Modern headstones

19 July 2020

I recently tweeted about adding a new bio page for a Georgia soldier, Andrew W Poarch and, somewhat as an aside, noted that his modern headstone has some problems.

He was buried at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, MD in October 1862 and at some point given a basic headstone, now heavily worn.

Much more recently, sometime after 1992, well-meaning persons got him and each of the other Confederate soldiers buried in Mt. Olivet a new headstone from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Probably because of transcription errors in his original burial records, they got his name terribly wrong. Apparently the applicant for the new headstone didn’t dig any deeper – into the soldier’s service records, muster rolls, or family genealogies, for example – to verify his information. Although, to be fair, it’s easier to do that today than it was 20 or 30 years ago.

But now the errors are literally carved in stone.

I’ve seen dozens of markers like these with errors large and small over the years of researching my soldiers, but had not thought to make a list or keep a log of them.

The day after Private Poarch’s, though, I found another such case – the stone for Louisianan Volney L. Farnham at Elmwood in Shepherdstown, WV. It has his first initial/name and his regiment wrong.

And this afternoon a third popped-up: Private William T. Curry of South Carolina. This is his modern VA marker in Dials Cemetery, Gray Court, SC. Minor things, to be sure, but his middle initial and his year of birth are probably wrong.

So taking these 3 stones as huge cosmic hints, I’m starting a visual list here, and I’ll add to it as I find more. I can’t fix them, but I can provide a virtual erratum.

Let me know if you find any more cases like these, won’t you? Or if you have any information that corrects errors I’ve made.

_____________

Gravestone pictures via Findagrave.

_____________

[52] additions after the break …

Dr. Rushton, late of the ‘Bloody 7th’ SC

9 July 2020

I have had a great time pulling a research “thread” this evening and thought both of my readers might like to share in the journey.

Looking into Sergeant John Martin Rushton (1837-1889) of the 7th South Carolina Infantry.

I started with Glen Swain’s excellent roster in The Bloody 7th (Broadfoot, 2014), based mostly on the Consolidated Service Records (CSRs) from the National Archives.

Those records say Rushton was wounded at Sharpsburg in 1862. In November – December 1864 he was in a hospital in Richmond, VA with a gunshot wound in the shoulder, then served as an attendant in another hospital there. He retired in March 1865, presumably for disability, and was paroled at Augusta, GA in May.

Nothing unusual here; it seemed like a typical soldier story until I looked at his gravesite on Findagrave, which refers to him as Dr. Rushton. Not so many enlisted men were later physicians, so I thought I’d find out when and where he trained.

A little digging online with various forms of his name, and up popped an announcement in the Richmond Dispatch that J.M. Rushton of Edgehill [sic], SC graduated from the Medical College in Richmond (now part of Virginia Commonwealth University).

In March 1865.

Oh-ho! Now we’re having fun: did our man attend medical school while still a soldier and patient/hospital aide in 1864-5?

That would be unusual.

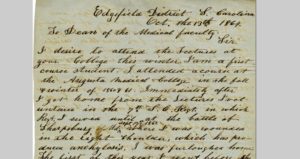

Then I got really lucky. Thanks to the digital archives at VCU, I found an October 1864 letter John Rushton wrote to Levin Smith Joines, the Dean of the medical school. In it, he requested admission to the Winter 1864-65 course, noted he’d had previous training in Georgia 1860-61, and best of all, described what he’d been doing since Sharpsburg.

So, in contrast to the tale of the CSRs, it turns out he was furloughed home after he was wounded in the shoulder at Sharpsburg and I don’t think he ever returned to his unit. By January 1864 he had been judged disabled and was teaching school in Edgefield, SC.

He was admitted to the Medical College for the 1864-65 winter session and graduated in 1865. The day after he’d been “retired” in the Army records, coincidentally.

Long story short – I got to see part of the man’s story in his own hand, in real time. Rare, but very gratifying. And a lot more exciting than the basic and sometimes confused service records.

…. on to the next story.

Lieutenant Anthony Morin

4 April 2020

James Grant of the Christian Commission was on the field after the battle of Antietam …

While moving around amongst the wounded … my attention was called by a disabled officer to a friend of his, badly wounded in the face, and lying out somewhere without a covering. Following his directions, and throwing the rays of my lantern towards the foot of a wooden fence, I soon discovered the object of my search … The ball had entered one side of the cheek and passed out at the other, grazing his tongue, and carrying away several of his teeth. His face was horribly swollen, and he could not speak. On asking him if he was Lieut. M. [Morin], of Philadelphia, he assented by a nod of his head.

During the next two days, the Surgeons were all so busy, that his wound, which had been hurriedly dressed on the field, remained untouched; yet he showed no signs of impatience. In the inflamed, wounded condition of his mouth, nothing could be passed down his throat. On the third day, as the Surgeons still had more to do than they could manage … [w]ith some hesitation, I took the Lieutenant’s case in hand, and, after two hours’ labor, succeeded in cutting away his whiskers and washing the wound pretty thoroughly, both inside and outside the mouth. This done, and all the clotted blood and matter cleared away, the swelling abated, and he began to articulate a little. A day or so afterward, he could swallow liquids; and being carefully washed daily, in less than a week he was able to travel to Philadelphia …

__________________

Notes

This excellent photograph of First Lieutenant Anthony Morin of Company D, 90th Pennsylvania Infantry is from the collection of Scott Hann.

The quotes here from Edward P. Smith’s Incidents among Shot and Shell (1868), online from the Hathi Trust.