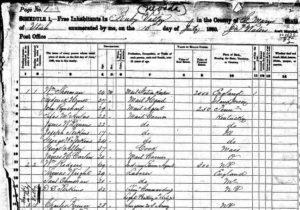

Battery B, 4th US Artillery in July 1860

10 March 2022

In 1860, the companies [of the 4th United States Artillery] in Utah were kept busy protecting the parties of emigrants going West, and keeping open the mail routes. Light Battery B, operating as cavalry, marched during that summer 2000 miles over a barren and desert country, and though the Indians were continually hostile, the roads were kept open. The battery had a successful fight against 200 Indians at Eagan’s Canyon, August 11, 1860, losing three men wounded (one mortally).

From May to October 1860 Battery B was based at the small Pony Express station located at Station Spring at the southern end of Ruby Valley in western Utah Territory (now Nevada). 32 year old First Lieutenant D.D. (Delavan Duane) Perkins, USMA ’49 was in command; Lieutenant Stephen H Weed USMA ’54 and Surgeon Charles Brewer (Assistant Surgeon CSA 1861-65) were the other officers.

On 15 and 16 July 1860 US Census enumerator J.P. Waters identified 105 Americans there, but did not include the band of Shoshone who lived nearby. His three page [ page 1 | page 2 | page 3 ] listing of the residents is a great reference for students of the Battery.

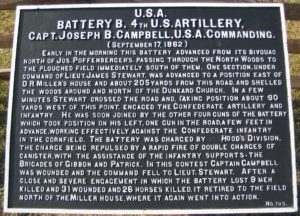

Among the 70 soldiers listed in Ruby Valley that summer at least 17 were also in action with Battery B just over two years later at Antietam, including then-Sergeant James Stewart, who commanded the Battery at Antietam after Captain Campbell was wounded, and Private Richard L Tea, who was slightly wounded at Antietam, was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1876 for action against the Cheyenne in Kansas the year before, and retired from the Army in 1888 after 30 years in uniform.

Others of the Battery in that 1860 Census list known to be at Antietam in 1862:

William West (WIA Antietam)

John Mitchell

Andrew J Ames (WIA Antietam)

Joseph Brownlee (WIA Antietam)

John Brown (KIA Antietam)

James Cahoo

Frederick A Chapin

Henry P Lyons (KIA Antietam)

William Kelly

Joseph Herzog (MWIA Antietam)

Andrew McBride

John Wilsee/Wilsey (WIA Antietam)

Robert Moore (WIA Antietam)

William Kelly

William Moffitt (WIA Antietam)

_______________

The quote at the top is from the US Army history of the 4th Regiment of Artillery, online thanks to the Center of Military History.

The census pages are from 1860 United States Federal Census, Population, Schedule 1. NARA microfilm publication M653 (1,438 rolls). Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. The Ruby Valley, St. Mary’s, Utah Territory set are on roll M653_1314, Pages 1-3. I found these page images online thanks to FamilySearch.

The photograph of the Battery’s battlefield tablet at Antietam was taken by Craig Swain for the HMDB.

Old Man Guest

21 February 2022

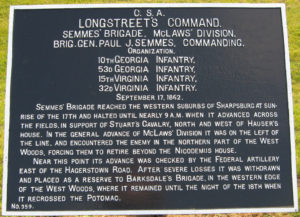

Benjamin Franklin Guest was at least 55 years old when he was killed in the battle at Sharpsburg in September 1862; a Private in Company F, 53rd Georgia Infantry.

His is indeed a hard-luck story.

Family history, supported by the US Census, says he lost his Madison County, GA farm and his family due to his drinking, and by 1860 was living alone, an overseer on a farm in Griffin, Spalding County, GA. In May 1862 he signed-up as a substitute for one R.A. McDonald (possibly Robert Alexander McDonald, 1831-1904) of Company F.

The family story says he was killed by a “sniper” on 16 September at Sharpsburg, which is somewhat unlikely, as the 53rd Georgia and the rest of the Brigade arrived at Sharpsburg from Harpers Ferry at sunrise on the 17th. His very brief military record says he was killed on 17 September.

I don’t have a birth year for every soldier killed at Sharpsburg, but among those I do have, Guest is the 2nd oldest. The oldest being Private Adam Burkel of the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry – who was about 57 years old at Antietam.

———————–

The photograph of Semmes’ Brigade’s battlefield tablet was taken by Craig Swain for the Historical Marker Database (HMDB).

Fighting them twice at Sharpsburg

19 December 2021

Private William F. Ford of the Tom Green Rifles, Company B, 4th Texas Infantry had an extraordinary war.

At Sharpsburg on 17 September 1862 he and his regiment were part of Hood’s Division’s devastating charge into Miller’s cornfield early that morning. But that wasn’t enough for Ford.

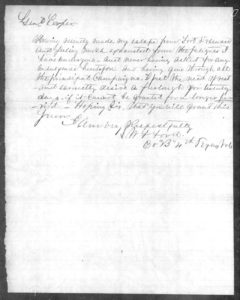

… after the Brigade was relieved about 10 o’clock am, he was sent off and accidentally meeting the 9th Georgia Regt. reported to Capt King of Co “K” and fought with them till night. Capt King gave him a certificate complimenting him for his gallant conduct thro’ the the day, which certificate was endorsed by both the Col commanding the 9th Georgia Regt and Col Anderson – now Brigadier – commanding the Brigade …

He was captured at Gettysburg in July 1863 and sent to the US prison at Fort Delaware. From which he escaped in August or early September. Not an easy thing, as shown by the fate of Hoxey Whiteside, Company G of the 4th Texas, who attempted such an escape a couple of months after Ford, in November 1863, but drowned in the Delaware River.

Private Ford “passed through parts of Delaware, New Jersey, and Maryland in the disguise of a citizen, arriving safely in Richmond” and, not a shy man, made a request for a furlough directly to the CSA’s Adjutant General, General Samuel Cooper – “hoping sir, that you will grant this favor.” Cooper did.

He was commissioned Junior 2nd Lieutenant of his Company on 1 April 1864 “for valor and skill” and distinguished himself in combat again, in the Wilderness of Virginia, where he was wounded in the leg on 6 May 1864. He was promoted to Senior 2nd Lieutenant on 16 June.

In addition to all this, his is the second case [first, here] I’ve found of a Confederate officer applying to raise and command a “negro regiment.”

He made that request on about 12 March 1865 through his military chain of command, and a week later wrote to John H Reagan, the Postmaster General of the Confederate States, asking for help in expediting it.

Reagan forward a positive recommendation to Secretary of War Breckenridge on 22 March. The reply came back the same day (cover below).

Res. ret’d to the Post Master General. The application has not reached us, but the Dept. has decided not to grant authority to recruit larger organizations of col’d troops than companies except where a battalion of four companies can be raised from one estate.

By com’d Sec. War:

[Captain] John W. Riely, AAG

Word got to Lieutenant Ford on 30 March 1865. It was largely a moot point by then, anyway – Federal troops entered Richmond 4 days later.

He was surrendered and paroled at Appomattox Court House, VA on 9 April 1865, and went home to Austin, Texas. He died there in 1875.