On the trail of the Corn Exchange Regiment

5 October 2008

146 years to the day after the historical events, a lucky group of us tracked the unlucky 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers to the places and views of the Battle of Shepherdstown Ford (20 September 1862). Under the capable guidance of Dr Tom Clemens and members of the Shepherdstown Battlefield Preservation Association (SBPA), we waded the Potomac, scaled the heights, and walked the field.

ANB Visitor’s Center – a postcard perfect day

We gathered Saturday the 20th at the Antietam Visitor’s Center, drove in convoy to the Dunleavy spread near Shepherdstown, WV, and then carpooled to the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Canal Park [NPS site] back on the Maryland side of the Shepherdstown (Boteler’s, Packhorse, Blackford’s) Ford…

C&O Canal bed

We walked the towpath of the (now dry) Canal for a hundred yards or so to find a good spot to enter the Potomac River at the Ford. This was the route taken by General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia (ANV) on the night of September 18-19, 1862, back into Virginia after the battle of Sharpsburg.

It was also the crossing point for elements of the Federal Fifth Army Corps – under Fitz John Porter – in their pursuit of the ANV on the 19th, and a more aggressive probe on the morning of the 20th by US Regulars under Major Lovell and the volunteers of Colonels Warren and Barnes Brigades – including the men of the ill-fated Corn Exchange Regiment: the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Tom Clemens sets the stage, and gets his feet wet

On September 19th, a Federal raid across the river had found Confederate General Pendleton’s artillery rear-guard posted on the heights with insufficient infantry support. The Federals captured 4 guns, and panicked Pendleton who rode off to tell his boss of the ‘disaster’. That evening General Lee sent A.P. Hill and his Light Division back toward the Ford to save the artillery and halt the Federal pursuit.

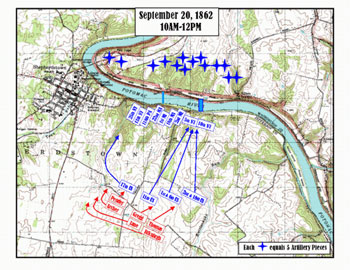

On the morning of the 20th Major-General Fitz-John Porter was ordered to send two divisions over the river to co-operate with a cavalry advance, and scour the country in the direction of Charles town and Shepherdstown. In obedience to these instructions, Sykes, with his division, composed of two brigades of regulars and one of volunteers, was directed to proceed in the direction of Charles town, and Morrell, with Barnes’s brigade leading, in the direction of Shepherdstown. The cavalry did not, however, reach the Virginia side until Sykes’s pickets were in close proximity to the advancing foe.

Sykes crossed the river early in the morning, and Lovell’s 2d (regulars) Brigade skirmishers, advancing a mile into the country, soon developed the enemy, some three thousand strong, approaching with artillery …

The Ford from the Maryland side, lifeguard Mike ready

Our plan was to cross the 200 yards of the Potomac at this point, following the upstream edge of the line of rocks forming the “riffle” seen here. Our gear was all in waterproof containers in case anyone took a dive. No swimmers, though.

View upstream toward the remains of the dam

Into the river we go

We started across the river in water between knee and thigh deep, over a gravel bottom with frequent larger stones; from baseball to bowling ball in size. Passable, but a bit tricky to navigate. Current was moderately swift – I would not have wanted to cross in water a lot higher or faster. Or carrying a forty-pound pack. Or at night, for that matter.

View from halfway across

By halfway we had veered upstream perhaps 20 yards, and found ourselves knee deep in beautifully clear water running over what felt like a paved roadbed. Limestone, I think, in flat sheets. A perfect bottom for wagons, guns, horses and men (and later tourists) all the way across the river. Not hard to see why this was a well-used ford for so many years.

Signs in the gloom on the West Virginia shore

My photo of the Pack Horse Ford historical marker didn’t come out well. Its text says:

Early settlers crossed here. “Stonewall” Jackson and A.P. Hill used this ford on the way to Battle of Antietam. Here Lee’s army crossed after the battle, with the Corn Exchange Regiment, other Federals in pursuit.

