Another in a series.

Francis Effingham Pinto was in the grain storage and transport business in Brooklyn before and after the Civil War. He had been successful as a merchant since about 1850, when he decided to sell supplies to ’49ers in California rather than mining gold himself.

He was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the 32nd New York Infantry in May 1861 and on 13 September 1862 was temporarily assigned to command their sister regiment, the 31st New York Infantry as they approached South Mountain in Maryland – the 31st having no field officers (Colonel, Lt. Colonel, Major) of their own present.

He was in command of the 31st at Crampton’s Gap on the 14th and at Antietam on 17 September, but did he also lead the 32nd New York Infantry at Antietam?

The New York State monument (1919) on the battlefield lists Colonel Roderick N Matheson and Major George F Lemon (both also longtime Californians) in command of the 32nd at Antietam. They certainly led the regiment in action at Crampton’s Gap on 14 September, but both were mortally wounded there and obviously not at Antietam 3 days later.

Lieutenant Colonel Pinto’s cemetery biography suggests he took charge of both units at Antietam. The definitive answer is probably in Pinto’s own History of the 32nd Regiment, New York Volunteers, in the Civil War, 1861-1863, and personal recollection during that period, which he published in 1895, but I’ve not found a copy yet.*

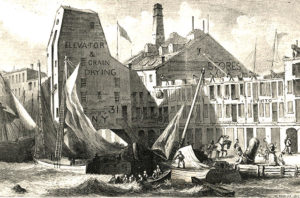

Returning to Pinto’s civilian life after the war, here’s a lovely illustration of a floating grain elevator and F.E. Pinto’s grain storage buildings in Atlantic Basin, Brooklyn, NY in 1871.

Notes

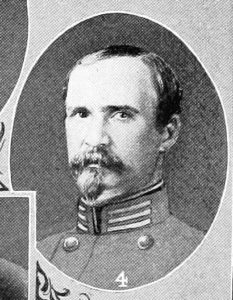

Colonel Pinto’s photograph is from the MOLLUS Massachusetts album, online from the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks.

The picture of Pinto’s stores in Brooklyn is from Harper’s Weekly of 20 May 1871 and was shared online by Maggie Land Blanck.

* Update

As Dave Henry notes in his comment below, Harry Smeltzer found a typescript copy of Pinto’s History and has kindly posted it [pdf] on Bull Runnings. In it, Pinto says

On the morning of the 17th … [a] committee of officers from my old regiment, the 32nd N.Y., went to Gen. Newton and requested him to send me back to the 32nd Regt, Col. Matheson and Major Lamon having been wounded at Crampton’s Gap. The Regt. was without a field officer. He assented to their wishes, and I unexpectedly received orders to join my gallant old Regiment. This change left the 31st Regt. under the command of their Major, which was not pleasant to the officers.

Officers of the US Sixth Corps (May 1862)

4 March 2023

This fine James F. Gibson photograph is now in the collection of the Library of Congress. He took it on 14 May 1862 at Cumberland Landing, VA.

Seated: Col. Joseph J. Bartlett (formerly identified as Andrew A. Humphreys), Henry Slocum, Wm. B. Franklin, Wm. F. Barry and John Newton. Officers standing not indentified. African American child seated in front.

Four of the five identified officers were also at Antietam in September 1862 …

Joseph J. Bartlett – Colonel, 27th New York and commander 2nd Brigade, First Division, Sixth Army Corps at Antietam.

Henry Slocum – former Colonel 27th NY; Major General, USV and commander of the First Division, Sixth Corps at Antietam.

William B. Franklin – Major General, USA and commander of the Sixth Corps at Antietam.

William F Barry – Major, USA and Brigadier General, USV – Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac up to 27 August 1862; he was in the defenses of Washington during the Maryland Campaign.

John Newton – Major, USA and Brigadier General, USV and commander of the 3rd Brigade, First Division, Sixth Corps at Antietam.

USS Monocacy (c. 1890)

3 March 2023

Antietam survivor Martin J. Casey served through the war with Batteries A and B of the First Maryland Light Artillery and soon after, in 1866, enlisted in the US Navy. He served mostly on the Asiatic Station over nearly 25 years, on at least 8 ships, including this one.

She’s sidewheel gunboat USS Monocacy, pictured here in about 1890 “in Chinese waters.” She was named after the 1864 battle near Frederick, MD and was launched in Baltimore soon after it, in December 1864. She had an exceptionally long career in the Pacific, in continuous US Navy commission until sold to a Japanese firm in 1903.

Machinist Casey was scalded – presumably by steam from a burst boiler or line – while aboard Monocacy sometime in the 1870s and bore scars on his abdomen, left arm, and over his left eye afterward. He had a couple of tattoos also, of a dancing girl and a “naval emblem”.

