The Antietam observation tower and the birth of the Park

1 December 2018

My project on the visual history of the Antietam National Battlefield continues, focused today on one of the most iconic features on the field – the Observation Tower. Since it was built in 1896 the tower has been a central memorial and educational feature of the National Battlefield, and it has always been a popular destinations for visitors.

So how did it come to be, and how has its story evolved in the last 122 years?

It starts with the origins of the battlefield park itself.

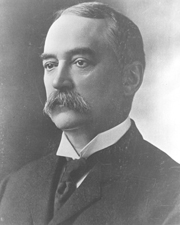

In June 1890 US Congressman Louis Emory McComas (Md-6) introduced legislation to establish a formal National Battlefield Park at Antietam (H.R. 10830). Unfortunately, for lack of support, it went nowhere. But McComas is one of the heroes of Park history because he didn’t quit there.

L.E. McComas c. 1898 (US Senate Historical Office)

In August, he pushed a 2-sentence paragraph of text into an annual sundry civil spending bill:

For the purpose of surveying, locating, and preserving the lines of battle of the Army of the Potomac and of the Army of Northern Virginia at Antietam, and for marking the same, and for locating and marking the position of each of the forty-three different commands of the Regular Army engaged in the battle of Antietam, and for the purchase of sites for tablets for the marking of such positions, fifteen thousand dollars. And all lands acquired by the United States for this purpose, whether by purchase, gift, or otherwise, shall be under the care and supervision of the Secretary of War.

The bill passed both houses with that language and was signed by President Benjamin Harrison on 30 August 1890. Although very narrow in scope, it was enough. It is the initial legal basis for the Park we love today. It wasn’t until August 1895 that Congress passed a bill formally establishing Antietam as a National Military Park.

To oversee the work required in the new law, Secretary of War Redfield Proctor established the Antietam Battlefield Board, and appointed Colonel John C. Stearns and General Henry Heth as members in June 1891. These two old veterans, neither of whom was at the battle of Antietam, made slow progress due to illness and lack of resources. By early 1894 they had consulted with surviving veterans, marked the lines of battle with some 200 wooden signs nailed to trees, and had mapped positions of the military units at the Division level. They had not yet acquired any land for the planned tablets, monuments and access roads. In August of that year Colonel Stearns resigned for reasons of health.

By then, a rather more active man had been appointed Secretary of War.

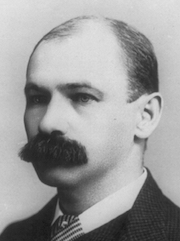

Daniel Scott Lamont was a long-time political associate and friend of Grover Cleveland, and was appointed to the post at the beginning of President Cleveland’s second (non-consecutive) term in March 1893. He was not happy with the progress at Antietam and, in October 1894, appointed a new, expanded Battlefield Board to expedite the work.

As its President he chose Major George Breckenridge Davis of the Judge Advocate General’s Department.

Although not at the battle of Antietam, Major Davis had enlisted service in the Civil War, attended West Point afterward, and had more than 20 years experience as a cavalry officer in the West and as an instructor at West Point. He became an expert in Military law and was known as a savvy administrator.

He was on the Antietam Board for less than a year before being promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and sent back to teach at West Point in August 1895, replaced, confusingly, by Major George Whitefield Davis, USA. In that short time, though, he had a huge impact on the future of the battlefield. His plan for the Park and approach to preservation set the pace at Antietam for most of the 20th Century.

His was a low-cost, low-impact strategy: to purchase narrow strips of land to mark the positions of the troops and to carry access roads from which visitors could view the field, but not buy up the bulk of the land over which the battle was fought, as was the happening at the time at other battlefields like Gettysburg and Chickamauga.

An observation tower was part of that strategy, to allow visitors to see all of the battlefield even though they couldn’t walk the ground, which remained in private hands. Major Davis originally planned two towers – one at each end of the battlefield. He first thought they should be of wood construction but then decided on stone, each to be 16 feet square and about 16 feet tall, with wooden viewing platforms and stairs.