A good photo and links to the nearby War Department markers can be found in Craig Swain’s contribution at the Historical Marker Database (HMDb).

The 118th Regimental history helps set the scene around us at this point:

On the Virginia side the ford road runs along the lower extremity of a high bluff off into the country, and another extends along the foot of the bluff, between it and the river, in the direction of Shepherdstown.

The bluff rises precipitously, is almost perpendicular, and is dotted with boulders and a stunted growth of timber. The roadway, a short distance from the Ford, passes a gap or ravine, obstructed and concealed by underbrush and passable with difficulty. Two gate-posts marked its entrance, indicating it as an abandoned private lane. From the ravine, a path led up to the high table-land above. Along the face of the bluff, near the glen, were several kilns or arches, used for the burning of lime. The river road passes over the kilns, the bluff still, as it passes over them, continuing to rise precipitately. Another road passes down from the bluff around and in front of the kilns.

The dam-breast, some ten feet wide, had been long neglected, many of the planks had rotted away or been removed, and water trickled through numerous crevices. The outer face, sloping to its base, was covered with a slippery green slime…

The base of the bluffs

Tom relayed that, when facing these bluffs, Captain Donaldson of Company H of the 118th felt an unpleasant similarity with the situation he’d seen just under a year before:

During all this time I felt very uneasy at the apparent want of caution displayed by our commander, and remarked to Lieut. Crocker, who happened near, that the place called vividly to mind Balls Bluff …

So steep is the terrain here, immediately opposite the ford, that the men of the 118th hiked upstream (west) along the River Road about a quarter mile to a ravine through which they climbed to the top of the bluffs. We chose a slightly easier path through a gully down the road about 200 yards the other direction.

Not in service in 1862, the mill began operating in 1829, supplying cement to nearby business and structures, and to the growing city of Washington by way of the C&O Canal across the Potomac. The dam earlier mentioned was built across the river to supply water to the mill wheel.

The newer brick arches to the left in the photo are post-War, but those to the right behind Larry Freiheit were here in 1862. We’ll hear of these again.

Up from the river, passing the Mill ruins

Pausing at another, larger kiln near the top of the bluff

Kiln from the top: loading hole

The apparent motion in this picture caused by the photographer moving backwards as the shutter opened. From here, about 20 feet above the kiln opening seen in the previous picture, you can see where limestone was loaded above the fire.

Continuing our climb over the crest, we came out onto a patch of ground likely part of the line held by Barnes’ Brigade – including the 118th Pennsylvania – between 10am and noon on the 20th. This position was about 400 yards from the Osborn farmhouse, and something over a mile from where Lovell’s US Regulars first made contact with the Brigades of A.P. Hill’s Division deploying along the Trough Road.

This was a good place to review the damp map Ed had kindly provided (ok, so it was dry when I got it), one in a series he developed to describe the action of 19 and 20 September.

We then hiked in along the Trough Road toward the Osborn Farm. Along the way passing two tracts of land preserved from future development by easements placed by their current owners. What great signs these are to see!

We came up the farm lane through the corn to the original Osborn farmhouse, having walked at least the edge of the heart of the battlefield. Also the heart of a developer’s dream of planting 152 houses there.

Hikers and barns

Although they look right, I don’t know if these barns were here in 1862. The house was, though. Apparently restored recently, it boasts an embedded iron ball. Also a recent replacement, it marks the spot where a 12-pound ball from a Federal gun across the river struck the house.

Osborn Farmhouse (click for close-up)

Now that we’ve walked the ground, here’s how the historians in the 118th Pennsylvania remembered that fateful day:

… An early breakfast was interrupted by orders to move. The meal completed, the brigade started in the direction of the river. With a few hurried personal preparations, some of the men removing their shoes and stockings, the column at 9 A. M. began the passage of the stream at Blackford’s Ford. There was a good deal of pleasant shouting as the troops splashed through the stream, and roars of laughter greeted those who, less fortunate than their fellows, stumbled and fell headlong into the water.

