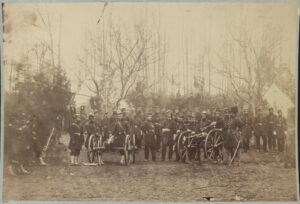

Officers of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry (1861)

4 August 2024

This lovely image was probably taken at the home of the 96th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Camp Northumberland, near Alexandria, VA between December 1861 and March 1862. These, then, are the officers of the regiment at that time and place.

Particularly interesting are the two wheeled weapons at the front of the group.

On the right is a Union Repeating Gun (also known as an Ager Gun or the coffee mill gun). A few of these hand-cranked repeating guns were produced in 1861; apparently President Lincoln was intrigued by their potential and had 10 built. As many as 50 others where produced later. They saw very limited use during the war, and I’ve seen no mention of this one’s actual use by the 96th.

Gathered around that gun are the field and some of the staff officers of the regiment.

In the foreground to our right, left hand on hip, wearing a plumed Hardee hat, is Colonel Henry Lutz Cake, organizer and commander of the regiment. He was an excellent combat leader, which was particularly apparent in action at Crampton’s Gap on 14 September 1862.

Next to him is Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Gellert Frick, a Mexican War veteran. By Antietam in September 1862 he was Colonel of his own regiment, the 129th Pennsylvania. He was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his work at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

To Frick’s right is the Chaplain, the Reverend Samuel Fisher Colt (1817-1893), pastor of the Presbyterian Church in Pottsville. He was discharged in July 1862 and was not on the Maryland Campaign.

Next along to our left is Major Lewis J Martin, a coal mining engineer from Pottsville. He was mortally wounded by a gunshot to his head at Crampton’s Gap and died soon after.

I have not positively identified the next 4 men, but the man with his hand on the wheel may be Dr. Daniel Webster Bland, who was the regiment’s Surgeon from organization to muster out, in October 1864, and later Sixth Army Corps Medical Inspector. I have not confirmed his presence in Maryland in 1862.

The tall man second from left with the luxuriant mustache is probably Assistant Surgeon Washington George Nugent. He had prior service in the 3-month 14th Pennsylvania. He resigned from the 96th on 12 September 1862 to accept appointment as the Surgeon of the 9-month 126th Pennsylvania Infantry, afterward as Surgeon of the 20th Regiment, Emergency Militia of 1863, and then was a contract surgeon at the Fort Delaware post & prison hospital to the end of the war.

The artillery piece in that picture is part of a fascinating story dating to the early organization of the 96th Pennsylvania in September 1861.

A group of Pottsville First Defender veterans, members of the Good Intent Fire Company, formed the Good Intent Light Artillery under Captain Lessig.

The battery … was to be short lived, that is as far as the name was concerned. The members were unable to secure any ordnance to drill with and finally the “boys” decided to swipe brass and make a cannon themselves. Piece by piece they scraped together the brass while some poor, unsuspecting victim scratched his head and wondered at the mysterious disappearance of some article of brass from his shop or household. When enough had been secured the brass was melted and molded into a fine cannon by Geo. W. Snyder …

The Good Intent Battery would undoubtedly have become famous, as the members did, but for an unlooked for occurrence. The 96th regiment had been recruited and lacked but one company. The Good Intent Battery was mustered into this regiment and the members then became infantrymen and “shouldered the cannon” as they remarked for ever afterward. The precious cannon was taken along with the 96th Regt., but was finally turned over to a New England Battery [June 1862], and that was the last seen or heard of it.

Those would-be artillerists became Company C of the 96th, and their officers are seen here around “their” cannon. From left to right, in the foreground, they are:

First Lieutenant Isaac E Severn. He’d served as a Private and Corporal in the Washington Artillery, which became Company H of the 25th Pennsylvania Infantry, from April to July 1861. I can’t specifically place Severn on the Maryland Campaign of 1862, though he may well have been present. He was promoted to Captain of his Company in November 1862 and mustered out with them in October 1864.

Captain William Henry Lessig, later Major, Lieutenant Colonel, and finally Colonel of the 96th Pennsylvania Infantry.

And, I think, 2nd Lieutenant Samuel Rex Russel, with his hand on the breech. He was promoted to Captain of Company H in May 1863, and served out his term to October 1864.

Notes

The photograph of the officers of the 96th is in the collection of the Library of Congress.

The quote above about the Good Intent Light Artillery is from a veteran of the unit in the Pottsville Daily Republican of 18 April 1900, found in a fantastic blog post by Stu Richards.

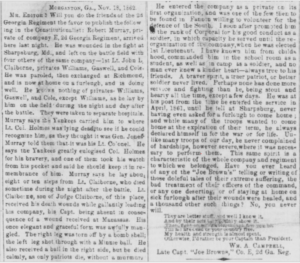

Big thanks to intrepid researcher Laura Elliott for finding and sharing the following clipping from the Augusta, GA Weekly Constitutionalist of 3 December 1862. She also posted it (and a transcription) to the Civil War Talk discussion group.

The primary subject of the letter quoted here was First Lieutenant John L. Claiborne, who was in command of Company E, 2nd Georgia Infantry when he was mortally wounded at Sharpsburg on 17 September 1862. He died sometime during the night after the battle.

Here’s what I’ve found about the other named individuals:

The letter’s author, William A Campbell, was born about 1830 in North Carolina and in 1860 was a married 30 year old attorney of modest means with 3 children living in Morganton, GA. He enrolled on 26 April 1861 as the original Captain of the “Joe Browns” – Company E of the 2nd Georgia Infantry. He was ill in the first months of 1862 and retired or was dropped on 28 April 1862 during the Army reorganization, perhaps then on sick furlough, and probably because he was not reelected Captain. He requested duty in Georgia as an enrolling officer in May 1862, but does not appear to have been appointed. He died in Morganton in 1864.

Battle witness Robert F Murray (wounded and captured at Sharpsburg) was wounded again and disabled for further field service in the Wilderness in 1864 but survived to be paroled in North Carolina in May 1865. I found no further information about him.

Corporal P.K. (or D.K.) Williams died of his wounds in a US Army hospital in Frederick, MD on 21 April 1863. He was then 28 years old. The only available military records for him are from US Army medical files created after Antietam.

Private George W. Gosnell [Gaswell] died of wounds at the Locust Spring field hospital on the Geeting farm near Keedysville, MD on 6 October 1862.

Private William M. Cole survived the war to be surrendered at Appomattox Court House, VA on 9 April 1865. I found no further information about him.

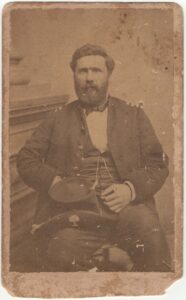

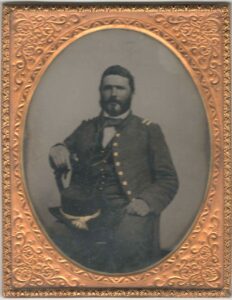

Major James H Dingle, Hampton Legion Infantry (1862)

30 June 2024

Going by Hervey, and sometimes seen as Junior, probably after his grandfather, James Hervey Dingle of the Clarendon District of South Carolina was the 38 year old Major of the Hampton Legion when he was killed at Sharpsburg on 17 September 1862. The Legion was part of General John Bell Hood’s Division and was engaged in ferocious combat in and near Miller’s Cornfield that morning [map].

The shoulder bars on his coat are a bit unusual, but probably represent the rank of First Lieutenant, which he held from 25 April to 20 June 1862, before his appointment to Major.

These photographs were graciously shared by descendant Jeff Dingle, who owns the originals.