Just as surely dead

8 October 2012

Arthur F. Hascall, (c, 1861, NY State Military Museum)

I’m scrubbing through unit rosters, regimental histories, and many other documents as part of the Antietam Roster Project. Most of the listings are sketchy and dry, and when I have the chance, I like to dig a little deeper for more information to flesh out the individuals who were at Antietam.

An example of how this sometimes goes, with a bit of an unexpected twist, is the case of Sergeant Arthur Hascall of the 61st New York Infantry.

It started for me with the entry for him in the History of Antietam National Cemetery which lists burials for at least 1250 Union soldiers who were casualties of the 1862 Maryland Campaign.

| Sec | Lot | Grave | Rank |

Name |

Co | Regt | Service | Death |

Remarks |

| 25 | C | 333 | Sergeant, | Hascall, Arthur Foot | E | 61 | Infantry | Nov. 11, 1862 | Smoketown |

Fairly basic, but a good start. I began to look more systematically at his Regiment, the 61st New York Infantry, using the New York State Adjutant-General’s report. It was published in 1901, and has at least minimal service information for nearly every soldier ever in the unit. Not perfect, but better. It got me this:

Service data for Arthur and his younger brother Ralph, who enlisted with him and was killed at Malvern Hill.

When I googled the brothers, I found a 2002 article in the Colgate University magazine. Ralph and Arthur were grandsons of Daniel Hascall, a founder of the Baptist seminary that later became Colgate. Both young men were reported to be buried in the tiny cemetery at the university.

If Arthur is buried in Hamilton, New York, he’s not at the National Cemetery. So now I’m not sure either way.

Google also found me the striking photograph at the top of this page. I think there’s a whole ‘nother post just on the circumstances under which that one and maybe a thousand other soldier’s pictures were nailed to the walls of the New York State Capitol in Albany.

So far, it looks like Arthur died of wounds received at Antietam. That’s the record from the AG, and that’s what his family put on his stone.

But that’s not exactly what happened to Arthur. He died of an injury received at Antietam, all right, but it was caused by a soldier in his unit, and probably an accident. I shouldn’t be surprised about this I suppose, but I’ve looked at thousands of soldiers killed or wounded at Antietam, and this is the first accidental death I’ve found.

The story is in a superb reference that is too frequently missed – The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion:

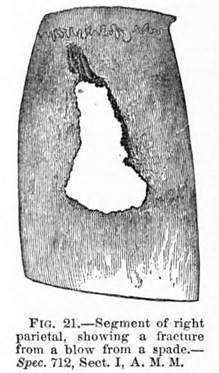

At Antietam, Maryland, September 17th, 1862, a soldier, employed in entrenching, struck another, on the left side of his head, with the edge of a spade. The wounded man fell, badly stunned, and, on examination, it was found that the blow had produced a depressed fracture of the left parietal bone. The patient was conveyed to the Smoketown Hospital, and was placed under the care of Surgeon B. A. Vanderkieft, U. S. V. He breathed with stertor, and had a slow pulse, dilated pupils, and the other signs of compression of the brain. The scalp was shaved, and an incision was made, through which a number of fragments of detached bone were removed. The patient lingered, in a state of stupor, until November 8th, 1862. The particulars of the case are not recorded in the register or in the reports from Smoketown Hospital; but the only death in the hospital from fracture of the cranium, at the date referred to, is that of Sergeant Arthur F. Hascall, Co. C, 61st New York Volunteers.

The fracture extends downwards from the sagittal suture three inches, and it is an inch wide at its lowest part. A few fragments are adherent to the inner table, and the edges of the orifice are carious. The specimen is represented in the adjoining wood-cut, (Fig. 21.) The contour of the aperture in the bone represents, with exactness, the outline of the edge of the spade. The specimen was forwarded to the Army Medical Museum by Surgeon Vanderkieft, by Hospital Steward A. Schafhirt, U. S. A. The latter states that a detailed history accompanied the specimen. A careful search has failed to discover this paper, and the registers of the Museum contain no indication of its reception.

The combined 61st and 64th Regiments, maybe 250 men total, were in the lead of General Richardson’s 1st Brigade (Caldwell’s), and came in behind and left of the Irish Brigade’s line in the attack on the Sunken Road position [map]. Colonel Barlow of the 61st brought them further left and got an enfilading angle on the Confederates in the Lane. It was probably that deadly fire – combined with some command confusion in the road – that finally broke the line.

It doesn’t seem likely anyone in the 61st would have been entrenching during their assault on the Sunken Road, but it might have been earlier. There are any number of other reasons a soldier would have been wielding a spade on that day.

Our Sergeant was just as dead, no matter the circumstances, as the thousands of others whose lives were taken by hostile fire in that terrible battle.

________________

Notes

Antietam National Cemetery, Board of Trustees, History of Antietam National Cemetery, Baltimore: John W. Woods, Steam Printer, 1869.

The Cemetery History is beautifully presented online by the Western Maryland Regional Library on their WHILBR site.

State of New York, Adjutant-General, Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of New York for 1900: Registers of the 58th, 59th, 60th, 61st, and 62nd Regiments of Infantry, 1 of 43 Volumes, Albany: James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1893-1905, Issue 26 (pub. 1901), pg. 939

Barnes, Joseph K., and US Army, Office of the Surgeon General, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 6 books, Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1870, Part. I, Vol. II, pg. 57

Hascall’s photograph in the collection of the NY State Military Museum, found online through the New York Heritage portal.

Photos of the Hascall Brothers’ stone at Colgate and Arthur’s at Antietam National Cemetery are available from Findagrave.

February 9th, 2013 at 1:28 am

I served in the US Air Force as a medic. The first thing that struck me when reading the surgeon’s report was that this injury was not “accidental”. A sergeant would not be entrenching w his troops-although he would pass down orders to the same. The site and force of the injury argues against “accidental”, and more like someone clobbering him as he walked away after giving orders-done by someone w/out any witnesses to testify against the perpetrator-or deliberate cover up of the truth by the bad actors. It happens in wars-coined “fragging” during Viet Nam. (see the movie Platoon) That was my immediate visceral reaction and one can only hope that if this was true, his murderer got his just reward later-if there is such a thing as justice in this world.

April 8th, 2013 at 6:04 am

[…] This is most interesting. […]

July 31st, 2013 at 10:38 pm

Arthur Foote Hascall was my 1st cousin 3x removed. His mother Angeline Storm Hascall was my 2nd great grand aunt. Angeline and her husband James Hascall appear to have separated by 1860 and I don’t believe ever divorced. She lived with Daniel Skinner for 30 years, until her death. What is interesting here is Daniel also served in the 61st, Sergeant, Co C and was discharged on Nov. 11, 1862 the same day Arthur died.I don’t think that is a coincidence. It says he was discharged due to aggravating a previous shoulder wound. Daniel’s photo is also on the same site as Arthur’s.

October 23rd, 2013 at 10:26 am

Excellent research!