Just before the head of the column entered the ford, a brigade of Sykes’s regulars appeared upon the thither side, marching back again from the same reconnaissance with which Barnes’s movement was intended to generally co-operate. The columns passed each other midway in the river. The regulars gave the information that there was “no enemy in sight.” It was evidently twittingly said to encourage the volunteers, whom they held in no very high esteem, for at that time their rear skirmishers were actually engaged.

Though it was clear that the situation was a grave one, yet the 118th Pennsylvania was permitted to mount the cliff with its front entirely uncovered. No skirmish-line protected its advance until its right company was detached, and when it was deployed the enemy were pressing so hard that its deployment answered no purpose …

The brigade took the road that followed the base of the bluffs; and, as the head of the regiment approached the ravine or glen which led to the summit, a staff-officer dashed up hurriedly to Colonel Barnes, who rode at the time beside Colonel Prevost, and reported the enemy approaching in heavy force. Some vigorous action being instantly necessary, turning to Colonel Prevost, Colonel Barnes said: ” Can you get your regiment on the top of the cliff?” ” I will try, sir,” was the prompt reply, and dismounting, he conducted the head of his column into the narrow, unfrequented path that led through the glen…

From the top of the bluff it was open country for a mile or more, with occasional cornfields; then the fields changed to forest, and a wide belt of timber skirted the open lands. Farmhouse, barn and hay-stack dotted the plain, and to the right in the distance were the roofs and spires of Shepherdstown.

The report of the staff-officer that the enemy were approaching in force met with ocular confirmation. In front of the timber the musket-barrels of a division, massed in battalion columns, gleamed and glistened in the sunlight. To the right, not half a mile away, a whole brigade was sweeping down with steady tread, its skirmishers, well in advance, moving with firm front; and ere the head of the regimental column had scarce appeared upon the bluff, they opened a desultory, straggling fire … At this point Lieutenant Davis, the acting assistant adjutant-general of the brigade, on his way to the right to withdraw other regiments specially assigned to him to retire, observing that the 118th was making no movement to withdraw, but actually becoming engaged, called up the ravine to Lieutenant Kelly, the officer nearest him, to ” tell Colonel Prevost, Colonel Barnes directs that he withdraw his regiment at once.” … I do not receive orders in that way,” was the colonel’s sharp reply; “if Colonel Barnes has any order to give me, let his aide come to me,” and he continued to conduct the formation …

From the beginning the fire of the enemy was tremendous; the rush of bullets was like a whirlwind. The slaughter was appalling ; men dropped by the dozens … About this time it became lamentably apparent that the muskets were in no fit condition for battle. The Enfield rifle, with which the regiment was originally armed, was at its best a most defective weapon, and of a decidedly unreliable pattern. Some of the weapons were too weak to explode the cap. This defect was at first unnoticed in the excitement ; cartridge after cartridge was rammed into the barrel under the belief that each had been discharged, until they nearly filled the piece to the muzzle. A few charged cartridge with the bullet down and exploded cap after cap in a vain attempt to fire …

The enemy had now succeeded in pressing as close to the front as fifty yards, and the hot fire at such close range was increasing the casualties with frightful fatality. At the same moment he succeeded in developing a regiment across the ravine, completely covering the entire right. The two right companies, under the immediate supervision of the colonel, promptly changed direction by the right flank and gallantly checked the manoeuvre. This movement, mistaken by the hard-pressed centre for a withdrawal, induced it to break temporarily, and with the colors in the advance move in some disorder to the rear. Colonel Prevost caught the disorder in time to promptly check it. Heroically seizing the standard from the hands of the color-sergeant and waving it defiantly, he brought the centre back again to the conflict and completely restored the alignment. He was still waving the flag in defiance at the enemy when a musket-ball shattered his shoulder-blade and he was borne to the rear …