Tower location on the Board’s Preliminary Map of the Antietam Battlefield (1894, Library of Congress)

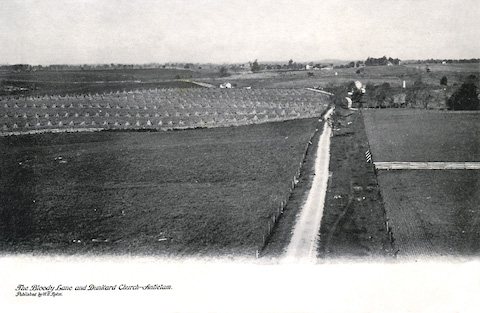

The first such “stone observatory” was built on the high ground at the east end of the Bloody Lane between July and September 1895, when it was opened to visitors. A second tower elsewhere on the field apparently fell out of the plan and was never built.

The following year a significantly larger effort was mounted. In July 1896 the Board awarded a contract to Jacob Snyder of Sharpsburg (his brother James also worked for the Board building battlefield roads) to construct a stone tower 16 feet square and 54 feet high to a new design by the Army Quartermaster General’s Office. It was to have iron stairs and rails and a hip roof, and be constructed of local, native materials.

In August Snyder removed the existing tower and dug a new foundation on the same spot, then began quarrying blue limestone at Hagerstown. In October he found that the Hagerstown quarry could not supply the quantity he needed, so he arranged for bluestone from Indiana to complete the job. He and his crew completed the tower masonry and installed the iron stairs in November 1896.

The tower was accepted by the Government and opened for use by the public in December 1896. Total cost was about $3,800 (about $114,000 in 2018 dollars), but the tower was completed without a roof due to lack of funds.

To cover the stone coping at the top of the tower the Board contracted with the McShane Foundry in Baltimore in late 1896 or early 1897 to cast 8 bronze plates embossed with arrows showing direction and distance to battlefield and other local landmarks. The Government supplied a 1900 pound bronze cannon barrel for the raw material – from a gun that had been at the battle of Antietam. The foundry melted down and re-cast that bronze for the coping plates, and also to create 6 memorial plates to be attached to the mortuary cannon on the battlefield, and for an identification plaque to be used on the tower itself.

Here’s one of those 6 memorial plates – on General J.K.F. Mansfield’s mortuary cannon in the East Woods at Antietam:

A red clay tile roof and supporting framing were added to the tower by the Quartermaster General of the Army between August 1908 and April 1909 following an inspection in early 1908 which had noted the missing roof and resulting weather and drainage issues inside the tower. The bronze coping plates were cut away in the four corners to allow for placement of the roof piers.

I’ve long enjoyed the visual pun embodied in a picture of a Lincoln automobile at Antietam (there’s another of this car at the Burnside Bridge, see another post). But this photograph offers other interesting features too.

The most obvious is an early look at that 1908/09 roof. Another item, which you won’t find on the tower today, is the 1897 bronze plate which is mounted below the lower window on this south facing side of the tower. Zooming in as far as I could on the image …

… I think it says:

Erected 1896. Daniel S. Lamont, Secretary of War Geo. W. Davis, Antietam Ezra A. Carman, Battlefield Henry Heth. Board

Sadly, that plate was stolen in 1969, so I’ll not be getting a better photograph of it.

In the years before the Visitor Center was built in 1962, the tower was a focal point for Park visitors due to its location at the Bloody Lane as well as its commanding height and wide view of the battlefield.

Unfortunately, due to the distance to the nearest public “comfort station”, at the National Cemetery, the tower also sometimes served as a public bathroom. And ever since the 1930s park superintendents have complained that the tower was a magnet for local rowdies, especially at night, and a target of graffiti and other minor vandalism.

The tower was also part of the story of the Park’s second Superintendent, George H. Graham, who had that position from August 1912 to January 1914. Graham was a man with a serious drinking problem and a fondness for firearms, which was a toxic combination. He was eventually fired for gross misconduct, after, among other things, pointing a shotgun at a visitor in the tower in 1913.

Although the tower has looked about the same since 1908, the ground around it appears a little different today. The most visible changes occurred when the Park Service re-routed the tour road to parallel the Sunken Road (rather than running in it) and added a parking lot at the tower in 1965/66, and when the Irish Brigade monument and plaza were installed near the tower entrance in 1997.

Personally, I’m conflicted when I look at the observation tower. The purist in me would rather the battlefield looked exactly as it did at the battle, without that great huge tower. It was not, of course, part of the landscape the soldiers saw in 1862. But it has become an integral part of the Park and the visitor experience, as well as something of a national landmark in its own right.

I don’t think it’s going anywhere anytime soon. And that’s a very good thing.

