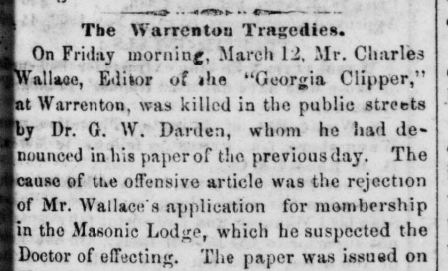

The Warrenton Tragedies (1869)

6 February 2026

Charles Wallace was the son of a prominent Atlanta businessman and politician, and first enlisted for war service in May 1861 with the First Georgia Infantry at age 17. When they were disbanded in early 1862 he enlisted again, as a trooper in Cobb’s Legion Cavalry Battalion. He was wounded in Maryland that September (probably at Quebec Schoolhouse) and sent home to recover. By the end of 1863 he was First Lieutenant of Company D of the 2nd Regiment, Confederate States Engineers and served with them to their surrender in May 1865.

The sad story of his death at just 25 years old is seen in the clipping above, from the 19 March 1869 edition of the Georgia Enterprise of Covington, GA.

At least one other newspaper account added a political dimension, suggesting that Wallace’s Clipper was a Ku Klux Klan paper and Wallace was a Democrat, and that Dr George Washington Darden (b. 1825) was a “highly respectable and wealthy citizen and well known loyalist” and supposed Republican, and that the mob of men who killed Dr Darden were KKK members.

Questions. Questions.

27 January 2026

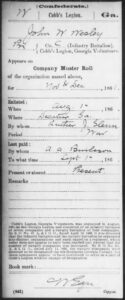

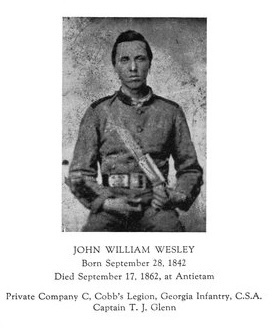

Not-quite 19 year old farm boy John W Wesley enlisted at Decatur in DeKalb County, GA on 1 August 1861 and mustered on 5 August as a Private in Captain Luther Glenn’s Stephens Rifles – Company C of Cobb’s Legion Infantry Battalion. He was marked as present for the period of November and December 1861 on the Company muster roll, the only direct record of his service.

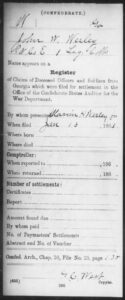

On 13 January 1863, sometime after his death, his father Marvin filed a claim with the Confederate government for his final pay.

Between December 1861 and January 1863 his life is a mystery to me.

Family history says he was killed in the Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg on 17 September 1862, but this is unlikely, given that he was buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, VA. As far as I know, no soldier’s remains were ever removed from the battlefield for burial in Richmond. He could have been mortally wounded there (or at Crampton’s Gap on 14 September) and sent to a hospital in Richmond, dying later.

Unfortunately there are no records about this in his Compiled Service Record folder.

His grave marker in Hollywood has his death as 13 January 1862.

I do not know where that date came from. It could be that he died of disease or other non-combat cause in a Richmond hospital on that date, though I’d expect in that case the December 1861 muster roll to have him absent in hospital at the end of 1861. I’d also expect his father would have claimed earlier.

It could be a simple error, that he died on 13 January 1863 (not 1862), but that seems oddly coincidental with the date his father filed.

It could also be that the man under that stone is not our soldier at all.

Family history also indicates John was a frequent letter writer, so they probably would have noted it if the letters stopped by January 1862. Though they do not give the dates of his letters.

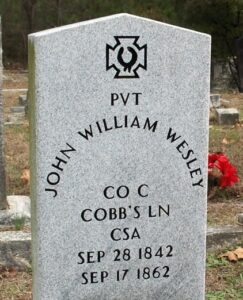

He also has a modern government marker in his hometown of Lithonia, GA, requested by a well meaning person who seems to have taken the family lore about his death as fact.

I hope to learn more about John William Wesley and determine how he met his end – whether as a result of service in the Maryland Campaign of 1862, or otherwise. But for the moment all I have are questions.

Notes

His picture at the top is a page from Bruce, Wesley, & Cottingham’s Ancestors and Descendants of Marvin Hammond Wesley and Mary McClung (2000).

The grave marker photographs are by George Seitz and the late user Bud, respectively, online from Findagrave.

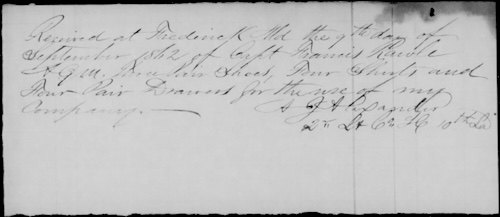

Receipt for shoes, shirts, and drawers (1862)

7 January 2026

At Frederick, MD on 9 September 1862 Adam J. Alexander of the 10th Louisiana Infantry signed this receipt for 3 pairs of shoes, 4 shirts, and 4 pairs of drawers for his men. It is likely these had been procured in the city from local businesses by Confederate quartermasters.

There are a number of interesting things about this document, beyond the fact that it shows distribution of stores in Maryland probably bought with Confederate scrip – which would have been largely worthless to Fredrick merchants.

First: He was born Adam J Alexandre to a well-off butcher in St. John the Baptist Parish in about 1841. His signature says that by 1862 he was spelling his last name “Alexander.”

Second: he gives his rank as 2nd Lieutenant, though his service record says he had been promoted to Captain sometime earlier. Clearly he had not received word by the 9th of September.

Third: Young Captain Alexander was killed in action at Sharpsburg, MD just over a week after signing this receipt.

Notes

The receipt is from Capt. Alexander’s Compiled Service Records (CSRs) in the National Archives. This copy online from fold3.

The other name on that receipt is that of his regimental Quartermaster, Captain Francis Rawle.