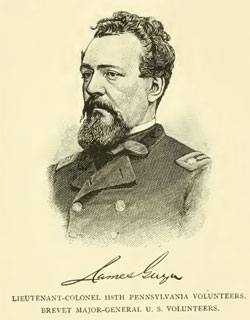

Just as [Lt] Colonel Gwyn assumed the direction of the fight, a rout was imminent. To steady the line and strengthen its weakening confidence, he gave the orders to fix bayonets … The officers were untiring and persistent in their efforts to hold their men together. At this critical moment, Captain Courtland Saunders and Lieutenant J. Mora Moss were instantly killed, the former with a musket-ball through the head, and the latter with one through the heart. Here, too, Captain Ricketts fell while in the act of discharging his pistol …

The order to retire, which, with the thickening disasters, had been long hoped for, came at last. The welcome direction, communicated through the loud voice of Adjutant James P. Perot, was repeated hurriedly all along the line. The scene that followed almost beggars description. The brave men who had contended so manfully against these frightful odds broke in broke in wild confusion for the river. Perot, unable from an injury in early life to keep pace with the rapidly retiring soldiers, remained almost alone upon the bluff. True to the instincts of a genuine courage, he stood erect facing the foe, with his pistol resting on his left forearm, emptying it rapidly of all the loads he had left, when he was severely wounded and ultimately fell into the hands of the enemy…

The greater part of the regiment made furiously for the ravine, down which they dashed precipitately. Since the march up, a tree, in a way never accounted for, had fallen across the path. This materially obstructed the retreat. Over and under it the now thoroughly demoralized crowd jostled and pushed each other, whilst, meanwhile, the enemy, having reached the edge of the bluff, poured upon them a fatal and disastrous plunging fire. The slaughter was fearful; men were shot as they climbed over the tree, and their bodies suspended from the branches were afterwards plainly visible from the other side of the river.

Others, who avoided the route by the ravine, driven headlong over the bluff, were seriously injured or killed outright. Among these was Captain Courtney O’Callaghan, who, badly disabled, was never again fitted for active field-service.

An old abandoned mill stood upon the ford road, at the base of the cliff. It completely commanded the ford and the dam-breast. When the last of the fugitives had disappeared from the bluff, the enemy crowded the doors, windows and roof and poured their relentless, persecuting fire upon those who had taken to the water …

In the midst of the rout and confusion the colors had been borne to the water’s edge near the dam-breast … Major Herring was opportunely at hand. He seized the staff and placing it in the custody of Private William Hummell, of D, directed him to enter the stream. Covering the soldier’s body with his own, with the color unfurled and waving with daring taunt, as if defying the enemy to attempt its capture, he successfully made the Maryland shore…

At this moment a battery from the Maryland side opened heavily. The practice was shameful. The fuses, too short, sent the terrible missiles into the disorganized mass fleeing in disorder before the serious punishment of the enemy’s musketry. It was a painful ordeal, to be met in their effort to escape an impending peril by another equally terrible. Shell after shell, as if directly aimed, went thundering into the [kiln] arches, bursting and tearing to pieces ten or twelve of those who had crowded there for cover…

One of the saddest incidents of this disastrous day happened after the action was really over. Lieutenant J. Rudhall White had passed through the desperate dangers of the contest and had safely landed upon the Maryland shore. As he reached the top of the river-bank he stopped and said: ” Thank God! I am over at last.” His halt attracted attention and a musketball, doubtless directly aimed from the other side by an experienced marksman, ploughed through his bowels. The wound was almost instantly fatal; he died as he was being borne away. White was a handsome, soldierly young man of scarce twenty summers. A native of Warrenton, Virginia, at the breaking out of the war he was a young lieutenant in the Black Horse Cavalry, a command subsequently famous in all the campaigns of Virginia. Differing in sentiments from his friends and his family, sacrificing the ties of home and friendship, he determined to defend his convictions with his sword…

