David Hunter Strother on Antietam

14 January 2010

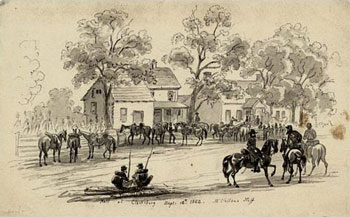

Halt at Clarksburg, Sept 12th 1862, McClellan’s Staff (DH Strother, 1862)

David Hunter Strother (1816 – 1888) – writer, artist and Federal officer – was on General George McClellan’s staff on the Maryland Campaign of 1862. His creative skills resulted is some fascinating artifacts of that period, which I’m enjoying in my study of Antietam and its participants.

Born in Martinsburg, (now West) Virginia, he had trained as an artist in New York and Europe, and was working as a writer and illustrator in books and magazines in his 20’s. His father “Colonel” John – an Army Lieutenant 1813 to 1815 – ran the Strother House hotel in Berkeley Springs.

By the 1850’s D.H. was famous as “Porte Crayon” – his nom de plume. He was on assignment for Harpers Weekly at Harpers Ferry in 1859 and covered John Brown’s trial and execution …

His article on the event concluded with:

… That there are persons at a distance who had sided and encouraged him [Brown] is proven by the captured correspondence. But these white-livered suborners of murder and treason are not dangerous. The head of the fanatical serpent, with its bloody fangs, we have crushed under our heel–Its tail may writhe and rattle, but can not bite.

After the War he described his feeling at the time and how they changed later:

… Now, I was born in Virginia within twenty miles of Harpersferry and the people of the disturbed district were my neighbours, friends & kindred, so it can hardly be presumed that I failed to sympathize warmly with them in their losses & suffering. And as I had never heard of John Brown, until startled by his rash and sudden [unreadable], appearance in 1859, it will not be supposed that my estimate of him differed in the main, from what appeared then to be, the National Opinion at the time.

But when the fire then and there kindled became a devastating conflagration which menaced my country with destruction, I did not hesitate to espouse the Cause of the Nation, and have since marched with its power and opinion, not unwillingly, to the completion realization of John Brown’s [unreadable] ideal.

Thus, while no man may presume to have observed entirely without prejudice, or to have attained infallible conclusions, yet it must be admitted that I have had peculiar opportunities for knowing the things whereof I speak, and have also peculiar motives for dealing fairly with both sides of the question and for rendering justice to all parties immediately concerned in this Great Historic Tragedy.

In June 1861, at age 44, he volunteered as a topographer for the Federal Army at Martinsburg. In March 1862 he was appointed Captain and served as aide-de-camp on the staff of General Nathaniel Banks for his 1862 Valley Campaign.

Being a Virginia Unionist, he was seen as a traitor by his former friends and neighbors. In his journal (1867) he recognized that he was

bitterly hated during the war and am yet no doubt. I replied I took it as a compliment. Next to being beloved being well hated is the most desirable. Had I not been serviceable to my government I should not have been hated– was I not now more respected I should not be hated.

In June 1862 Strother accepted a commission as Lieutenant Colonel of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry regiment, and served as Topographer on General Pope’s staff for the battles of Cedar Mountain and Second Manassas. When Pope went West, Strother obtained appointment to General McClellan’s staff.

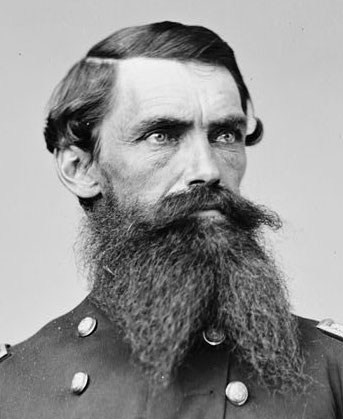

Lt. Col. D.H. Strother (c. 1862, Library of Congress)

His diary describes his arrival:

SEPTEMBER 9, TUESDAY. Warm and cloudy. … I left the city [Washington] at three o’clock. The road to Rockville was filled with trains and stragglers. It was hot and dusty and I arrived at the town about sunset. To the left of the town, half a mile toward Great Falls was the encampment of McClellan’s headquarters on an open hill. The Commander greeted me cordially, recalling the last time we had met at Charles Town. He then formally asked me to become a member of his staff, to which I consented. After this, maps were produced and the General stated his plans to me. He had information which, he said, he could not reject that the enemy lay behind Monocacy a hundred thousand strong.

