Getting on with the War

19 January 2007

Pontoon bridge at Berlin, Md., October 1862

In the last week of October 1862, General George McClellan crossed the bulk of his Army of the Potomac into Virginia, ready to again do battle with General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. It was the first significant movement of the Army–outside of the scrap at Shepherdstown on 19-20 September–since the Battle of Antietam.

Conventional wisdom has it that McClellan had stalled continuously since Antietam in defiance of President Lincoln’s impatience with the lack of pursuit of Lee’s battered ANV, and that the President fired the General immediately after the election in November for that lack of aggressive action.

But is this too simplistic?

There are few writers who improve on the stereotypical views of McClellan’s personality and generalship. My view is that caricature is poor history, and that little about him is likely as simple as most authors present. I’m not interested in defending or rehabilitating the General–personally, I wish he’d done many things differently–but I cringe at the mindless and poorly supported portrait usually painted.

Giving General McClellan more credit, or at least the benefit of a closer look, is not an entirely new phenomenon, however. The two page photo spread above is from Miller’s Photographic History of the Civil War (1912). Perhaps you’ll be struck, as I was, by the unusual flavor of the text beneath the picture:

McCLELLAN’S LAST ADVANCE – – – THE CROSSING AFTER ANTIETAM

This splendid landscape photograph of the pontoon bridge at Berlin, Maryland, was taken in October, 1862. On the 26th McClellan crossed the Potomac here for the last time in command of an army. Around this quiet and picturesque country the Army of the Potomac had bivouacked during October, 1862, leaving two corps posted at Harper’s Ferry to hold the outlet of the Shenandoah Valley. At Berlin (a little village of about four hundred inhabitants), McClellan had his headquarters during the reorganization of the army, which he considered necessary after Antietam.

The many reverses to the Federal arms since the beginning of the war had weakened the popular hold of the Lincoln Administration, and there was constant political pressure for an aggressive move against Lee. McClellan, yielding at last to this demand, began advancing his army into Virginia.

Late on the night of November 7th, through a heavy rainstorm, General Buckingham, riding post-haste from Washington, reached McClellan’s tent at Rectortown, and handed him Stanton’s order relieving him from command. Burnside was appointed his successor, and at the moment was with him in the tent. Without a change of countenance, McClellan handed him the dispatch, with the words: “Well, Burnside, you are to command the army.”

What ever may have been McClellan’s fault, the moment chosen for his removal was most inopportune and ungracious. His last advance upon Lee was excellently planned, and he had begun to execute it with great vigor–the van of the army having reached Warrenton on November 7th, opposed only by half of Lee’s army at Culpeper, while demonstrations across the gaps of the Blue Ridge compelled the retention of Jackson with the other half in the Shenandoah Valley. Never before had the Federal military prospect been brighter than at that moment.

Not much like the way that situation is presented by most modern writers, is it? It’s not purely objective history either, but it does bring some variety to the story.

____________________

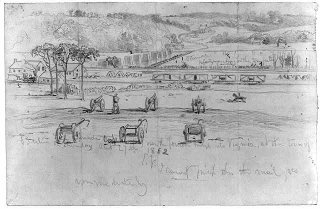

Speaking of pontoon bridges … combat artist Edwin Forbes sketched this from the Maryland side showing “Burnside’s [IX] Corps marching over the pontoon bridge into Virginia, near the village of Berlin [Maryland] on Monday Oct 27th 1862”. “Cannot finish this”, he noted, “the mail leaves immediately.”

In this sketch and in the photo above you can see the naked pilings from the 1858 bridge. It had been fired by Confederate cavalry in June 1861. It was repaired in 1863 and replaced by the present iron railroad bridge in 1893.

____________________

Notes

Top photo, caption text: Miller, Francis Trevelyan (1877-1959), The Photographic History of the Civil War, New York: The Review of Reviews, 1911-12, Vol. 2, pp.56-57. The original photo was probably by Alexander Gardner: others of the Berlin crossing by him are in the Library of Congress online collection.

The main text in Miller’s Volume 2 is by “Henry W. Elson, Professor of History, Ohio University” and the picture descriptions by “James Barnes, author of ‘Naval Actions of 1812’ and ‘David G. Farragut'”. I don’t know which of them wrote the material above, but expect it was Barnes.

Bottom: Forbes, Edwin (1839 – 1895), Burnside’s Corps marching …, 27 October 1862; collection of the US Library of Congress, digital image id: cph 3b26299

January 19th, 2007 at 5:37 pm

You are on a roll. Keep on keepin’ on!

I think you might want to take a look at Edward Hagerman, “The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare”. On page 64:

“McClellan, ironically, was dismissed for inactivity on November 8 while leading over 100,000 men in one of the most impressive strategic movements of the war. His army moved detached from his base of supply at Berlin, a few miles below Harper’s Ferry, to new supply bases at Salem and Rectortown on the Manassas Gap Railroad. The huge expedition left Berlin between October 26 and November 1 and arrived at Salem and Rectortown between November 4 and November 7, the day McClellan received the order from Lincoln remocing him from command.”

Lot’s of good stuff in this book, and plenty to blow the top of your run-of-the-mill Deranged Mac Basher’s head off. While you are doubltess neutral and objective, I’m sure you’re well aware that the Deranged Mac Basher’s credo is “If’n yer ain’t agin’ ‘im, yer agin’ us!”

Harry

January 20th, 2007 at 10:24 am

Thanks for adding that, Harry. I think it furthers the point that there are at least two sides to every story. When people are involved, very little is black-and-white.