________________

Notes

The Regimental History of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers is online both from GoogleBooks (1905 ed.) and the Internet Archives (1888); the former Corporal John L. Smith, publisher and editor. Those volumes contain the period narrative accounts and illustrations above. There’s also a lovely regimental roster in the back, and a set of biographical sketches. Here are some for the men of the regiment mentioned above:

Charles Mallet Prevost, Colonel of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Brevet Brigadier-General U. S. Volunteers and Major-General of the National Guard of Pennsylvania, was born in Baltimore, September 19, 1818. His paternal descent was from an old Huguenot family which was compelled to leave France upon the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and took up its abode in Switzerland, and from that descended the Sir George Prevost who commanded the British forces in Canada, and also the American branch. General Augustin Prevost, Sir George’s father, distinguished himself at Savannah during the revolutionary war. General Prevost from youth manifested a deep interest in everything pertaining to military life. For several years he was on the staff of his father, General A. M. Prevost, of Philadelphia. Upon the breaking out of the rebellion he assisted in the formation of the Gray Reserves, taking the position of Captain of Company C. He was subsequently appointed Assistant Adjutant-General of Volunteers on the staff of General Frank E. Patterson, and served through the Peninsula campaign, participating in the battles of Yorktown, Williamsburgand the seven days’ battle, down to Harrison’s Landing, whence, prostrated by the fever then prevailing, he was ordered home. During his convalescence he was selected by the Corn Exchange to command the 118th Regiment, which was being recruited. In the disastrous fight in which the 118th was engaged at Shepherdstown he received a terrible wound from which he never recovered. He rejoined his regiment and served through the Chancellorsville campaign, but was compelled to leave soon after. He was then commissioned Colonel of the 16th Regiment Veteran Reserve Corps, and had charge of the Confederate prisoners at Elmira, New York, and subsequently of a large rendezvous camp at Springfield, Illinois. He was honorably discharged June 30, 1865, and received the brevet of Brigadier-General United States Volunteers. After the war he was appointed to the command of the First Division, National Guard of Pennsylvania, with the rank of Major-General. He died November 5, 1887, as the result of his wound, having been for some time previous to his death partially paralyzed and deprived of his sight. His heroic endurance of suffering excited the love and admiration of his friends.

Brevet Major-General James Gwyn was born in Ireland, at Londonderry, November 24, 1828. His parents were Protestants and he received a liberal education at Foyle College, and emigrated to the United States, selecting Philadelphia for his residence. Here he entered the employ of Stuart Bros., of which George H. Stuart, famous during the war as President of the Christian Commission, was senior member. In April, 1861, he served as Captain in 23d Pennsylvania Regiment on the Peninsula and in front of Richmond. July 22, 1862, he resigned to accept commission as Lieutenant-Colonel of the Corn Exchange. He was mustered into service with this regiment as Lieutenant-Colonel, August 16, 1862. He participated in its first engagement at Shepherdstown, Virginia, where the regiment fell into an ambuscade and was fearfully decimated; he also participated in the battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. At the close of these campaigns he was promoted to Colonel of the regiment, November 1, 1863, having succeeded Colonel Charles M. Prevost, who had been seriously wounded at Shepherdstown, September 20, 1862, and resigned, September 30, 1863. May 5, 1864, in the first day’s fight in the Battle of the Wilderness, he was severely wounded in the right thigh. He rejoined his regiment in front of Petersburg, Virginia. At Peeble’s Farm, September 30, 1864, Colonel Gwyn as senior officer commanded the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, 5th Army Corps. He led forward his men with gallantry and captured two earthworks and a fortified line, and for this meritorious behavior he was breveted a Brigadier-General. At Five Forks, April 1, 1865, in the famous charge, General Gwyn’s brigade captured a large number of prisoners and many battle-flags, and as a reward he was promoted to the rank of Brevet Major-General. At the close of the war he was mustered out of service with the regiment, June 1, 1865. He then returned to mercantile pursuits with his old employers, Stuart Bros., but after a time, failing in health, he retired and is now [1888] in the Soldiers’ Home at Hampton, Virginia. Brevet Major-General James Gwyn enjoyed the reputation of having been a patriotic citizen, a gallant soldier, a handsome and accomplished officer, and a bold and aggressive leader. He was by nature impulsive and sometimes revengeful, with likes and dislikes, characteristic of his race, strong and exacting. These traits won him many warm friends, and at the same time made him many bitter enemies in the regiment.