[…] I gave the General all the information I had about the Ridge, the towns, the fords and crossings of the Monocacy, and the country about Frederick back to Harpers Ferry. We then discoursed generally about army matters. He said his cavalry had entirely the prestige of Stuart’s, having cowed it in many combats so that it would not stand at all. Our conversation was clear, unembarrassed, and agreeable. On parting the General pressed my hand warmly and expressed great satisfaction at the information I had given him, his gratification at having me upon his staff, etc. I replied that it was a position I had coveted from the beginning and hoped I would be useful. This kind, manly reception, so different from the manner of Pope, reveals the secret of McClellan’s popularity with the officers and men. . .

Interesting commentary on Pope, and to hear McClellan’s opinion of the Confederate Cavalry – hardly what we think today about that period in the War. Nearer Frederick he wrote:

SEPTEMBER 11, THURSDAY. […] We are all packed for starting, harnessed, and tents partly struck. It promises to be a rainy day … We moved about four o’clock across the fields to the Frederick road. McClellan’s staff is quite numerous and of high rank. It is about fifty strong with two generals and a half a dozen or more colonels. There is more appearance of military etiquette and soldierly bearing about it than I have yet seen On a little meadow near the Seneca our tents were pitched.

I fell into conversation with an officer next to me. He talked of Berkeley Springs and mentioned many incidents of the past year familiar to me but which I did not think were generally known. He then asked of the geography of the country and the enemy’s probable intentions. He took me to his tent and I discovered it was General Marcy, McClellan’s father-in-law and chief of staff. He here showed me telegrams from divers points to show that the enemy had no troops in front of Washington but was massed with his whole force on the Monocacy. Further that a movement en masse had been commenced toward Hagerstown and the points in front (east) of the Monocacy had been abandoned. The cavalry at New Market that Burnside was ordered to attack had also yielded with little resistance.

The retrograde movement on Hagerstown I said meant a retreat into the Valley of the Shenandoah by way of Williamsport. This seemed to be the received opinion…

Another interesting tidbit here in the thought that the Confederate Army was heading north and west to return to Virginia. If this was McClellan’s view, what did he see as his mission at that point? After the next stop Strother wrote:

SEPTEMBER 12, FRIDAY. Cloudy and warm. Tents struck at eight o’clock and the staff took the road early. Talked further with General Marcy as we rode. The indications seemed to confirm our last night’s judgment of the places of the enemy. General White was at Martinsburg with several thousand men, Colonel Miles at Harpers Ferry with ten thousand. The enemy’s movements might have the additional eclat of enveloping and destroying these corps. To prevent it, we must press him. . . . A mile before reaching Urbana we halted in a lovely grove surrounded by grass fields like shaven lawns. Here camp was pitched. . . .

On arriving:

SEPTEMBER 13, SATURDAY. Fair and pleasant. Started early and entered Frederick City at about ten o’clock. Here an ovation awaited us that touched the inmost soul. The whole city was fluttering with Union flags. From windows and balconies handkerchiefs were waving while faces beamed with joyful excitement filled every opening. The sidewalks were crowded with citizens of every age, sex, and color. No formal cheering, no regulated display, but a wild spontaneous outcry of joy. Old men rushed out and barred the passage of our cavalcade to grasp the hand of McClellan. Ladies brought out bouquets and flags to decorate his horse. Fathers held up their children for a kiss and a recognition…