____________________

Notes and Sources

Louis Emory McComas career highlights – from his Congressional Biography:

1846 – Born near Hagerstown 28 October;

1866 – Graduated from Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA;

1868 – Admitted to the bar and practiced in Hagerstown;

1876 – Unsuccessful Republican candidate for Congress;

1882 – Elected as a Republican to the Forty-eighth and to the three succeeding Congresses (4 March 1883 – 3 March 1891);

1892 – Secretary of the Republican National Committee;

1892 – Appointed by President Benjamin Harrison in November as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (to 1898) and was a professor of international law, Georgetown University;

1898 – Elected as a Republican to the US Senate and served from 4 March 1899 – 3 March 1905;

1905 – Appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as a justice of the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia;

1907 – Died in Washington, DC on 10 November, buried in Rose Hill Cemetery, Hagerstown.

Bonus tidbits on the McComas/Byron Congressional dynasty: McComas’ granddaughter Katherine Edgar Byron (1903 – 1976) was the first woman elected to the Congress from Maryland, in a special election after her husband’s death in a plane crash in 1941. With campaign help from his mother, her son Goodloe Edgar Byron (1929-1978) won a seat covering much of the same part of Maryland in 1970. He’s buried in Antietam National Cemetery. Goodloe’s widow Beverly B.B. Byron (1932 – ) was elected to serve Maryland’s 6th District in Congress in 1978 and served 7 terms. She sponsored the cruiser USS Antietam (CG-56) at its launching in 1986.

The “sundry civil” bill of 1890 which first authorized the Park was formally titled An act making appropriations for sundry civil expenses of the Government for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, eighteen hundred and ninety-one, and for other purposes, and is an appropriation (funding) measure, rather than an authorization. This kind of action would be called an “earmark” today. The full text of the bill is available from the Library of Congress as a PDF. See page 401 for the Antietam paragraph.

By way of comparison to the $15,000 appropriated for Antietam in 1890, an act of 20 August 1890 creating the first battlefield park, Chickamauga & Chattanooga National Military Park, appropriated $125,000 in that first year.

Secretary Lamont’s picture is from a photograph at the Library of Congress.

See more about George B. Davis in an excellent piece by Colonel Fredric R. Borsch in Army History magazine (Winter 2010), online in PDF from the Library of Congress. That’s also my source for Davis’s 1900 picture. Davis retired from the Army as a Major General in 1911 with 48 years’ service. He had been the Army’s Judge Advocate General since 1901.

The Map above is part of Northwest, or no. 1 sheet of preliminary map of Antietam (Sharpsburg) battlefield, online and zoomable from the Library of Congress. It was drafted in 1894 for the Battlefield Board by Jedediah Hotchkiss based on an 1867 map by US Army topographical engineer Nathaniel Michler. It turned out to have some inaccuracies and was superseded by the 1904/1908 series known as the Carmen-Cope maps, but it is sufficient for this purpose, and contemporary with the tower construction.

By the way – War Department contractors James and Jacob Snyder and their family were Sharpsburg residents at the time of the battle. Older brother James, then 16, returned to the family home in town after the battle to find ‘little heaps of dusty rags’, which were ‘discarded filthy Confederate uniforms shucked by the soldiers who had exchanged them for the Snyder boys’ clothes’ – from Kathleen Ernst’s Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign (1999), pg. 160.

My main source on the construction of the Observation Tower is the beautifully documented report [PDF] of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) from the Summer of 2009, Susan C. Hall, historian. It’s online thanks to the Library of Congress.

Other details here are from the bible of early Antietam Battlefield Park history: Charles Snell and Sharon Brown’s Antietam National Battlefield and National Cemetery, Sharpsburg, Maryland: An Administrative History (1986). It’s online from the National Park Service.

Thanks to Stephen Recker for the kind permission to use his c.1900 W.H. Tipton postcard of the view from the new tower, and for finding O.T. Reilley references in the Antietam Valley Record newspaper for construction dates of the first tower in the Bloody Lane. It’s all in his blog post on Virtual Antietam.

The 1925 photograph of the Lincoln was made by the Ford Motor Company (Henry Ford), who bought the struggling Lincoln Motor Company (Henry Leland) for $8M in 1922. That picture is now at the Library of Congress.

All of the modern, color photographs were made by the author.

Please Leave a Reply