomy, 1858)

Dr. Howard’s narrative begins

He was wounded in the right foot by a minie ball while leading his command, being on horseback at the time, and standing in the stirrups with his weight thrown on his right foot, which was turned outward. The ball struck the inner side of the foot inferiorly to the middle of the scaphoid bone, passing between the first and second layers of the plantar muscles, almost transversely across the plantar portion of the foot, and emerging inferiorly to the anterior border of the cuboid bone. The bones of the foot were uninjured …

inferiorly to = below, beneath

transversely = crossing at right angles

plantar = the bottom of the foot, sole

anterior = front

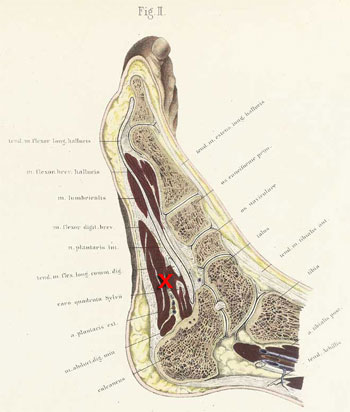

Here’s a sectional view through a foot, from Wilhelm Braune’s Topographisch-anatomischer Atlas (1867-72). An “x” marks my approximation of the point through which the ball passed through General Hooker’s foot.

section through the adult human right foot (Braune, 1867; NLM/NIH)

Dr. Howard continues the story

… On the morning of September 18th, I was sent by the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac [Dr. Letterman] to attend General Hooker, then lying in a farmhouse [probably Pry’s] near the battlefield.

Warm-water dressings had been applied previous to my visit. There was no constitutional disturbance, but the foot was hot and inflamed. By means of a syringe I thoroughly washed out the wound with warm water, and finding it most agreeable to the patient, substituted cold- for warm-water dressings. The next day I found the patient very comfortable; the appearance of the foot had greatly improved and the inflammatory symptoms had disappeared. I then ordered a lotion of plumbi instead of cold-water dressings as being more likely to allay any irritation that might arise in the parts.

warm/cold-water dressings = poultice like treatment for open wounds at 90 º or 60 º F; warm in particular thought to protect against gangrene; at a meeting in 1873, Dr. Howard observed “… irregular application of cold water has induced tetanus and may favor the development of other surgical diseases … based more especially upon his experience at the battle of Antietam where a great amount of tetanus was seen”

inflammatory symptoms = response to injury; characterized by redness, heat, and pain

plumbi = containing lead salts, possibly lead iodide; “…. when applied to the abraded skin, to sores and to ulcers, they [lead salts] coagulate the albumin of the discharge, thus forming a protective coat; they coagulate the albumin in the tissues themselves; and they contract the small vessels; for these three reasons they are powerfully astringent. They also soothe pain, and are therefore excellent local sedatives … ” Materia Medica (1901)

Before the General left that evening, for Washington, I advised him to resume the use of tepid water as soon as all tendency to active inflammation should cease. On October 25th, I heard that tetanic symptoms had manifested themselves, but received a letter from the General a few days afterwards stating to the contrary. On November 25th the General, who had returned to duty in the field, requested me to look at his wound, which still troubled him somewhat. I found the newly formed cicatrices somewhat tumefied; they were painful on pressure, and the General was still unable to mount his horse unaided, though he persisted in being on active duty. On November 30th, I found there had been a steady improvement, and, although the step had not its former elasticity, the wound had left no serious inconvenience behind.

tetanic = of tetanus; illness also known as “lockjaw”; caused by bacteria Clostridium tetani. Dr. Howard later authored a study Notes and observations on tetanus and intermittent diarrhea occurring after the battle, on the field of Antietam (1866), which suggests he gained some specialized experience in the subject there.

cicatrices = plural of cicatrix – scar tissue

tumefied = swollen

The editors of the Medical and Surgical History noted that “General Hooker remained in active service until the close of the war, and was ultimately retired October 15, 1868.”

****************

Benjamin Douglas Howard was born in Chesham, Buckinghamshire, England on 21 March 1836, one of 5 siblings who were orphaned when school-age children. He came to New York in 1853 looking for a college education on the way to his intended career as a medical missionary. He attended Williams College in Massachusetts beginning in 1855, but did not continue to graduation. He then returned to New York, graduating as a Doctor of Medicine in 1858 from the College of Physicians and Surgeons (now part of Columbia University).

Shortly before the War, apparently intrigued by the institution of chattel slavery and its abolition, he traveled to St. Louis and got a job as a clerk in a slave market there. While in that occupation he reportedly helped to get fugitive slaves North via the Underground Railroad, but was found-out, and had to flee the state in fear of his life.

In May 1861 he obtained a commission as Assistant Surgeon in the 19th New York Volunteer Infantry (redesignated 3rd New York Light Artillery in December 1861). He served with them until September, when he was commissioned Assistant Surgeon in the Regular Army.

After Antietam Howard continued in US Army service, including duty as medical purveyor (purchasing agent) and acting Medical Director of the Department of the Ohio, until resigning his commission on 28 December 1864.

By that time he had developed and successfully introduced an improved ambulance design for field use. It’s primary selling point was significantly increased comfort of the patients transported – due largely to internal suspension, but it also offered benefits of decreased weight and lower production costs than the standard medical wagons then in military use.

