Hospital lists after Antietam

4 February 2024

On 12 October 1862 the New York Times printed lists of soldiers who died at several field hospitals near the battlefield in the 2 weeks immediately after Antietam. They contain some excellent detail I’ve not seen elsewhere, and I’m saving them here [PDF] for current and future reference.

Another in a series.

Francis Effingham Pinto was in the grain storage and transport business in Brooklyn before and after the Civil War. He had been successful as a merchant since about 1850, when he decided to sell supplies to ’49ers in California rather than mining gold himself.

He was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the 32nd New York Infantry in May 1861 and on 13 September 1862 was temporarily assigned to command their sister regiment, the 31st New York Infantry as they approached South Mountain in Maryland – the 31st having no field officers (Colonel, Lt. Colonel, Major) of their own present.

He was in command of the 31st at Crampton’s Gap on the 14th and at Antietam on 17 September, but did he also lead the 32nd New York Infantry at Antietam?

The New York State monument (1919) on the battlefield lists Colonel Roderick N Matheson and Major George F Lemon (both also longtime Californians) in command of the 32nd at Antietam. They certainly led the regiment in action at Crampton’s Gap on 14 September, but both were mortally wounded there and obviously not at Antietam 3 days later.

Lieutenant Colonel Pinto’s cemetery biography suggests he took charge of both units at Antietam. The definitive answer is probably in Pinto’s own History of the 32nd Regiment, New York Volunteers, in the Civil War, 1861-1863, and personal recollection during that period, which he published in 1895, but I’ve not found a copy yet.*

Returning to Pinto’s civilian life after the war, here’s a lovely illustration of a floating grain elevator and F.E. Pinto’s grain storage buildings in Atlantic Basin, Brooklyn, NY in 1871.

Notes

Colonel Pinto’s photograph is from the MOLLUS Massachusetts album, online from the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks.

The picture of Pinto’s stores in Brooklyn is from Harper’s Weekly of 20 May 1871 and was shared online by Maggie Land Blanck.

* Update

As Dave Henry notes in his comment below, Harry Smeltzer found a typescript copy of Pinto’s History and has kindly posted it [pdf] on Bull Runnings. In it, Pinto says

On the morning of the 17th … [a] committee of officers from my old regiment, the 32nd N.Y., went to Gen. Newton and requested him to send me back to the 32nd Regt, Col. Matheson and Major Lamon having been wounded at Crampton’s Gap. The Regt. was without a field officer. He assented to their wishes, and I unexpectedly received orders to join my gallant old Regiment. This change left the 31st Regt. under the command of their Major, which was not pleasant to the officers.

The charge of the 7th Maine at Antietam

10 February 2023

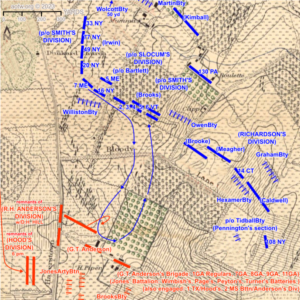

One of the saddest stories of Antietam is that of the vain heroism of the men of the 7th Maine Infantry on the Piper Farm at about 5 pm on 17 September 1862. Their ill-considered charge there destroyed the regiment as a fighting force and obtained little result.

[Battle Map #15 on AotW]

Their commander, Major Thomas Worcester Hyde of Bath, Maine, described it in his after-action report 2 days after the battle and refined his narrative in his later memoir Following the Greek Cross, or, Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (1894), which I’m excerpting here to accompany a new battle map on AotW.

Colonel Irvin [William H Irwin] of the 49th Pennsylvania commanded our brigade at Antietam. He was a soldier of the Mexican War, and had been wounded at Resaca de la Palma. He was a gallant man, but drank too much, of which I was then unaware.

read the rest of this entry »