Surgeon and Major William James Harrison White, USA

7 January 2020

Washington, DC-born William J.H. White was 35 years old in September 1862 and had been an Army doctor since he graduated from the Columbian College Medical School (now George Washington University) in 1849. At least 10 of his 13 years service had been in the frontier West, with the 2nd US Cavalry in Texas and New Mexico. His had not been soft duty.

Earlier in 1862 he had seen considerable action with the 6th Corps and gained experience with large numbers of casualties, notably at Gaines’ Mill in June and Bull Run in August.

He arrived with his Corps at the battlefield of Antietam about 10am on Wednesday, 17 September and his job as Medical Director was to set up and staff the Corps field hospital; the battle had been underway for some 5 hours when he arrived, which made his work both important and urgent. He established a hospital on the Michael Miller farm, known later as the Brick House Hospital, and nearby at Dunbar’s Mills, both at the north end of the East Woods. He probably didn’t treat any soldiers himself, but would have been closely involved with their care.

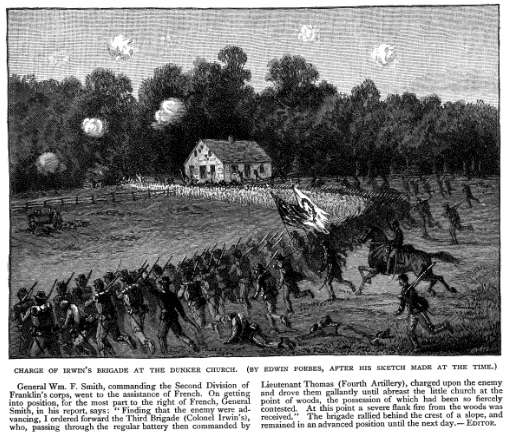

The troops of his 6th Army Corps were placed largely in holding and supporting positions on the field at Antietam, but one Brigade, Irwin’s of Smith’s 2nd Division, made an attack toward the West Woods about mid-day.

That afternoon something went terribly wrong with Dr. William White.

During the whole of the terrible battle of Wednesday Dr. WHITE was superintending the care and removal of the wounded from the battle; and it is supposed the excitement consequent to the occasion produced a species of temporary insanity, for after the battle had lulled somewhat, he rode up to Gen. FRANKLIN and said, “General, if you will give me a regiment of men I will clear those woods of rebels,” pointing to a piece of woods on his right in which was stationed a very large force of rebels.

Gen. FRANKLIN replied, that fifty regiments would be unable to dislodge the enemy from the position, and that it would be useless to attempt the experiment. Dr. WHITE rejoined, “If you will not give me the men to take those woods, I will go and take them myself,” at the same time proceeding in the direction of the place where the rebels were concealed, at a rapid gait. When within about twenty or thirty rods of the edge of the wood, he was fired upon by several rebel sharpshooters, two balls taking effect, one in the forehead and another in the breast, killing him instantly.

_________________________

Edwin Forbes’ engraving of Irwin’s attack is from the Century Magazine of June 1886.

The extraordinary narrative of his death quoted here is from a Memorial of 20 September issued by US Army Surgeon-General William A. Hammond and published in the New York Times of 12 October 1862.

This story also cross-posted to CivilWar Talk.

Ben Witcher’s Story

26 June 2019

The map above is centered on the eastern part of the Miller Cornfield near the East Woods at Sharpsburg on the morning of 17 September 1862. There has been heavy fighting here since dawn and, along with other regiments in action, the 6th Georgia Infantry has been nearly wiped out. It is between 8 and 9 in the morning.

Stephen Sears, in his classic Antietam book Landscape Turned Red (1983), wrote this dramatic vignette of that time and place:

Private B. H. Witcher of the 6th Georgia urged a comrade to stand fast with him, pointing to the neatly aligned ranks still lying to their right and left. They were all dead men, his companion yelled at him, and to prove it he fired a shot into a man on the ground a few yards away; the body did not twitch. Private Witcher was convinced and joined the retreat.

Over the years since I first read it, I had forgotten Benjamin Witcher’s name, but not that story. Who could forget that imagery? Even in combat, the shock of shooting into one of your own mess-mates would have been horrendous.

At least three other well-known books on the battle have used this anecdote, too, citing Landscape as their source. If you’ve read any of the basic literature, then, you will have seen it, and you’d remember.

But I’ve just found it isn’t true. It didn’t happen that way.

This lovely piece is a decorative military record – “very tastefully printed in 10 colors” – for Private Samuel Wilson Evans of the 12th Pennsylvania Reserves. He served from 1861 to 1864 and saw action at South Mountain on 14 September and at Antietam on 17 September 1862.

This certificate was produced by the Army and Navy Record Company, which was started in about 1883 by Walter C. Strickler (c. 1837-after 1920) of Philadelphia – an outgrowth of his personal project to gather an exhaustive timeline for every Union military unit and action of the Civil War. Strickler’s son Theodore compiled some of that work in When and Where we Met Each Other on Shore and Afloat … (1899).

The colorful parts of this decorative record were printed, but Evans’ name and service details are hand-written. It was “presented” in his name to his wife Sarah Jane and daughters Margaret, Nellie May, and Mary Belle on 1 October 1905. The original is about 19×27 inches and it’s online thanks to the Maryland State Archives.

Below is an advertisement in the National Tribune of 5 October 1905. By that time the National Tribune had bought out Strickler, and was offering these certificates on their own. Strickler and the Tribune had been in a marketing relationship for some years before.