Killed by guerillas

30 October 2021

I found a couple of excellent accounts which nicely bracket the military career of Captain Samuel A. McKee, 2nd United States Infantry. They are too good not to share and I hope both of my readers will appreciate them.

McKee was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant, USA on 5 August 1861 and First Lieutenant 5 days later.

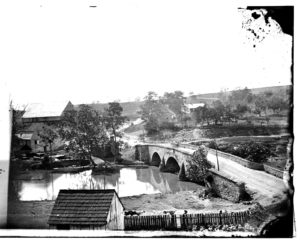

He led Company I of the 2nd US at Antietam, part of a consolidated battalion of companies from the 2nd and 10th United States Infantry regiments. They crossed the creek over the middle bridge about midday on 17 September 1862 and pushed a line of skirmishers up the pike toward Sharpsburg.

Battalion commander Lieutenant John Poland reported “Lieutenant McKee, commanding Companies I and A, Second Infantry, while deploying to the front, was severely wounded and compelled to leave the field.”

Major Norton to President Davis, February 1865

9 January 2021

Captain George F. Norton had been in Confederate service since April 1861 and led the First Virginia Infantry on the Maryland Campaign, seeing combat on South Mountain and at Sharpsburg. He was in command again at Gettysburg, where he was wounded, and afterward was promoted to Major. He was with the regiment to the end of the War – which for him occurred when he was captured at Sailor’s Creek, VA on 6 April 1865.

He jumps headlong out of the distant past, though, in this brief letter he wrote to President Jefferson Davis on 28 February 1865:

Sir,

I respectfully ask to be appointed Colonel of a Negro Regiment –

I am a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute and accompany this application with recommendations from my Brigade and Division Commanders.

I am – Sir – very respectfully,

George F Norton

Major 1st Va. Infantry

I’ve never seen anything like this before.

In February 1865 there were no “Negro Regiments” in Confederate service, nor were any expected. So this seems like an off-the-wall request.

The idea of arming slaves had been argued before, and roundly rejected. In December 1863 General Patrick Cleburne formally floated the idea in a proposal he shared among his officers. Word got around the army, and the reaction was universally and understandably negative. Cleburne either misunderstood or underestimated the power that slavery held in and over the Confederate States.

Most of the leadership probably agreed with Howell Cobb, Georgia politician and Confederate founding-father, who later famously wrote:

I think that the proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began … If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong, but they won’t make soldiers.

When he received the proposal in January 1864, President Davis firmly rejected it and demanded the document and all copies be destroyed.

However, a year later the situation was desperate, and on 10 February 1865, and with the support of General R.E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, Congressman Ethelbert Barksdale of Mississippi introduced a bill (HR-367) authorizing arming slaves in the defense of the Confederacy. It passed the House on 20 February, and slightly amended, by one vote, the Senate on 8 March. President Davis signed it into law on the 13th.

So it may not be such a mystery that Norton wrote that letter. From a prominent Richmond family, with friends in the city, it is likely that he knew of the legislative activity. Perhaps he saw an opportunity for advancement and wanted his name in the running.

I have not found a reply from the President to Major Norton in the record.

_____________________

The CS War Department issued General Orders No. 14 to implement the new law on 23 March. Notably they included these among the provisions:

No slave will be accepted as a recruit unless with his own consent and with the approbation of his master by a written instrument conferring as far as he may, the rights of a freedman …

It is not the intention of the President to grant any authority for raising regiments or brigades. The only organizations to be perfected at the depots or camps of instruction are those of companies and (in exceptional cases where the slaves are of one estate) of battalions consisting of four companies …

The war was effectively over less than a month later, and by that time only two such “companies” had actually been formed.

_____________________

Notes

The image above, of Major Norton’s letter (along with the accompanying recommendations from Generals Corse, Terry, and Pickett, and Thomas Haymond’s forwarding letter) is in the US National Archives in his Compiled Service Record; I found it online from fold3 (subscription required).

The Howell Cobb quote is from a letter he wrote to then-Secretary of War James Seddon on 8 January 1865, which is online from the Encyclopedia Virginia.

The text of the approved Act of the Confederate Congress and of War Department General Orders No. 14 authorizing enlistment of black soldiers is online thanks to the Freedmen and Southern Society Project at the University of Maryland.

George F Norton’s bio page is on Antietam on the Web.

For a deeper look at the issue of enlisting slaves for Confederate service, from an early 20th century perspective, you might consult N. W. Stephenson’s The Question of Arming the Slaves (American Historical Review, January 1913), and Thomas Robson Hay’s The South and the Arming of the Slaves (American Historical Review, June 1919), both online from JSTOR.

[Nathaniel Wright Stephenson (1867-1935), a prolific writer of history and biography was appointed professor at the College of Charleston (SC) in 1902 and at the new Scripps College (CA) in 1927. T.R. Hay (1888-1974) was a Penn State-trained electrical engineer who became a noted historian and editor.]

Piecing a soldier’s story together

18 October 2020

With a nudge from a record in the Frederick Patient List database, I went looking for 2nd Lieutenant J. Corfro of Company I, 1st North Carolina Infantry, only to find he probably never existed, despite his shiny new government-issue marker at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, MD.

The Lieutenant lived only on paper, in Federal hospital and burial records, which have him admitted to a US Army hospital in Frederick in September 1862 and buried at Mt. Olivet after he died on the 20th. He appears in no roster, muster roll, or other military record for the First North Carolina or any other military unit.

I believe he was actually Lieutenant William D. Scarborough, who, incidentally, has an equally nice stone at Mt. Olivet.

The bits of available information about Scarborough, recorded under many names including Corfro, are sometimes confusing and contradictory, but I think I have made some sense of them. Follow along and see what you make of him …