Notes

More about USS Monocacy’s history is online from The Naval History and Heritage Command, source also of the photograph of the ship.

Casey’s service and details like his scarring and tattoos are from enlistment records in Returns of Enlistments of 13 April 1878 (Washington, DC) and 11 June 1887 (Mare Island, CA), online from fold3.

Capt John D Frank, Battery G/1st NY Light Artillery

1 March 2023

This stunning object is the hilt of a highly decorated United States Model of 1850 Foot Officer’s Sword presented by the men of his battery to Captain John Davis Frank in February 1862.

Even more amazing is that the same men were near mutiny just a month or two later due to his abusive treatment of them.

He may have learned that harsh leadership style during his nearly 13 years of pre-war Regular Army service (1848-1861), during which he was promoted from Private to First Sergeant of Battery A, 2nd United States Artillery. Fortunately, he was able to unlearn it with some personal counseling from his Corps Commander Major General Edwin Sumner.

Note

The sword pictured here was sold by Heritage Auctions in 2012 for about $5,000.

Who commanded the 19th Mississippi at Sharpsburg?

27 February 2023

In his invaluable manuscript history of the Maryland Campaign of 1862, General Ezra Carman asserted that Captain Nathaniel W. [H.] Harris commanded the 19th Mississippi Infantry at Sharpsburg on 17 September 1862 and was wounded in action there.

If he had been there he would have been the senior officer present, as all 3 field officers were absent sick or wounded.

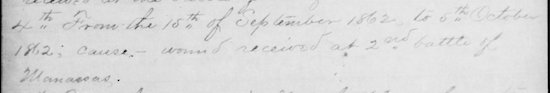

But he was not there. He later wrote that he was absent [f]rom the 15th of September 1862 to 5th October 1862; cause – wound received at 2nd battle of Manassas. It’s not clear where he was from about 30 August to 15 September, but probably not with his unit then, either.

Unfortunately, I’ve not yet found who did, in fact, command the regiment at Sharpsburg.

Here’s Harris’ statement in an extract from the second of a 7 page military resume he submitted on 2 January 1864 at the request of (Anderson’s) Division Headquarters, probably relating to his pending appointment to Brigadier General and permanent command of Posey’s Brigade.

(touch image to see the whole page)

Most of the pages are now illegible. Only the first two, detailing his dates of promotion and absence are clear. The rest report his “campaigns, battles, and skirmishes” – I wish I could read them.

I found this document among the papers in his Compiled Service Records, at the National Archives, online from fold3.

Heroic sons of Augusta, Maine (1881)

24 February 2023

17 year old Private Elisha S Fargo of the 7th Maine Infantry was slightly wounded at Antietam in September 1862, but was not so lucky at Spotsylvania Court House, VA in May 1864. He was reported wounded there and missing afterward – vanishing from the record. It is likely he was killed.

In 1881 his name was listed on the new Civil War memorial in Augusta, ME dedicated to the men of that city who never came home …

In honor of her heroic sons who died in the War for the Union and to commend their example to succeeding generations

Notes

The plaque above is on one side of the monument, and was photographed for the Historical Marker Database (HMDB) by William Fischer, Jr. of Scranton, PA.

V.E. Turner on the 23rd North Carolina

22 February 2023

Adjutant and later Quartermaster of the 23rd North Carolina Infantry V.E. (Vines Edmunds) Turner wrote the brief history of his regiment for Walter Clark’s Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-’65 (Vol. II, 1901).

Here are a couple of excepts from his experience on the Maryland Campaign of September 1862:

[at Fox’s Gap on 14 September]

… Colonel Christie seeing that a still stronger force which was advancing against him could, while engaging his front, envelop his left, sent his Adjutant, V. E. Turner (the writer of this) to apprize General Garland of the situation. Finding that Garland had fallen, the Adjutant, making his way towards the rear of the Thirteenth and Twentieth, delivered the message to Colonel McRae, then in command of the brigade. Colonel McRae having no horse or Staff (General Garland’s Staff having gone off with his body) had no means of immediate communication with General Hill, and was unable to fill the gap and to avert the disaster apprehended by Colonel Christie.

