Why the Union Army Did Not Win at Antietam.

10 November 2021

Sergeant Patrick Breen fought with Company C of the 2nd United States Infantry above the Middle Bridge at Antietam on the afternoon of 17 September 1862, and two days later at Boteler’s Ford near Shepherdstown.

Many years later, in 1895, he wrote a piece for the National Tribune – a Washington, DC newspaper which catered to Civil War veterans – suggesting how differently the battle at Antietam would have ended, if only …

Following is a transcription with the accompanying illustrations:

WITHHELD HIS TROOPS.

Why the Union Army Did Not Win at Antietam.

WHOSE FAULT.

A Weak Commander and Autocratic Subordinate.

PORTER’S RESERVE.

A Battle of Which Much was Expected.

By Patrick Breen, First Sergeant, Co. C, 2d U.S.

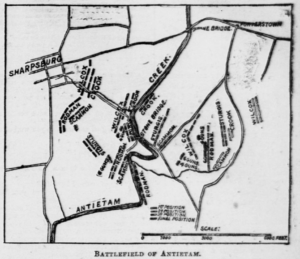

HERE PROBAbly never was a more saddening or sickening sight in the whole war for the Union than that presented in the sunken road and cornfield at Antietam at the close of Sept. 17, 1862. The cornfield lay to the left of the Sharpsburg pike and was distant from the Antietam Creek fully 2,000 yards. Into this field in the early morning the volunteer troops of the Union army charged, only to be met by the Confederate line-of-battle at the point of the bayonet.

The clash came, and was sharp and short. Both lines were nearly totally destroyed, the one by the other. The few so fortunate as to escape retreated on either side for the open ground, the Federals to the sunken road, and then westward across the Sharpsburg pike to the broad, open, plowed field, and the Confederates to the ridge south of the cornfield, where their artillery was posted, there to recuperate and count their loss. From that time on, about 10 a. m. till 1 p. m., that part of the

BATTLEFIELD WAS SILENT.

It was about 12:30 p. m. when the rebel artillery on the ridge began firing on the Second Division, Fifth Corps, which was supporting a 32-pounder Parrott battery in reserve, just behind Antietam Creek, and distant from the rebel battery 2,500 yards. At the same time the rebel infantry advanced through the cornfield once more, and showed itself in force this side of the sunken road, north of the cornfield. The 32-pound Parrotts opened on them, but without

any seeming effect, as elongated shells are fixed, and do not always explode, as in the case of fuse shell.

Then it was that the 2d, 4th, 12th and 14th U. S., with Roberson’s [Robertson’s] light battery, were ordered forward to drive back the advancing enemy.

Down into the Sharpsburg pike and over the Antietam Creek bridge these troops went. At the south end of the bridge the 2d Inf. filed to the left and deployed as skirmishers, the battery moving in front in three sections.

Having reached the sunken road, the enemy in the meantime retiring to the cornfield, amidst a

PERFECT FUSILADE

of grape and canister from the rebel battery on the ridge beyond the Regular regiments moved on.

We soon got down to work and silenced their battery, but at what a sacrifice! The rebel infantry, in the meantime holding the cornfield, kept picking away at us and we at them.

A lull in the contest had came at about 2:30 p. m., with only an occasional picket-shot; then from our left, in the direction of Burnside’s Bridge, a regiment approached in an oblique direction, and moved up for the battery on the ridge. Some would have it that it was one of our New York militia regiments in the gray uniform of that State. Be that as it might, the 2d U. S. gave it a volley, and immediately received one in return, when the battalion immediately dropped to the rear of the rebel battery.

[pg. 2]

This was the field of which great results were expected, hut were not forthcoming or attained at dark of evening, when the contest of arms closed for the day and forever on that field.

The battle was on the Federal side by detail, rather than by the combined force of the army. In fact, at no time was an entire corps of the great Army of the Potomac thrown against the enemy. The Fifth Corps, fully 12,000 strong, was held in reserve behind Antietam Creek, a little to the left of center; Burnside’s Ninth Corps on the extreme left holding the approach to the bridge since named for him.

