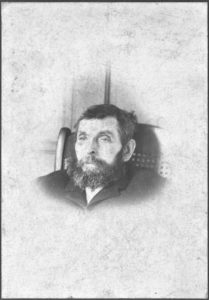

James Burke (c. 1887)

10 January 2024

Private James Burke of Company D, 27th Indiana Infantry was wounded at Antietam on 17 September 1862. Here he is perhaps 25 years later, about the time he began receiving a government pension for his war service.

Thanks to Polly Kaczmarek for this photograph. She got it from her grandmother, who was James’ granddaughter.

Polly notes the similarity with the photocopy, below, of a picture found in his pension file in Washington, DC. In it, as she says, he’s “shirtless and scrawny,” at least in part due to his wartime experiences.

Willard Dean Tripp had early war service as a Corporal in the 4th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, a 3-month unit, then helped form a new company and was commissioned their Captain in December 1861. They became Company F of the 29th Massachusetts Infantry, part of the famous Irish Brigade at Antietam. He led them for 3 years and was briefly the regiment’s Lieutenant Colonel near the end of his term in December 1864.

The fine photograph above is among the holdings of the US Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC) in Carlisle, PA.

The USAHEC has another picture of him, this one taken later in the war; he looks to have aged a bit. It’s from a page in Volume 117 of the MOLLUS Massachusetts Collection.

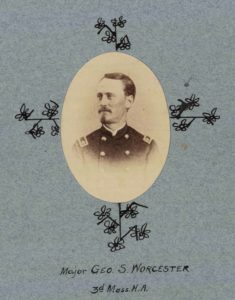

Major George S. Worcester (c. 1864)

4 January 2024

Given the moniker George Samuel Franklin David Worcester at birth, he dropped the Franklin and David as a young man to be afterward known as George Samuel Worcester. He was a Sergeant in the 13th Massachusetts Infantry when he was wounded at Antietam in September 1862. After recovering, he was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery and was successively promoted to Major by the end of the war.

He’s pictured here at that rank in an Alexander Gardner photograph in the MOLLUS Massachusetts Collection at the US Army Heritage and Education Center.

There’s another copy of this image, on a CDV, in the Boston Public Library.