An English saddle in wartime Richmond

28 July 2025

Behold a receipt for an English Saddle & Equipments purchased by Sharpsburg veteran Major, soon to be Lieutenant Colonel Henry A Rogers of the 13th North Carolina Infantry in Richmond, VA in July 1863. It was $125.

For reference, due to wartime shortages and inflation, bacon cost $1.25/pound and flour was $28/barrel in Richmond, four times their pre-war prices. And his pay was $130/month for May and June 1863, while still a Captain. It would rise to $150/month as a Major and $170 as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Rogers’ saddle was probably made in the Ordnance Harness Shops at Clarksville, VA, but may instead have literally been English-made and came through the blockade from England.

The W.S. Downer seen on the receipt is Major William S Downer, Superintendent of Armories at the Richmond Arsenal, the organization responsible, among other things, for issuing horse equipment of all kinds. M S K = Military Storekeeper. Downer, by the way, had been a clerk at the US Army’s arsenal at Harpers Ferry, VA in 1860.

Here’s Henry Rogers at about the time of his purchase, in a portrait of unknown provenance from the Chancellorsville Vistor Center.

Notes

The receipt above is among Rogers’ Compiled Service Records, now in the National Archives. I got my copy from fold3, a subscription service.

The 13th Alabama Infantry in Maryland, in detail

19 July 2025

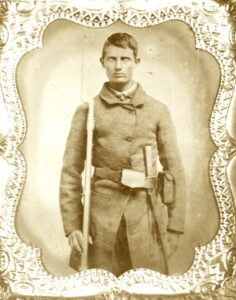

Private “Mage” Allen, Company H [Alabama Archives]

I’ve just completed a thorough scrub through the military and other records of the men of the 13th Alabama Infantry regiment, and extracted service and personal details for those who were present on the Maryland Campaign of September 1862.

Following is some interesting information that comes from that collection of data.

Totally useless as an officer

3 February 2025

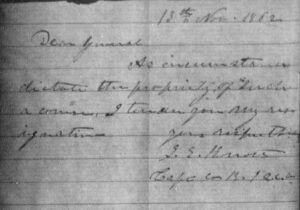

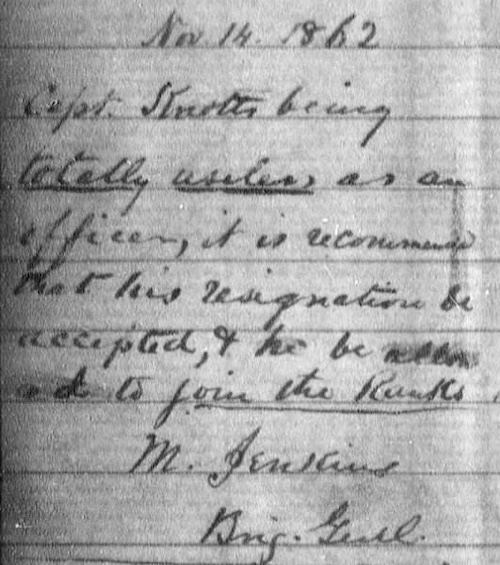

Bold language is rare in military communications, so I thought I’d share this instance so both of my readers can enjoy it with me. It’s a clipping from the back of Captain Joseph E Knotts‘ letter of resignation of 14 November 1862. Knotts was Captain of Company K of the First (Hagood’s) South Carolina Infantry.

[touch the image to see the whole sheet]

The back of the letter includes the signatures of Knott’s higher chain of command – brigade commander Micah Jenkins (excerpted above); George Pickett, division; James Longstreet, army corps; and (I think) Robert Chilton, AA&IG on behalf of Robert E Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia.

General Jenkins’ comment here hints at poor leadership in the regiment more generally during and after the Maryland Campaign – that of all three field officers (Col. Duncan, Lt. Col. Livingston, Maj. Grimes) and at least two of the senior Captains (Knotts and Stafford, Co. I).

Jenkins was not in Maryland on the Campaign, he’d been wounded at 2nd Manassas in August, and his brigade was commanded by senior colonel Joseph Walker of the Palmetto Sharpshooters. In his after-action report of 24 October 1862, Walker noted:

I regret, however, to be called upon again to refer to the conduct of a large portion of the officers and privates of the First Regiment South Carolina Volunteers in this battle in terms of censure. The commanding officer reports that the regiment entered the fight with 106 men, rank and file, lost 40 men killed and wounded, and at the close of the day but 15 enlisted men and 1 commissioned officer answered to their names. Such officers are a disgrace to the service and unworthy to wear a sword …

For more, see the regiment’s page and officers’ capsule bios over on AotW.

For a deeper dive, I recommend James R Hagood’s Memoirs of the First South Carolina Regiment of Volunteer Infantry … an unpublished manuscript he wrote shortly before his death in 1870. It’s online and downloadable [17MB pdf] from the University of South Carolina. JR Hagood was Sergeant Major and acting Adjutant of the regiment at Sharpsburg in 1862 and was appointed Colonel in November 1863 over half a dozen officers senior to him.

Notes

Knotts’ resignation letter is from his Compiled Service Records; I found it online from fold3 (subscription service). Here’s the useful part of the front of the page:

Brig. Gen. Jenkins’ comments transcribed:

Nov. 14, 1862

Capt. Knotts being totally useless as an officer, it is recommended that his resignation be accepted, & he be allowed to join the Ranks.

M. Jenkins

Brig. Genl.

Thanks to Jim Smith for locating Hagood’s manuscript, an excellent resource with details about the regiment, its officers, and individual casualties.