Lee entered Maryland evidently indulging the hope that the state would use and welcome the Confederate army. The cold reception, the terror of the sentimental Secessionists, the fact that he lost five men by desertion where he got one recruit, must soon have disenchanted him and caused his retrograde movement, preparing for a return to Virginia by Williamsport. After provisioning and refitting the army to the extent the country affords, this will be his course, gobbling up Miles at Harpers Ferry and White at Martinsburg if possible. The enemy’s troops behaved well towards the country and citizens better than ours will do, I fear …

This is just one of the several witness descriptions of the Army’s reception in Frederick that I’ve read. It sounds somewhat over-dramatized – as some writing of this period can – but is similar in feel to others. It is likely it was actually as enthusiastic as described.

On the action at Turner’s Gap on South Mountain:

SEPTEMBER 14, SUNDAY. Pleasant. Some distant guns at intervals. Troops all moving westward over the Catoctin ridge and into the Middletown valley. We rode rapidly to Middletown and there the Commander stopped at Burnside’s quarters in a field at the eastern end of town. I was sent for by the commander-in-chief who wished me to find a man true and reliable to go to Harpers Ferry to carry a message to Miles. I found an acquaintance and endeavored to make the arrangement. A Dr. Baer assisted me.

About two o’clock news came that the enemy disputed the passage of the ridge in force. The staff mounted and rode forward, taking position between two batteries on a high spur from whence most of the localities were visible … [Sturgis’] glittering columns could be seen for a mile, crawling up the winding road … Hooker moving up toward the same crest and a bald summit behind it with a division of fifteen thousand men … musketry on the left was long continued and rapid, but at length got out of hearing over the ridge, showing that Reno had driven the enemy … During this contest we could hear heavy thugs of cannon and musketry from Franklin’s attack at the Burkittsville pass, three or four miles distant.

As night fell, the fight on the turnpike with Gibbon became hotter and more interesting … We watched this contest till nine o’clock, then the staff rode off to a house on the road about a mile toward Middletown …

White, it was thought, had retired from Martinsburg and joined Miles at Harpers Ferry. Miles having withdrawn from Maryland Heights, our troops were concentrated on Bolivar Heights, while Jackson was moving via Williamsport and Martinsburg to intercept their retreat on Romney. This news Captain [Charles H.] Russel of the Maryland cavalry brought. The question tonight was whether the enemy would retire during the night or reinforce and dispute the pass.

Enroute to Sharpsburg:

SEPTEMBER 15, MONDAY. Fair. . . . The morning news has assured us of further success. Franklin has forced the pass at Burkittsville and gangs of Rebel prisoners are occasionally seen passing toward Frederick … at Boonsboro we stopped at a white house on the entrance to the town. … I reported to McClellan and then told him what I had heard from Booth, that the cavalry had (under Fitzhugh Lee) taken the pike to Hagerstown. “I know it,” he said. “Pleasonton has followed and taken 250 prisoners.” The masses of enemy infantry have moved to Sharpsburg. “There we are going to press them,” he said quietly. Thus the alert and far-seeing Chieftain has already known and provided for everything. So we mounted and rode rapidly to Keedysville, halfway to Sharpsburg. The whole road was through masses of troops and our movement was escorted by one continuous cheering. Stopping on a hill half a mile beyond Keedysville, we drew up to reconnoiter the enemy who opened on us a rapid fire from two batteries. It did no damage that I could hear of …

SEPTEMBER 16, TUESDAY. Cloudy and warm. I was told that Miles had surrendered his whole force ignominiously at Harpers Ferry, ten thousand men. Did I not know that some damning misfortune was in store for us? The personnel of the staff remained nearly all day lying about the church with General Williams. I became restless and rode to the front … When I got to Newcomer’s [Pry’s?] brick house where headquarters were, I found the General about to ride out. I joined him and we rode several miles to the right, crossing Antietam and flanking Sharpsburg in that direction … The staff at length reached the position where Hooker was posted. Large bodies of troops were moving to the right and pushing forward through the woods cautiously, shelling in front of them wherever the enemy appeared in any number. Hooker recognized me and called to me and shook hands in a very friendly manner. Having put these troops in, we returned to Newcomer’s. … I believe the enemy are not before us in force.

