Totally useless as an officer

3 February 2025

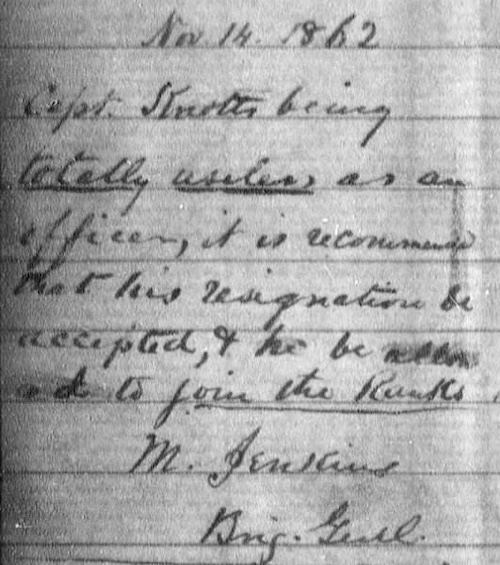

Bold language is rare in military communications, so I thought I’d share this instance so both of my readers can enjoy it with me. It’s a clipping from the back of Captain Joseph E Knotts‘ letter of resignation of 14 November 1862. Knotts was Captain of Company K of the First (Hagood’s) South Carolina Infantry.

[touch the image to see the whole sheet]

The back of the letter includes the signatures of Knott’s higher chain of command – brigade commander Micah Jenkins (excerpted above); George Pickett, division; James Longstreet, army corps; and (I think) Robert Chilton, AA&IG on behalf of Robert E Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia.

General Jenkins’ comment here hints at poor leadership in the regiment more generally during and after the Maryland Campaign – that of all three field officers (Col. Duncan, Lt. Col. Livingston, Maj. Grimes) and at least two of the senior Captains (Knotts and Stafford, Co. I).

Jenkins was not in Maryland on the Campaign, he’d been wounded at 2nd Manassas in August, and his brigade was commanded by senior colonel Joseph Walker of the Palmetto Sharpshooters. In his after-action report of 24 October 1862, Walker noted:

I regret, however, to be called upon again to refer to the conduct of a large portion of the officers and privates of the First Regiment South Carolina Volunteers in this battle in terms of censure. The commanding officer reports that the regiment entered the fight with 106 men, rank and file, lost 40 men killed and wounded, and at the close of the day but 15 enlisted men and 1 commissioned officer answered to their names. Such officers are a disgrace to the service and unworthy to wear a sword …

For more, see the regiment’s page and officers’ capsule bios over on AotW.

For a deeper dive, I recommend James R Hagood’s Memoirs of the First South Carolina Regiment of Volunteer Infantry … an unpublished manuscript he wrote shortly before his death in 1870. It’s online and downloadable [17MB pdf] from the University of South Carolina. JR Hagood was Sergeant Major and acting Adjutant of the regiment at Sharpsburg in 1862 and was appointed Colonel in November 1863 over half a dozen officers senior to him.

Notes

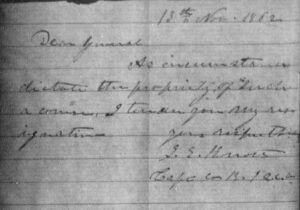

Knotts’ resignation letter is from his Compiled Service Records; I found it online from fold3 (subscription service). Here’s the useful part of the front of the page:

Brig. Gen. Jenkins’ comments transcribed:

Nov. 14, 1862

Capt. Knotts being totally useless as an officer, it is recommended that his resignation be accepted, & he be allowed to join the Ranks.

M. Jenkins

Brig. Genl.

Thanks to Jim Smith for locating Hagood’s manuscript, an excellent resource with details about the regiment, its officers, and individual casualties.