Charles P. Herring, Colonel of the 118th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers and Brevet Brigadier-General, was born in the city of Philadelphia. Until the opening of the rebellion he was engaged in mercantile pursuits. In June, 1861, he became Second Lieutenant of Company C of the Gray Reserves, commanded by Captain Charles M. Prevost. In May, 1862, he acted as Adjutant of the battalion under Colonel Charles S. Smith in its service in quelling the Schuylkill county riots. In August, 1862, he was commissioned Major of the 118th Regiment and commanded the camp for recruits in Indian Queen Lane, near the Falls of the Schuylkill. After recovering from the wounds which terminated in the loss of a leg at Dabney’s Mills, February 6, 1865, he sat upon a general courtmartial convened in Philadelphia, and soon after his muster out of the service in June, 1865, was appointed Brigade Inspector of the National Guard, in which capacity he was influential in resolutely maintaining a high standard of excellence. In a remarkable degree he had the confidence and friendship not only of his own command but of his superior officers. General Barnes, in allusion to his loss of a limb, said: “You bear with you the evidence of the peril of the field. This gives me no cause for surprise; for I had seen you at Shepherdstown, at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg.” “Gallant and ever reliable as an officer,” says that bold soldier, General Griffin, “he was humane and considerate towards those under him, always being solicitous for their welfare. On the field of battle, or in camp, his manly bearing won for him the friendship of all. His record is one that he not only should feel proud of, but his State should prize as belonging to one of her sons.” “With a moral courage,” says Major-General Chamberlain, late Governor of Maine, who served with him, “scarcely excelled by his physical daring, he won and held my perfect confidence and love.”

Captain Francis Adams Donaldson was born in Philadelphia, June 7, 1840. He was enrolled as a sergeant of the 71st Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers (Baker’s California Regiment), May 26, 1861, and was mustered into the service June 4, 1861. He was taken prisoner at Ball’s Bluff, October, 1861. His conspicuous gallantry in this engagement was rewarded by promotion to a second lieutenancy, May 1, 1862. He was severely wounded at Fair Oaks, May 30, 1862. Upon his recovery he was mustered out to accept the captaincy of Company H, 118th. He was honorably discharged, January 14, 1864.

Donaldson’s wartime correspondence was published in Inside the Army of the Potomac (1998).

Captain Joseph Wattson Ricketts was born January 16, 1836, in Baltimore, Md. He was educated at the Military Academy at Sing Sing, N. Y. ; was a member of the 1st Regiment National Guard of Pennsylvania. He recruited Company K and was its captain. He was killed at Shepherdstown, Va., September 20, 1862. The captain had a presentiment of his death just before crossing the Potomac on the morning of the battle. He called a few of his friends around him and said, “The regiment will soon be in battle, and I shall not live to recross the river, for I certainly shall be killed.” He requested that his effects be looked after in just as cool a manner as if at home dictating his will. His death occurred precisely as he had previously described.

Adjutant James P. Perot was born in Philadelphia, May 12, 1825. His parents were members of the Society of Friends, and he graduated from Haverford College. He became associated with Mr. Christian J. Hoffman in the flour and grain commission business, and at the breaking out of the civil war he was one of the originators of the Philadelphia Corn Exchange. He was active in the formation by that body of the 118th, and accepted the position of adjutant. He died in 1872. Colonel Perot, or, as he will always be spoken of by his associates of the 118th, Adjutant Perot, was a patriotic man, a faithful, courageous soldier, and by his genial disposition won many friends.