Majr. Genl. George B. McClellan: at the Battle of Antietam (1862, Currier & Ives)

Colonel Strother admires the “the alert and far-seeing Chieftain” who “has already known and provided for everything”. The kind of admiration, it seems, that begs for an image of the General like that in this Currier & Ives print.

He describes the day of the main action:

SEPTEMBER 17, WEDNESDAY. Clouds and threatening rain. While at breakfast the cannon opened. The battle was evidently commencing. This was about 7:30 A.M. The fruits of Hooker’s movement presently became apparent by the flight of Rebel troops from the wood on the right and the opening of musketry. Sumner’s Corps was ordered up to fill a gap between Hooker and the center, and his columns could be seen moving beautifully into position. On the center Generals Richardson and Meagher moved in handsomely and joined battle. … Franklin advanced to reinforce Sumner, while on the left Burnside with thirty-five thousand men made a flank movement to strike Sharpsburg by forcing a bridge over the Antietam one mile from the town.

Up to ten or eleven o’clock artillery fire raged along the whole line while musketry was heavy on the center and right. The right advanced, the center was checked but held its ground, Burnside made no progress at the bridge, which was fiercely defended. I went forward with a message to General Pleasonton of the cavalry to advance two squadrons on the turnpike to reconnoiter Sharpsburg. Pleasonton answered gallantly, “I will do it, Sir,” and ordered up the squadrons.

Hooker was driving the enemy when I returned to the General … McClellan was in high spirits. “It is the most beautiful field I ever saw,” he exclaimed, “and the grandest battle! If we whip them today it will wipe out Bull Run forever.” I answered, “Fortuna favet fortibus”.

Fitz-John Porter’s Corps fought under Burnside, while Porter him self remained with McClellan as counselor. They sat together during the morning in a redan of fence rails, Porter continually using the glass and reporting observations, McClellan smoking and sending orders.

His manner was quiet, cool, and soldierly, his voice low-toned. I perceive he liked all about him to speak in low tones. The intense excitement under his manner was also very apparent. Presently news came that Hooker was wounded, that Mansfield was killed, and that Burnside’s progress was unsatisfactory. He took the bridge and said he could hold it. A message was sent to him that if he could do no more, his command would be transferred to some other work.

Pleasonton had advanced two batteries on the center which were doing good work. Sumner was checked and a Rebel division poured from the disputed wood and advanced at full charge on his position across an open field. Their rush was at double-quick and was fearful to see. As they advanced they were hid from our view by a wood and the smoke of some burning buildings which the enemy had fired in the morning. The fire of Sumner was tremendous, and after some time of suspense the debris of the Rebel column was seen fleeing disorganized back across the open ground, followed by a storm of shells and balls.

[…] The Irish brigade made a gallant rush on the center and forced the enemy back behind his batteries. Captain Graham’s battery then advanced most gallantly under a tremendous fire of at least forty guns and took position at short range, whence he opened on the enemy with effect … By one o’clock there was a general lull all along the line. Then came in news of more generals fallen Sedgwick wounded, Richardson wounded, Hartsuff wounded, Dana wounded. A feeble note from Sumner complaining that his command was cut to pieces and desiring reinforcements. All wore a serious air. From the signs of the day and the report of the prisoners it was evident the enemy was before us in full power, and the fact that he had risked a battle in his present position showed that he felt great confidence in his power.