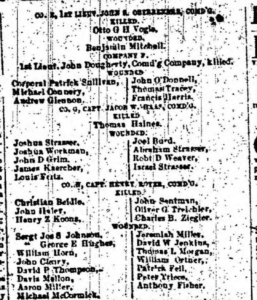

Crampton’s Gap casualty list, 96th Pennsylvania Infantry

31 August 2024

Appended to Colonel Cake’s official report as printed on page 2 of the Pottsville (PA) Miner’s Journal of Saturday, 4 October 1862, is his list of the men of his 96th Pennsylvania Infantry who were killed or wounded in the fight at Crampton’s Gap on South Mountain on 14 September 1862. It’s not found in the Official Records in company with the Colonel’s report.

My transcription of the text and links to the individual soldiers’ pages on AotW, after the jump …

Maryes in Maryland

8 April 2024

Here’s Lieutenant Edward A. Marye‘s (probably pronounced “Mary”) family home in Fredericksburg, VA as it looked in May 1864, then in use as a Union military hospital for troops wounded during the battle of the Wilderness.

First Lieutenant E.A. Marye (1862)

His father John Lawrence Marye (1798-1868), a successful lawyer and mill owner, bought land and a small house on a hill overlooking Fredericksburg in about 1824. He improved the house and named it Brompton, after the Middlesex village in England from which his Hugenot-Norman great-grandfather Rev. James Marye (or Jacques Marie, 1692-1768) came to America in about 1730.

The high ground around it became known as Marye’s Heights – now famous for the combat there in December 1862.

Lt. Edward Marye commanded a section of 2 3-inch Ordnance rifles of the Fredericksburg Artillery (Brig. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Division) at Harpers Ferry (14-16 September) and Shepherdstown (19 September), and led the battery at least part of the day at Sharpsburg (17 September) while Captain Carter M Braxton acted as Hill’s chief of artillery.

But there were also 4 other Maryes in the battery …

Private Alfred James Marye, Edward’s nephew, was on the Maryland Campaign and was wounded by counter-battery fire at Boteler’s Ford on the Potomac on 19 September. He was barely 16 years old. He served with the battery to the end of the war and was afterward a railroad clerk in Montgomery County, VA.

Private Alexander Stuart Marye (1841-1915), a younger brother of Edward’s, enlisted in the battery in June 1862 and was probably in Maryland in September. He was on detail away from his unit on ordnance and administrative duties for most of the rest of the war and was surrendered and paroled at Greensboro, NC in May 1865.

John Lawrence Marye, Jr. (1823-1902), also Edward’s brother, enlisted as a Private in April 1861 and was promoted to 5th Sergeant in April 1862. He was absent, sick into October 1862, so probably not in Maryland, but was surrendered and paroled with the battery at Appomattox Court House, VA on 9 April 1865. During the war he also served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1863-65). He’d been a wealthy lawyer and farmer in his own right before the war, and Mayor of Fredericksburg in 1853-54. He was afterward again a Delegate (to 1868) and Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1870-74).

Another of Edward’s nephews, his oldest brother James’ son Private William Nelson Marye (1841-1929) enlisted in Braxton’s Mounted Artillery (later Fredericksburg Light) on 12 May 1861, but was detached from his unit for much of 1862 and probably not with them in Maryland. He was with the battery from March 1863 to September 1864, when he was again detailed, as a clerk to a military court for the 3rd Army Corps, but was back by Appomattox in April 1865.

To complete Edward’s story: he was promoted to Captain and it became his battery in March 1863, but he did not survive the war; he died of disease in Petersburg, VA in October 1864.

Notes

The photograph above of the Marye house “Brompton” is from the Library of Congress.

Details about Brompton from its National Register of Historic Places nomination form [pdf]. The home was acquired by Mary Washington College (now University) in 1947 and it is now their president’s residence.

Lieutenant Edward Marye’s picture here is an ambrotype in the collection of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond.

The Maryes’ military records are found in the US War Department’s Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers, Record Group No. 109, Washington DC: US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).