Joseph Mora Moss, who came of good old revolutionary stock, being directly descended from both Robert Morris, the financier, and Bishop White, the first Bishop of Pennsylvania, was born in Albany township, Bradford county, Pennsylvania, May 17, 1843. He was educated in the public and High School of Philadelphia. At the breaking out of the war he was about to begin his studies with a view of preparing himself to enter the ministry of the Protestant Episcopal Church. Considering it his duty to his country, he

promptly answered the call to arms, and was enlisted as second lieutenant in the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers. He was killed in battle at Shepherdstown, Virginia, September 20, 1862, and was at the time of his death nineteen years four months and three days old. He was prompt in the performance of his duties, and won the respect of his superiors. His early death on the field cut short a career that doubtless would have been a brilliant one.

Lieutenant J. Rudhall White, born in Warrington, Virginia, was about twenty years of age when he joined the regiment. He was a lieutenant in the Black-Horse Cavalry (Confederate). Differing in sentiment with his friends, he resigned his commission and entered the 118th as second lieutenant. He was a brave and courteous officer and gained the respect of the regiment. He was killed at Shepherdstown.

After Captain Courtland Saunders’ (Co. G) death, his father donated land and money for the Presbyterian Hospital in West Philadelphia, still in service. Saunders was 21 years old when he was killed. From privilege and wealth, he had been a teacher and author of a Latin textbook before the War.

_______________

Thanks

A big thank you to my fellow waders: in addition to enjoying excellent tramping companions, I was glad to be part of a number of stimulating conversations debating conservation, history, and how it all may have happened 146 years ago.

Thanks especially to Ed and Carol Dunleavy, Mike Nickerson, and the other SPCA members who shuttled us to the Ford, watched over us in the river and out, obtained the permissions we needed to ramble about on private property, and provided the superior beverages and victuals after the hike. I was honored to have been a part.

And again, to Dr Tom Clemens for leading the walk and bringing the history alive.

October 5th, 2008 at 5:03 pm

Brian,

An excellent writeup and photos! It was a treat for us all to be there. Perhaps Tom can make this adventure an annual affair.

Larry F.

October 5th, 2008 at 10:30 pm

Brian,

Your post announcing this addition is too modest, you’ve done a wonderful job here. Bravo. Not sure about an annual event, maybe. Right now we’re gearing up for the Vince Armstrong dinner and walking tours Saturday.

October 6th, 2008 at 9:36 am

Brian,

Great photos and a well written summary of the events. Wish I could have attended, but events kept me high and dry that week.

Craig.

October 6th, 2008 at 11:35 am

Brian,

Fantastic post, looks like it was a great time. Thanks for posting it.

Don

October 7th, 2008 at 9:52 am

Thank you Larry, Tom, Craig and Don! You all know how much difference treading the actual ground makes in trying to grok the history. I’m very glad to have been there – it proved a priceless day for me.

October 21st, 2008 at 9:10 pm

As an added touch, here’s the link for the regiment’s history — pretty good reading. http://books.google.com/books?id=pxlCAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=regiment+history&as_brr=1

December 4th, 2008 at 12:06 am

a very good article, well wrote with some good pictures.

Wish i could have been there.

June 29th, 2009 at 3:08 pm

I was wondering if James Wills name shows up in the Roster for the 118th PA. He was my great, great uncle and I am interested in any info on him. Thank You.

July 9th, 2010 at 10:09 pm

Great post…i enjoyed reading it…i’ll have to make that trip some day…my great, great grandfather was Wm McClintock who served throughout the war in Co. G…we’ve already traced the 118th’s movements at Gettysburg and Northern Va…thanks again.

January 12th, 2012 at 10:05 am

I would have enjoyed doing this with your group so I could know what it felt like for my 2nd Great Grandfather CPL William McLachlan, E Co., 118th Regt. who was subsequently captured and held at Winchester. Will you be doing this again this year on the 150th anniversary?