Charles Leiper of Rush’s Lancers

1 April 2020

Here’s an impressive cavalryman you might like to meet: Charles L. Leiper of Rush’s Lancers – the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Although cavalry units were not significantly engaged at Antietam on 17 September, they battled all across Maryland in the week or so before.

On the 7th [September 1862], Lieutenant Charles L. Leiper was placed in command of Company ‘A,’ which he retained until the beginning of October. On the march to Antietam, when near Frederick, Maryland, on the 13th of September, he came upon a body of dismounted rebel cavalry in a wood. Although largely outnumbering his small force, he drove them in confusion, and made some prisoners. The enemy were armed with carbines, and though our men had only the lance and their pistols, by one determined charge they succeeded in dislodging the enemy, who fled in dismay.

This was Leiper’s habit through the war – taking aggressive action apparently without regard for the odds or his own safety.

He was seriously wounded twice as a result, and was promoted to Captain, Major, Lieutenant Colonel, and Colonel of his regiment by early 1865, and had been their commanding officer in practice since mid-1864. In March 1865 he was breveted – honorarily ranked – Brigadier General of Volunteers for his service.

Amazingly, he was then just 22 years old.

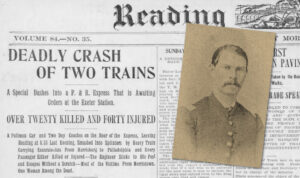

Deadly crash of two trains

23 March 2020

Corporal John H “Highly” Coulston, Company A, 51st Pennsylvania Infantry was wounded at Fox’s Gap on South Mountain in September 1862. He was Captain by January 1865 and mustered out in July.

Tragically, he was severely injured in a train crash – known afterwards as the Exeter Station wreck – on 12 May 1899 while returning with many other veterans from the dedication of a statue of statue of General Hartranft in Harrisburg. He died the next day.

Superimposed on the front page of the Reading Times of 13 May 1899 above is a picture of him c. 1864 from a published photograph contributed to his Findagrave memorial by Charles McDonald.

The crushed train car below testifies to the force of the collision. Below that is a post-war photograph of Isaac E Filman – also of Company A and wounded at Fox’s Gap, and also killed in the crash (lower two photos from the Pottstown Mercury of 1 July 2012).

Crapsey and the Bucktails in Maryland

13 March 2020

Sergeant Angelo M Crapsey of the “Bucktails” – the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves. Eyewitness to the Maryland Campaign.

After fighting at Turner’s Gap on South Mountain on 14 September he wrote a friend at home:

… It looked like a task to storm the mountain for it was very steep and more than one mile to the top of it. In we went. Company I was reserve awhile & the Rebels shelled us, wounding 3 of our men, 2 of which died that night. My right hand man was one to fall. Soon after this we were deployed & 3 with me were posted behind a rock wall. W Brewer & L Bard & Hero Bloom [Blom] were with me. The Rebels were behind a fence and rocks. Bard was wounded and Brewer helped him away & soon Bloom was shot by my side. He died that night. Northrop fell a few yards to the left. Maxson fell dead within a few feet of him.

Well it was close work. I only got my face and eyes full of bark for there was a tree just on the rock. That’s all of this …

Two days later, on the evening of the 16th, he and the Bucktails were at Antietam:

… Just as we emerged from a belt of woods into a plowed field, the Rebels fired across the field. We moved forward double quick & lie down behind a little knoll & commenced firing at the Rebels … It was soon dark. We kept firing so fast they could not stand it. My gun [a Sharps breechloader] was so hot I was afraid to load it but kept stuffing it and firing at the flash of their guns. We charged & drove them out of the woods … Col. McNeil was killed and Lt Ellison [Allison] also. I fired 70 times & was well satisfied to stop for the night.

(you can find something about all those names from the Bucktails’ page on AotW)

Crapsey was captured at Fredericksburg in December, was a prisoner at Libby in Richmond, was released and saw action again at Gettysburg, but was very ill afterward and was discharged for disability in October 1863.

He went home probably suffering from PTSD and attempted suicide twice. He succeeded in killing himself the third time, with a friend’s rifle, in August 1864. He was 21 years old.

________

His picture from a photograph posted on Crapsey’s Findagrave page by Dennis Brandt, author of Pathway to Hell: A Tragedy of the American Civil War (U of Nebraska Press, 2008) – the tragedy was Crapsey.