Howard ambulance, rear and side view, tailgate up, on city street (c. 1864-65, George E. Pell, US Sanitary Comm., NYPL)

This design was an award winner at the Paris Exposition of 1867, and in widespread use in the French Army by 1870 – seeing action in the Franco-Prussian War. Howard was still offering his ambulance at least as late as 1882, when he made a case for a municipal ambulance service for London. It’s not clear how profitable these were for the Doctor personally, but he did enjoy a lifestyle later suggestive of a certain independence that may have been based on income from his design.

Howard ambulance, rear view, tailgate down, with litters, water tank with spigot underneath (c. 1864-65, George E. Pell, US Sanitary Comm., NYPL)

In addition to his work with ambulances and transport of the wounded, he was later cited for his 1863 technique of sealing penetrating or “sucking” chest wounds so as to allow the patient to breathe. In 1869 he also developed a method of artificial respiration, which was later named for him. His direct method saw wide use for as many as 100 years:

Howard’s method. Place the body supine with a cushion under the back so that the head is lower than the abdomen. The arms are held over the head. Forcible pressure is made with hands inward and upward over the lower ribs about sixteen times in a minute. (from Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary, 17th Ed., 1914)

After the War he set up a successful surgical practice in New York City. He was professor and visiting lecturer at medical schools in New York, Ohio, and Vermont, and traveled for research and to present his ideas in Europe. In 1873, however, he became increasingly ill, quit his practice, and traveled in “Europe, Asia, and Africa” to recover.

He then moved to London, and resumed his medical and teaching work there, also using it as his base of operations for continued world travel.

In the 1880s he began a study of prisons and related issues of medical care in them. He traveled widely in that research – most notably to the far eastern parts of Russia, about which he wrote two books: Life with Trans-Siberian Savages (1893) and Prisoner of Russia: a personal study of convict life in Sakhalin and Siberia (pub. posthumously in 1902).

Dr. Benjamin Howard returned to New York to live in 1898, but died of an ailment of the liver on 17 June 1900 at the home of a friend in Elberon, New Jersey. He was 64 years old.

Benjamin D. Howard (c. 1900, from Prisoners of Russia)

_________________________

Notes:

Howard’s description of General Hooker’s wound and treatment is in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Part III, Volume II. (3rd Surgical volume) (1883), page 60. The full set of that History, including this volume, are online from the Internet Archives (IA).

His military service dates are from Heitman’s Historical Register and Dictionary (1903), Vol. 1, pg. 545, which is also online from IA. Further biographical and medical details are from the Preface to his Prisoners of Russia (1902) – written by General O.O. Howard, retired (!) – and his NY Times obituary [pdf] of Wednesday, June 23, 1900, page 7.

The reference to his campaign for a municipal ambulance service for London is from an article in the British Medical Journal of 4 February 1882 , pp. 152-156. Dr. Howard was a frequent contributor to that journal in his lifetime.

I used an online edition of Gray’s Anatomy (1862) and Dorland’s Medical Dictionary (1914) for medical help.

The excellent drawing of the “fleshy” foot above is by Wilhelm Braune (1831-1892), a professor at the University of Leipzig. From a lovely online exhibition of some of his plates hosted by the National Library of Medicine comes the following about his process:

His Topographisch-anatomischer Atlas nach Durchschnitten an gefrornen Cadavern consists of over 30 color lithographs of frozen cross sections of human anatomy, many of them being the most aesthetic of that genre. Of the first plates, Braune states:

“[they are] taken from the body of a powerful, well-built, perfectly normal man, aged 21, who had hanged himself. The organs exhibited no pathological abnormalities. The body, which was brought unfrozen, was placed on a horizontal board. In this position, the subject lay untouched in the open air, and at the temperature of about 50 degrees F., for fourteen days. At the end of this time the process of freezing was commenced and completed.”

After sections were cut, thin paper was placed over them and tracings were made of the anatomical features.

Can you Help? A wartime carte-de-visite (CDV) photograph of Dr Howard was among a large collection sold at auction in 2006 by Cowan’s. Cowan’s doesn’t respond to requests of this type, but if anyone can put me in touch with the buyer – or find us a digital copy of that picture – I’d sure appreciate it.

March 21st, 2010 at 4:08 pm

Interesting! Thanks for posting it.

April 4th, 2010 at 3:22 am

From personal experience I can tell you that dealing with a foot injury is not an easy thing.

Hooker seemed to be injured at key moments during battle. At Chancellorsville he was knocked unconscious by a beam on the porch to his headquarters after it was struck by a cannon ball. Perhaps these injuries took some of the fight out of ‘Fighting Joe.’

Excellent blog and AotW is a very good too. Thanks

October 30th, 2020 at 1:05 pm

Interesting research. I am curious if you have any additional information on Dr. Howard. I am involved in a project related to his activity at the Battle of Second Manassas and was wondering if you have come across any personal diary or writings of his early years? Thanks

October 30th, 2020 at 9:37 pm

Hi Karin,

It’s been a while since I looked into Dr. Howard, but I did not come upon any of his writings from earlier in the war when I was researching this piece. Good hunting!

I hope you’ll comment here again with anything new you find and with the outcome of your project.