From Antietam to the Arctic: A.W. Greely

20 August 2018

Adolphus Greely was only 18 years old but already a veteran of more than a year’s Army service by the time he was wounded in the face in combat in or near the West Woods at Antietam on the morning of 17 September 1862. He was a Corporal in Company B, 19th Massachusetts Infantry.

Before the War he’d been working as a jeweler in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and was eager to find a bigger place in the world for himself. The Army gave him a chance to do just that.

Twenty years after Antietam he was leading a scientific observation team near the North Pole, and a year after that he was in very great danger of dying there …

Apparently Greely was born to be a soldier – he was very good at it from the start.

In November 1862, after he recovered from his Antietam wound, he was promoted to First Sergeant of his Company. In March 1863 he was discharged from the 19th Massachusetts to take a commission as 2nd Lieutenant in the new 9th Regiment, Corps d’Afrique – later designated the 81st US Colored Infantry and afterward reorganized as the 77th United States Colored Troops. He served with them principally on garrison duty at Port Hudson on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, originally in Company B, but later transferred to “I”, and finally “F”. He was promoted to First Lieutenant on 14 April 1864 and Captain on 26 March 1865. He was honored for his War service by brevet to Major, US Volunteers on 13 March 1865 and mustered out 22 March 1867.

The War was over, but he remained in uniform, being commissioned 2nd Lieutenant, 36th US Infantry to date from 7 March 1867. He transferred to the 5th US Cavalry after the 36th Infantry was disestablished in 1869. He was frequently detached for service with the Signal Corps as Acting Signal Officer (ASO), building telegraph lines in the West and learning about telegraphy, electricity, and meteorology in the process. He was promoted to First Lieutenant on 27 May 1873.

What he’s really famous for, however, is commanding the 1881 Lady Franklin Bay Expedition, an initiative of the First International Polar Year to establish a research station at what became Fort Conger on Lady Franklin Bay, Ellesmere Island, in the north-eastern-most part of Canada. His team of 24 men were mostly soldiers, along with a physician and 2 Inuit hunters.

The first year of the expedition went very well – the team was delivered by the steamer Proteus from St. Johns, Newfoundland to their new home at Ft. Conger, Lady Franklin Bay, on the northeastern coast of Ellesmere Island without significant issue in late summer 1881. The Proteus returned south leaving them without a way home, but there were to be relief expeditions sent each of the next two summers with supplies for the group.

For 23 months Greely and his men were active in collecting meteorological, tidal, magnetic, astronomic, and other physical data from their surroundings, and in documenting the people, plants and animals they found. They also ventured into previously unexplored territory and mapped the new coastlines and other features they found. On one such trip, Lt. Lockwood and Sgt. Brainard reached a new “farthest north” point, getting to about 83° 24′ north latitude – a record that stood for about 20 years before being broken by Robert Peary on his 1898-1902 expedition.

Unfortunately neither the 1882 nor 1883 relief expeditions were able to get through the ice to reach the Greely Expedition, so in August 1883, as per their original instructions, Greely ordered his men to abandon their basecamp at Ft. Conger and led them south by small boat and overland toward a rendezvous point on Littleton Island, on the Greenland shore some 260 miles southeast. They carried their precious observations and data, along with about 40 day’s rations. They expected to find caches of supplies left by the 1882/83 relief ships on Littleton Island, and a better chance of being reached by sea there in the Summer of 1884.

They made it as far as Cape Sabine, an island off the east coast of Ellesmere Island about 200 miles from Ft. Conger before winter fully set in. There they established Camp Clay. They built a crude stone cottage roofed by canvas and their whaleboat, and located small supply caches in the area, but very quickly ran low on food. The hunting was not good and in April 1884 the men began dying of starvation and sickness. One, Private Charles B. Henry (aka Charles Henry Buck, late of the 7th US Cavalry) had been caught stealing from his mates and after repeated incidents Greely had him shot.

A Navy rescue expedition reached them on 22 June 1884, but by then only seven men were still alive. Their rescuers estimated that the survivors would have lasted only a few more days had they not been found. One of their number, Sergeant Joseph Elison, died on 8 July from the effects of frostbite, about 2 weeks after their rescue. The other six surviving members of the team posed for a photograph on USS Thetis on 2 or 3 July 1884.

[22. First Lieutenant Adolphus W. Greely; 23. Private Julius Frederick; 24. Sergeant David L. Brainard; 25. Private Henry Bierderbick; 26. Private Maurice Connell; 27. Private Francis Long.]

Once back home, Greely had to defend himself on a couple of points. For having Private Henry executed, which was deemed reasonable and necessary, but also because some of the team’s dead bodies had flesh removed, suggesting cannibalism among his men. To this he replied that he had certainly not ordered or condoned such activity, and did not have knowledge of it.

Generally, though, the survivors were treated as heroes, and two years later, 13 years after his last promotion, Adolphus Greely was appointed Captain (11 June 1886). Soon after, however, his career took a huge leap. In December he was made acting Chief Signal Officer in Washington DC, due to General William B. Hazen’s illness, and was appointed Brigadier General, and Chief Signal Officer, USA on Hazen’s death in January 1887.

