An English saddle in wartime Richmond

28 July 2025

Behold a receipt for an English Saddle & Equipments purchased by Sharpsburg veteran Major, soon to be Lieutenant Colonel Henry A Rogers of the 13th North Carolina Infantry in Richmond, VA in July 1863. It was $125.

For reference, due to wartime shortages and inflation, bacon cost $1.25/pound and flour was $28/barrel in Richmond, four times their pre-war prices. And his pay was $130/month for May and June 1863, while still a Captain. It would rise to $150/month as a Major and $170 as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Rogers’ saddle was probably made in the Ordnance Harness Shops at Clarksville, VA, but may instead have literally been English-made and came through the blockade from England.

The W.S. Downer seen on the receipt is Major William S Downer, Superintendent of Armories at the Richmond Arsenal, the organization responsible, among other things, for issuing horse equipment of all kinds. M S K = Military Storekeeper. Downer, by the way, had been a clerk at the US Army’s arsenal at Harpers Ferry, VA in 1860.

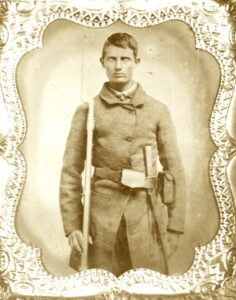

Here’s Henry Rogers at about the time of his purchase, in a portrait of unknown provenance from the Chancellorsville Vistor Center.

Notes

The receipt above is among Rogers’ Compiled Service Records, now in the National Archives. I got my copy from fold3, a subscription service.

The 13th Alabama Infantry in Maryland, in detail

19 July 2025

Private “Mage” Allen, Company H [Alabama Archives]

I’ve just completed a thorough scrub through the military and other records of the men of the 13th Alabama Infantry regiment, and extracted service and personal details for those who were present on the Maryland Campaign of September 1862.

Following is some interesting information that comes from that collection of data.

Savage shoes

1 July 2025

This from the Terrell, Texas Register by way of the of Fairfield Recorder of 28 August 1896. I’ve not found who “old Hannah” was, but Joe Savage was a Sharpsburg veteran, a Private in the 13th Alabama Infantry. He lost his lower leg and foot to amputation two weeks after he was wounded at Jones’ Farm near Petersburg, VA on 30 September 1864.

Notes

I remember seeing stories like this before – but can’t place them now. Please comment if you know of others. The Fairfield Recorder is online through the Portal to Texas History from the University of North Texas Libraries.