That it was evident the rebel center was weak was proven by the fact that Capt. Dryer, 4th U. S., had ridden into the enemy’s lines at Sharpsburg, and upon returning had reported there were but one Confederate battery and two regiments of infantry in front of Sharpsburg, connecting the wings of Lee’s army. Dryer was one of the

COOLEST AND BRAVEST

of officers in our service.

Porter and McClellan were informed of what Capt. Dryer had seen, and on McClellan being inclined to forward the now small number of the Fifth Corps in reserve, at this time but 4,000 men, Fitz-John Porter said:

“Remember, General, I command the last reserve of the last army of the the Republic.”

It is needless to say the contemplated move was not executed. Some of us of that field knew of our own observation from the position at the sunken road at the edge of the cornfield that the rebels were weak at that point, and that if prompt orders had been given the Regular regiments then and there engaging the enemy, that his center could be broken, and that by then advancing the reserve of the Fifth Corps in support from the center, and bringing up the Ninth from the left against the rebel right, a different Antietam would be on record to-day, and a drawn battle would not have been the result.

Lee withdrew at his leisure the following day, and no effort was made by McClellan to

STAY HIS PROGRESS

in crossing the broad Potomac.

It was 8 a. m. of the 19th before any effort was made to cross the river in pursuit of Lee, and when the Fifth Corps did cross that morning, not a cavalry-

man or piece of artillery accompanied the three infantry divisions, not even Gen. Porter himself. Not long after planting our feet once more on Virginia’s shores, we discovered, while marching inward from the river, through a deep cut, that the rebels in strong force had lined themselves up on either side of this deep cut, determined that as soon as the Federal troops got well past them they would rise up, fall on our rear, and make the entire Fifth Corps prisoners. But the enemy was discovered by Lovell and Warren in time to frustrate his designs. A halt was made, line-of-battle immediately formed, and falling back on the river with rebel artillery and infantry peppering us, we effected the crossing of the stream a second time within an hour. As we approached the river in our retreat our artillery

CAME TO THE RESCUE

on the hill on the opposite side, and by immediately opening on the enemy over our heads, compelled him to be more careful following us up. While fording the river the corps lost some men in

killed and wounded, all of whom were mostly lost by drowning after being struck by the enemy’s bullets. A new regiment (the Corn Exchange of Philadelphia) having crossed over after the Fifth Corps to the Virginia side, and moving off to the right along the right bank of the Potomac, was captured entire by the rebels. A move on the part of McClellan to again cross the Potomac was not made till the latter part of October, at which time Lee was well up the Valley toward Winchester and over to the southeast toward Manassas. The crossing of the Potomac was made at Harper’s Ferry, and the line of march southward taken up along the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains. To watch the movements of Lee the Army of the Potomac was by divisions and brigades stationed at the many gaps in these mountains for as much as a week and without any shelter was compelled to weather out the bleak winds of early November. Snow caught the army at New Baltimore but a few days before McClellan was relieved by Burnside, which left it in rather a bad plight for the new commander.

That McClellan should allow Lee to get away from him at Antietam was the astonishment of the Army of the Potomac, which, under Little Mac, had been so often foiled by Lee. But it would seem that Fitz-John Porter held a controlling power over the commander of the Army of the Potomac as, for instance, witness his refusal to send forward his 4,000 of reserves at center when Capt. Dryer’s report reached McClellan, and was about to order the move to be made. Herein we have something of the same generalship as was enacted by Gen. Porter toward Gen. Pope on the field of Groveton on the 29th day of the August previous.

_________________

Notes

The complete 18 April 1895 edition of the National Tribune is available online from the Library of Congress.

There are some factual issues with Breen’s proposition: he’s off on the size of the enemy force and the number of guns facing the Regulars in the center of the line that afternoon, and about the number of Fifth Corps troops actually available behind the Middle Bridge to support an attack. And it’s likely the decision to rein-in Captain Dryer came not from Generals Porter and McClellan, but from General Sykes who had a good view of the Confederate defenses from his vantage point high above the east bank of the Antietam.

But, that aside, this article is a good example of many such arguments made in the years after the battle and still used right up to the present.

Breen’s “last reserve of the last army of the Republic” quote attributed to General Porter was originally reported by George W. Smalley in the New York Tribune in September 1862 as “They are the only reserves of the army; they cannot be spared.” In both forms, whether it was ever actually said, it still inspires modern historians.

Please Leave a Reply