From one to four the fight lulled almost entirely. General McClellan rode over with two or three aides to see Sumner … At four o’clock the battle reopened by our attack all along the lines. Our exhausted ammunition had been replenished and the troops breathed. We carried the wood on the right and Burnside made his grand effort. His advancing rush was in full view and magnificently done. He carried the height and took a battery, but the enemy had massed his infantry behind the crest and their ordnance overthrew the blow and decimated the regiments which had gained the summit. The crest was regained and held by the enemy, and our troops driven down the hill stood doggedly and held the halfway ground when night closed …

We rode back to our headquarters camp at Keedysville, where a good supper and a good night’s rest closed the day of the great battle. The armies in round numbers were a hundred thousand men on each side. The Rebels chose their position and we attacked. McClellan and Lee met face to face in a grand pitched battle on a fair field. Neither side can make excuses or complain of disadvantages. As far as the day went, we beat them with great slaughter and heavy loss to our selves. How decisive the results of the action, time can only show when the smoke and dust shall have been blown away. Toward evening the enemy sent troops to secure and hold the fords on the Potomac behind them. This looks like retreat.

And the next day:

SEPTEMBER 18, THURSDAY. Clouds which lifted about nine o’clock. We have thirty-two thousand fresh men to put into battle today if it recommences. The enemy will not attack from all appearances. The orders given to our generals were to hold their positions but not to attack. To Burnside it was to withdraw the troops over the Antietam if he could do it safely …

D.H. Strother remained with General McClellan until the General was relieved in November, at which time he returned to Banks’ staff and saw action in Louisiana at Port Hudson and on the Teche Campaign. He was in Washington, unattached, during the Gettysburg Campaign, and in July 1863 was promoted to Colonel of his regiment (though he never actually commanded it in the field). He was after on the staffs of General Benjamin Kelly, Franz Sigel – in action at New Market, VA – then (cousin?) David Hunter in the Valley of Virginia. He resigned from the army on 10 Sept 1864 when Hunter was replaced by Sheridan.

After War’s-end he was honored for service by brevet to Brigadier General of Volunteers, in August 1865. He was Adjutant General of Virginia militia into 1866, thereafter returned to West Virginia and ran the family hotel, wrote and drew. He was US Consul to Mexico City 1879 – 1885 under Presidents Garfield and Arthur.

Notes

_____________

The photograph of Strother in Lieutenant Colonel’s uniform above is from an original glass plate negative at the Library of Congress. I’ve flipped it to be right-reading.

Strother’s diary was published in A Virginia Yankee in the Civil War (Cecil D. Eby, Jr. ed., Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1961), which has been posted online in the Internet Archive. I’ve freely chopped and excerpted from Chapter V, pages 102-112. I encourage you to see the full version for yourself.

A gallery of his art is hosted online by West Virginia University: also source of the images at the top and end of this post. The picture at the bottom is an undated self portrait.

The quote about Brown – and Strother’s opinions of him – are from a lecture Strother gave on the subject in 1867 in Cleveland, Ohio. See a lovely exhibit on the lecture and more background on the circumstances from WVU. The site also provided the 1867 journal quote.

The Forbes sketch of General McClellan entering Frederick is from the Library of Congress’ collection. As is the dramatic 1862 Currier & Ives representation of the General at Antietam.

Military service dates for both Strothers from Heitman.

September 24th, 2010 at 5:54 am

You write: In June 1862 Strother accepted a commission as Lieutenant Colonel of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry regiment.

West Virginia wasn’t a state until 1863. Prof. Eby writes on p.121 of his biography of David Hunter Strother that Strother was commissioned Lt.Colonel of the Third Mounted Regiment of Virginia Volunteers.

Eby also writes, on p.5 of Strother’s biography, that John Strother was a lieutenant colonel in the 67th Regiment of Virginia militia by the 1820’s.

If I read Heitman correctly, the John Strother he lists died in 1815. My g-g-grandfather died in 1862.

March 30th, 2011 at 10:18 pm

I enjoyed the article & photo. I have a Strother in the family tree, not much info about her other than her marriage notice. I came across this site while seeking general “Strother” info. David Hunter Strother seems to have been a talented & controversial man. His photo shows a handsome man,too. Although the beard is “impressive”, I think I’d prefer him clean shaven!

April 5th, 2014 at 10:27 am

Strother’s complete work, “Personal Recollections of the War,” as published in HARPER’S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE, is on-line at the Making of America website.