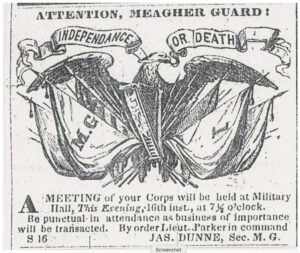

Attention, Meagher Guard! (1853)

7 March 2021

I’m exploring another Irish unit today – Company K of the First South Carolina Infantry (McCreary’s). Formed in June 1861 as the Irish Volunteers for the War, they came largely from a pre-war militia company organized in Charleston in about 1853: the Meagher Guards.

When the Guards’ idol and namesake Thomas F. Meagher began recruiting Irishmen for the Union in New York in 1861

the Charleston company condemned Meagher for “taking arms against us in this most unholy war in support of usurpation and oppression,” struck his name off their roll of honorary members, and on 9 May changed the unit’s name to Emerald Light Infantry.

Two former officers the Meagher Guard who formed the Irish Volunteers for the War – Company K – were wounded at Sharpsburg in September 1862:

Dublin-born Captain Michael P. Parker was a carpenter who “had acquired an education beyond his circumstances. He was an able mathematician, and an excellent writer.” Formerly First Lieutenant of the Meagher Guards, he was made Captain of Company K in January 1862. He was “dreadfully” wounded at Sharpsburg, and never really recovered, dying young at about age 35 in 1868.

First Lieutenant James Armstrong, Jr. was only slightly hurt at Sharpsburg and was eventually promoted to Captain of the Company after Parker. He was born in Philadelphia of immigrant parents but was raised in Charleston and lived for some time in Ireland in the 1850s.

At least 9 more men of Company K were casualties on the Maryland Campaign and many had probably been members of the Meagher Guard; with Irish surnames like Burns, Dillon, Feeney, Holloran, Kennedy, and Sullivan.

The announcement for the Guards, above, is from the Charleston Daily Courier of 16 September 1853. I found it and the quotes above in the excellent Meagher Guard, Charleston’s Fighting Irish by Bill Bynum, published in Company Front (Issue 1, 2011) [pdf], the journal of The Society for the Preservation of the 26th Regiment North Carolina Troops.

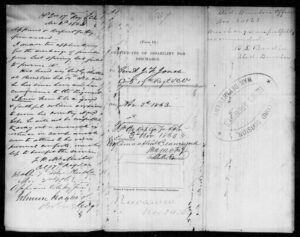

Approved and respectfully forwarded

23 February 2021

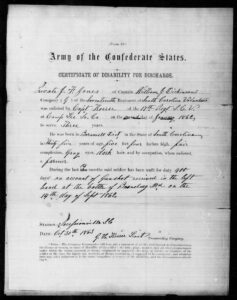

This is the outside of a 30 October 1863 application submitted by Lieutenant George H Kearse, then commanding Company G of the 17th South Carolina Infantry, concerning Private Jones Frank Jones of his Company. Jones had been wounded by a buckshot through his left hand at Turner’s Gap on South Mountain on 14 September 1862, 14 months before.

It was the second or third such application for discharge made on his behalf.

Regimental commander Colonel Fitz William McMaster passed it along with the following illuminating note:

Hd Qr 17th Reg S.C.

Nov 2nd 1863Approved and respectfully forwarded –

I made two applications for the discharge of Private Jones last Spring but failed to procure it.

His hand was badly mutilated at Boonsboro Sep 14th 1862 and he has since been an inconvenience to the Regiment. I know him to be a good & faithful soldier anxious to serve his country and hope he will not be compelled to ___ [?] out a miserable existence in camp unable even to attend to his own personal comforts, much less to benefit the service.

F.W. McMaster

Col 17th Reg S.C.

Private Jones was discharged 3 days later.

The inside of the application is shown below. It’s from Jones’ Compiled Service Record at the National Archives.

The 34 star US National flag

29 January 2021

These are the national colors of the 30th New York Infantry regiment, probably carried at Antietam, from the New York State Military Museum.

Appropriately, the flag has the 34 stars in the blue canton, following the Act of April 4, 1818 signed by President Monroe, which provided that the American flag should have 13 stripes, and one star for each state; new stars to be added to the flag on the 4th of July following the admission of each new state.

A 33-star flag was in use from 1858 to 1861 and the 34-star flag became official on 4 July 1861, a star added for the admission of Kansas (29 January 1861). It was in use for 2 years until 4 July 1863, when a 35th star was added for West Virginia (admitted 20 June 1863).

While probably most common, the rectangular 34-star arrangement above – similar to our modern 50-star pattern, but in rows of 6-5-6-6-5-6 – was not the only one used, as the Act specified only the number of stars. Also frequently seen are flags with rows of 7-7-6-7-7 stars and similar.

Here’s a display flag with quite another design. This particular one was made to be hung on a wall and is only finished on one side (as seen on PBSs Antiques Roadshow in 2016).

Here’s a variation of that circular arrangement, sometimes called the Great Medallion pattern, on a flag sold by Heritage Auctions in February 2007.

Flags were also made with the stars formed in the shape of a large star or flower, such as this one, sold by Heritage Auctions in May 2010.

Let me know of other historical 34-star flags you’ve seen, won’t you?