Following General French

18 September 2006

Last month Fred Ray posted some interesting discussion on the question of why French swung his division south into the Sunken Road, rather than pushing more westerly, directly behind Sedgwick at Antietam.

These two generals led divisions in Edwin Sumner’s Federal Second (II) Corps on the Maryland Campaign. Brigadier General John Sedgwick, with “Bull” Sumner in the van, crossed the Antietam over the upper bridge, and at Pry’s ford just downstream, between 7:30 and 8 o’clock in the morning of 17 September 1862. BGen William French crossed his men at the ford 15 or 20 minutes behind Sedgwick.

… the division, marching in three columns of brigades, Max Weber on the left, the new regiments in the center, and Kimball’s brigade on the right. When my left flank had cleared the ford a mile, the division faced to the left, forming three lines of battle adjacent to and contiguous with Sedgwick’s, and immediately moved to the front …

(BGen French, from his Report)

Carman has Sedgwick slightly in advance of French at point “a” on the map by about 8:30 am. I believe that’s the spot where French says he faced left and formed lines. It would have been the last place he would have been likely to actually see Sedgewick, if, in fact he was even in contact at that point.

I drove and walked the ground from the East Woods, through that spot, to the Upper Bridge and near Pry’s Ford Saturday afternoon. I’d never been up that way before. What an eye-opener.

Captain Lewis and friends in high places

7 September 2006

Doing research into the people and events of the Maryland Campaign is often a game of large effort invested for little return. In some cases, though, the reverse is true, and the clues revealed can be a bit overwhelming.

One such case is a story I’ve been working on and off for about a year now. It centers on Captain Enoch E. Lewis, Company K, 71st Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers. Or maybe it centers on President Lincoln, I’m not sure yet. All I have right now is a collection of hints and pointers to interesting relationships and events.

The bare bones are these:

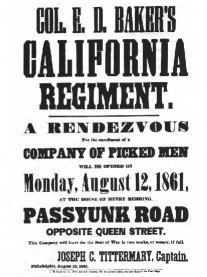

Lewis, a young lawyer of privileged background, of Philadelphia society, joined Oregon Senator Edward Baker‘s famed ‘California Regiment’ in 1861 as Captain of Company K. He served bravely in action through the battle of Antietam (September 1862), where he briefly succeeded to command of the regiment as senior officer present.

There is significant evidence that he and (by then) Major R. Penn Smith, another Philadelphia dandy who was the regiment’s first Adjutant, had clashed personally and professionally. Was it a long-standing feud? Slights given and received while in service? Perhaps both, I can’t tell yet.

Following Antietam, Captain Lewis was reported absent and shortly afterward charged–presumably by Major Smith– then arrested and court-martialled for being absent without permission and conduct ‘unbecoming an officer’ and ‘prejudicial to good order and discipline’.

Sumner as Queeg?

30 August 2006

This post properly belongs as a comment on Dimitri Rotov’s blog, which doesn’t offer that facility.

I’ve been following Dimitri’s series on the appointments of McClellan’s Corps commanders. Intriguing material, though I confess I’m not sure what most of it means. Probably because I lack the background in the more subtle political machinations within the Lincoln Administration. I’m learning.

Yesterday, I read his related piece called Sumner, McClellan, Johnston, and Davis which deals with the relationship(s) between George McClellan and Edwin Sumner.

At the time of the Crimean War, Edwin V. Sumner was the commander of the First U.S. Cavalry Regiment. Joe Johnston was his lieutenant colonel and George McClellan one of his captains (i.e. squadron commanders).

Dimitri notes that Johnston thought very little of Sumner, and was convinced the old fool had it all wrong when it came to the new Cavalry arm and managing his Regiment. So Johnston suggests McClellan–then on the Commission to the Crimean War–work up doctrine for how US Cavalry should be run, and feed it to the War Department. McClellan having the ear of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

Someone must save the Cavalry from Sumner, but McClellan and Johnston are disappointed in their quest.

Davis, says Dimitri,

… foreshadowing the typology of stubborness that has become an ACW cliche, refused to be moved by McClellan’s overtures. Sumner would remain undisturbed by new thinking.

… Odd to think that Sumner was, in his way, the root cause of McClellan’s resignation.

So there you have it. Sumner the mismanaging, bumbling old man; Davis too stubborn to recognize the Future; Johnston the instigator; and McClellan, Army visionary, becomes the victim, after trying to do the right thing.

As I read Dimitri’s post, though, quite a different image jumped to my mind.

still from the Caine Mutiny, 1954

[plot summary]

Yes, I know it’s only a movie.