The returning Adjutant after almost running into the hostile lines, reached the position of the Twenty-third just as it was abandoned. Colonel Christie, with his short, weak line, hopelessly enveloped and enfiladed, and seeing capture sure if he remained longer, had ordered the regiment to withdraw. This withdrawal, as it had to be precipitate in the extreme, was effected in great disorder down the steep and bewildering mountain side …

[at Sharpsburg on 17 September]

The Twenty-third regiment was here able to muster but few men, many being barefoot and absolutely unable to keep up in the forced marches over rough and stony roads. The brigade which since Garland’s fall, had been under the command of Colonel McRae, of the Fifth, went into action with Colquitt’s brigade in the Confederate center, and were advancing in perfect steadiness under a heavy artillery fire from the opposite hills, till the unaccountable “run back” occurred. This happened as follows: The Federals advanced against us in dense lines through a corn field, which concealed the uniforms, though their flags and mounted officers could be seen plainly above the corn tassels. As the blue line became more distinct, approaching the edge of the corn field, which brought it in our range, we commenced to fire and effectively held it in check. But some of Early’s men, who had come from the corn field, begged us not to fire, saying that their men were in our front. Some one in a regiment to the right of us also shouted: “Cease firing. You are shooting your own men.” Hands were also seen waving the line back. This confused the men. The artillery fire grew constantly hotter. Several of the regiments, nearly exterminated at Williamsburg, Seven Pines and Malvern Hill, had been recruited with raw men, largely ignorant of discipline and of the machine-like duties of a soldier.

At this the regiments on our right began to fall back, straggling through the woods in our rear. But we could plainly see that we were not firing on our friends, and in our front the enemy was firmly held in check, till we found that they were moving on our flank unopposed. This compelled us to retire, which was done in good order, considering the circumstances. The greater part of our regiment stopped in a sunken road (the famous Bloody Lane) and joining the main line there, fought the remainder of the day. General Hill says distinctly that the Twenty-third was kept intact and moved to the sunken road.

Notes

Clark’s Histories are available online from the Internet Archive: Vol I | Vol. II | Vol. III | Vol. IV | Vol. V

Captain Turner’s picture here is from Clark as well.

Major James Wren of Pottsville

21 February 2023

James Wren led Company B of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry on South Mountain and at Antietam in September 1862 and was promoted to Major of the regiment soon after. Here he is from Bosbyshell’s regimental history (1895):

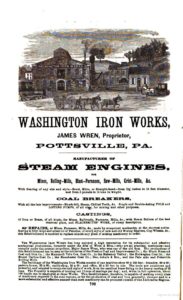

Born into an iron working family in Scotland, he and his older brothers operated the Washington Iron Works in Pottsville, PA before the war. Here’s a page from Daddow and Bannan’s trade book Coal, Iron, and Oil (1866).

James was also pre-war Captain of a militia unit – the Washington Artillery – which was one of the First Defenders of Washington, DC in April 1861. Famously, his orderly, 65 year old former slave Nicholas Biddle (c. 1795-1876), was injured by a mob in Baltimore enroute to Washington on 18 April 1861, perhaps the first man wounded in the war.

Here’s Biddle in a photograph he sold in quantity to raise funds in 1864; this copy from the Library of Congress. See much more about him and that picture from Elizabeth Nosari, archivist at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Wren is probably best remembered by Civil War historians today for a diary he kept between February and December 1862. John Michael Priest and his South Hagerstown High School students published it as Captain James Wren’s Civil War Diary: From New Bern to Fredericksburg in 1990.

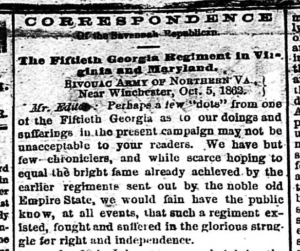

The Fiftieth Georgia Regiment in Virginia and Maryland. (1862)

20 February 2023

The beginning of a letter of 5 October 1862 to the editor of the Savannah Republican from Lieutenant Peter A. S. McGlashan of Company E detailing his experience with the 50th Georgia Infantry on South Mountain and at Sharpsburg in September 1862. It was printed in the 16 October edition on page 2, column 2. The complete article is clipped below (touch any section to enlarge).

Here’s McGlashan in about 1864, by then Colonel of the regiment, in a photograph from the Thomasville (GA) History Center.

Note

The photograph and complete newspaper are online thanks to the Digital Library of Georgia.

Kendall’s Mills, ME (1860)

16 February 2023

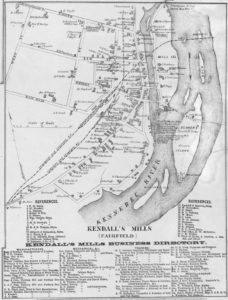

Kendall’s Mills in Fairfield, Somerset County, Maine (touch to enlarge). Hometown of Lieutenant Augustus F. Emery of Companies E and D of the 7th Maine Infantry, 1861-1864.

Homes of others of the regiment are probably shown on the map. I found at least one: Seldon Connor, at Elm and Newhall Streets, was later Colonel of the Seventh (January 1864) and Governor of Maine (1876-79).

This lovely piece is but a small detail from a very large scale map of Somerset County in 1860 created by engineer J. Chase, Jr and printed by W.H. Rease in Philadelphia, PA, now at the Library of Congress.

I recommend it to my fellow students of the Regiment.