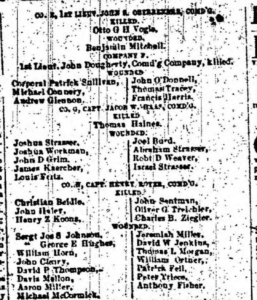

Crampton’s Gap casualty list, 96th Pennsylvania Infantry

31 August 2024

Appended to Colonel Cake’s official report as printed on page 2 of the Pottsville (PA) Miner’s Journal of Saturday, 4 October 1862, is his list of the men of his 96th Pennsylvania Infantry who were killed or wounded in the fight at Crampton’s Gap on South Mountain on 14 September 1862. It’s not found in the Official Records in company with the Colonel’s report.

My transcription of the text and links to the individual soldiers’ pages on AotW, after the jump …

Maryes in Maryland

8 April 2024

Here’s Lieutenant Edward A. Marye‘s (probably pronounced “Mary”) family home in Fredericksburg, VA as it looked in May 1864, then in use as a Union military hospital for troops wounded during the battle of the Wilderness.

First Lieutenant E.A. Marye (1862)

His father John Lawrence Marye (1798-1868), a successful lawyer and mill owner, bought land and a small house on a hill overlooking Fredericksburg in about 1824. He improved the house and named it Brompton, after the Middlesex village in England from which his Hugenot-Norman great-grandfather Rev. James Marye (or Jacques Marie, 1692-1768) came to America in about 1730.

The high ground around it became known as Marye’s Heights – now famous for the combat there in December 1862.

Lt. Edward Marye commanded a section of 2 3-inch Ordnance rifles of the Fredericksburg Artillery (Brig. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Division) at Harpers Ferry (14-16 September) and Shepherdstown (19 September), and led the battery at least part of the day at Sharpsburg (17 September) while Captain Carter M Braxton acted as Hill’s chief of artillery.

But there were also 4 other Maryes in the battery …

Private Alfred James Marye, Edward’s nephew, was on the Maryland Campaign and was wounded by counter-battery fire at Boteler’s Ford on the Potomac on 19 September. He was barely 16 years old. He served with the battery to the end of the war and was afterward a railroad clerk in Montgomery County, VA.

Private Alexander Stuart Marye (1841-1915), a younger brother of Edward’s, enlisted in the battery in June 1862 and was probably in Maryland in September. He was on detail away from his unit on ordnance and administrative duties for most of the rest of the war and was surrendered and paroled at Greensboro, NC in May 1865.

John Lawrence Marye, Jr. (1823-1902), also Edward’s brother, enlisted as a Private in April 1861 and was promoted to 5th Sergeant in April 1862. He was absent, sick into October 1862, so probably not in Maryland, but was surrendered and paroled with the battery at Appomattox Court House, VA on 9 April 1865. During the war he also served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1863-65). He’d been a wealthy lawyer and farmer in his own right before the war, and Mayor of Fredericksburg in 1853-54. He was afterward again a Delegate (to 1868) and Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1870-74).

Another of Edward’s nephews, his oldest brother James’ son Private William Nelson Marye (1841-1929) enlisted in Braxton’s Mounted Artillery (later Fredericksburg Light) on 12 May 1861, but was detached from his unit for much of 1862 and probably not with them in Maryland. He was with the battery from March 1863 to September 1864, when he was again detailed, as a clerk to a military court for the 3rd Army Corps, but was back by Appomattox in April 1865.

To complete Edward’s story: he was promoted to Captain and it became his battery in March 1863, but he did not survive the war; he died of disease in Petersburg, VA in October 1864.

Notes

The photograph above of the Marye house “Brompton” is from the Library of Congress.

Details about Brompton from its National Register of Historic Places nomination form [pdf]. The home was acquired by Mary Washington College (now University) in 1947 and it is now their president’s residence.

Lieutenant Edward Marye’s picture here is an ambrotype in the collection of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond.

The Maryes’ military records are found in the US War Department’s Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers, Record Group No. 109, Washington DC: US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Twelve hundred pounds of corn

18 March 2024

While going through documents in Captain Robert Boyce‘s Consolidated Service Record (CSR) jacket, I came upon this receipt dated “Camp in the field Sept 23d 1862.”

My transcription:

Rec’d of Capt C. McRae Selph aſs [asst] Quartermaster C.S.A. the following articles viz –

Sept 12th 1200# Twelve hundred pounds of corn.

” 13th 1170# Eleven hundred + Seventy pounds of corn.

” 14th 1120# Eleven hundred + Twenty ” of corn.R. Boyce

Capt Lt Battery

Boyce commanded a six-gun battery of the Macbeth Light Artillery on the Maryland Campaign of 1862. The corn was likely forage for his horses. How many horses? A back of the envelope calculation, and I’m no expert …

Minimum 4 horses each for 12 limbers (6 guns, 6 caissons), forge wagon (total 52); Minimum 16 personal horses for Captain, 4 Lieutenants, 8 Sergeants, 2 buglers, 1 guidon; (?) spare horses; total at least 70 horses.

The receipt jumped out because it is the first I’ve seen for forage delivered to a unit while on combat service in Maryland. All sorts of research questions follow, like:

– How many army wagons did it take to haul that grain to Boyce?

– How far did those wagons travel? From Winchester, maybe?

– How long would that much grain have lasted? Assuming about 12 pounds per horse/day (or twice that if no hay) and at least 70 horses, not long.

– How much grain or other forage would all the horses of the Army of Northern Virginia have required? Were they getting it in September 1862?

– Horses cannot long live on grain alone. Was there good pasturage in Maryland? Hay was probably too bulky to transport to the combat zone.

I’d be glad to hear from logistic experts on this.