He presided over a growing and increasingly sophisticated Signal Corps for the next 20 years, noted for introducing technologies such as telephones, automobiles, and radiotelegraphy, and for guiding the Signal Service through the Spanish-American War era. He was promoted to Major General in 1906, and retired at that rank in March 1908 after 47 years in uniform.

He had been a founding member of the National Geographic Society in 1888, and after retirement he continued to write and speak on the topic of arctic exploration.

On his 91st birthday, 27 March 1935, he was presented with the Medal of Honor, awarded by a special act of Congress for his lifetime of service. To date it’s one of only two such awards for non-combat service (the other was to Charles Lindberg in 1927 for his trans-Atlantic flight).

General Greely died at his home in Washington D.C. in October 1935, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

___________________

Notes

Adolphus W. Greely’s bio page and Medal of Honor citation are on AotW.

The picture at the top is of one of four postage stamps honoring Arctic explorers (Elisha Kent Kane, Adolphus W. Greely, Robert E. Peary and Matthew Henson, and Vilhjalmur Stefansson) issued by the US Postal Service on 28 May 1986. Image from Linn’s Stamp News.

Greely’s military career dates are found in Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in the Civil War (Volumes 2 and 7, 1931-35), from the Massachusetts Adjutant General, and in Heitman’s Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army (Volume 1, 1903).

The group photograph of the Army expedition members was taken in Newburyport, MA in 1881. From a print in the Relic Collection of J. S. Reigart (1836-?), exhibited at the Vancouver Rare Book, Photograph & Paper Show [online]. A later edition (and published etchings from it), had missing members pasted in.

Front row (L-R): Pvt. Maurice Connell, Sgt. David L. Brainard, 2Lt. Frederick F. Kislingbury, 1Lt. Adolphus W. Greely, 2Lt. James B. Lockwood, Sgt. Edward Israel, Sgt. Winfield S. Jewell, Sgt. George W. Rice. Back: Pvt. William Whisler, Unknown (replaced by Pvt. William Ellis), Pvt. Jacob Bender, Sgt. William H. Cross, Pvt. Julius Frederick, Sgt. David Linn, Pvt. Henry Biederbick, Pvt. Charles B. Henry (aka Charles H. Buck), Pvt. Francis Long, Unknown (replaced by Pvt. David Ralston), Corp. Nicholas Salor, Sgt. Hampden S. Gardiner, Sgt. Joseph Elison. Not shown: Dr. Octave P. Pavy, “Eskimo†Jens Edward, “Eskimo” Frederick Thorlip Christiansen.

See more about these men on a biography page from Ft. Conger at virtualmuseum.ca.

The engraving of their house at Ft. Conger is found as the frontpiece in the first volume of Greely’s Report on the Proceedings of the United States Expedition to Lady Franklin Bay … (1885, pub. 1888); both volumes are online from the Hathi Trust.

Fort Conger was named for U.S. Senator Omar D. Conger who was one of the few supporters of the expedition.

The picture of the Expedition survivors is part of a larger photograph from the US Naval History and Heritage Command.

Greely’s public response to Private Henry’s execution and charges of cannibalism are in a New York Times article of 14 August 1884.

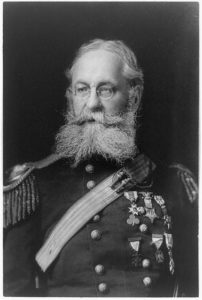

The half-length portrait of him in dress uniform was taken after 1890, and is from the Library of Congress.

The final photograph here is of Greely receiving the Medal of Honor from Secretary of War George Dern in Washington in 1935, also from the library of Congress.

For much more about Greely and his Expedition, you might like to try these resources:

The two volumes of Greely’s “popular” history Three years of Arctic Service (1886), online.

Disaster at Franklin Bay by Andrew C.A. Jampoler in Naval History Magazine (August 2010) from the Naval Institute.

Notes about Sergeant Brainard and his papers at the Dartmouth Library.

Fire & Ice: Adolphus W. Greely from the Army Heritage Center Foundation.

Rebecca Robbins Raines’ Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the Signal Corps (US Army, Center for Military History, 1999).

A photograph of a Diaorama of the Greely Expedition, at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, showing Lt. A.W. Greely, U.S. Army, welcoming Lt. Lockwood and Sgt. Brainard back to Ft. Conger (after their record “northern-most” trek), Library of Congress.

September 17th, 2018 at 8:50 pm

I find great resonance in your last three blog entries: Like Jerry Kingsbury, I too am the descendant of an Antietam veteran. I am not nearly so remarkably close as her, of course. Like A. W. Greeley, my great-great-grandfather served with Massachusetts Infantry… and was injured in the face… in the West Woods. Woah. Private A. W. Davis’ temporary grave in Hagerstown is documented in your June entry. I made inquiries in Hagerstown last year, but my question went unanswered then. I was just a few short blocks from the site. Keep up the Good Work.

September 18th, 2018 at 11:10 am

Thanks Tim!