Who commanded the 19th Mississippi at Sharpsburg?

27 February 2023

In his invaluable manuscript history of the Maryland Campaign of 1862, General Ezra Carman asserted that Captain Nathaniel W. [H.] Harris commanded the 19th Mississippi Infantry at Sharpsburg on 17 September 1862 and was wounded in action there.

If he had been there he would have been the senior officer present, as all 3 field officers were absent sick or wounded.

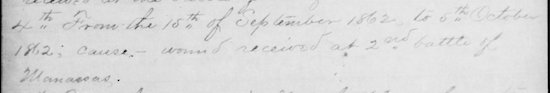

But he was not there. He later wrote that he was absent [f]rom the 15th of September 1862 to 5th October 1862; cause – wound received at 2nd battle of Manassas. It’s not clear where he was from about 30 August to 15 September, but probably not with his unit then, either.

Unfortunately, I’ve not yet found who did, in fact, command the regiment at Sharpsburg.

Here’s Harris’ statement in an extract from the second of a 7 page military resume he submitted on 2 January 1864 at the request of (Anderson’s) Division Headquarters, probably relating to his pending appointment to Brigadier General and permanent command of Posey’s Brigade.

(touch image to see the whole page)

Most of the pages are now illegible. Only the first two, detailing his dates of promotion and absence are clear. The rest report his “campaigns, battles, and skirmishes” – I wish I could read them.

I found this document among the papers in his Compiled Service Records, at the National Archives, online from fold3.

Heroic sons of Augusta, Maine (1881)

24 February 2023

17 year old Private Elisha S Fargo of the 7th Maine Infantry was slightly wounded at Antietam in September 1862, but was not so lucky at Spotsylvania Court House, VA in May 1864. He was reported wounded there and missing afterward – vanishing from the record. It is likely he was killed.

In 1881 his name was listed on the new Civil War memorial in Augusta, ME dedicated to the men of that city who never came home …

In honor of her heroic sons who died in the War for the Union and to commend their example to succeeding generations

Notes

The plaque above is on one side of the monument, and was photographed for the Historical Marker Database (HMDB) by William Fischer, Jr. of Scranton, PA.

V.E. Turner on the 23rd North Carolina

22 February 2023

Adjutant and later Quartermaster of the 23rd North Carolina Infantry V.E. (Vines Edmunds) Turner wrote the brief history of his regiment for Walter Clark’s Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-’65 (Vol. II, 1901).

Here are a couple of excepts from his experience on the Maryland Campaign of September 1862:

[at Fox’s Gap on 14 September]

… Colonel Christie seeing that a still stronger force which was advancing against him could, while engaging his front, envelop his left, sent his Adjutant, V. E. Turner (the writer of this) to apprize General Garland of the situation. Finding that Garland had fallen, the Adjutant, making his way towards the rear of the Thirteenth and Twentieth, delivered the message to Colonel McRae, then in command of the brigade. Colonel McRae having no horse or Staff (General Garland’s Staff having gone off with his body) had no means of immediate communication with General Hill, and was unable to fill the gap and to avert the disaster apprehended by Colonel Christie.

The returning Adjutant after almost running into the hostile lines, reached the position of the Twenty-third just as it was abandoned. Colonel Christie, with his short, weak line, hopelessly enveloped and enfiladed, and seeing capture sure if he remained longer, had ordered the regiment to withdraw. This withdrawal, as it had to be precipitate in the extreme, was effected in great disorder down the steep and bewildering mountain side …

[at Sharpsburg on 17 September]

The Twenty-third regiment was here able to muster but few men, many being barefoot and absolutely unable to keep up in the forced marches over rough and stony roads. The brigade which since Garland’s fall, had been under the command of Colonel McRae, of the Fifth, went into action with Colquitt’s brigade in the Confederate center, and were advancing in perfect steadiness under a heavy artillery fire from the opposite hills, till the unaccountable “run back” occurred. This happened as follows: The Federals advanced against us in dense lines through a corn field, which concealed the uniforms, though their flags and mounted officers could be seen plainly above the corn tassels. As the blue line became more distinct, approaching the edge of the corn field, which brought it in our range, we commenced to fire and effectively held it in check. But some of Early’s men, who had come from the corn field, begged us not to fire, saying that their men were in our front. Some one in a regiment to the right of us also shouted: “Cease firing. You are shooting your own men.” Hands were also seen waving the line back. This confused the men. The artillery fire grew constantly hotter. Several of the regiments, nearly exterminated at Williamsburg, Seven Pines and Malvern Hill, had been recruited with raw men, largely ignorant of discipline and of the machine-like duties of a soldier.

At this the regiments on our right began to fall back, straggling through the woods in our rear. But we could plainly see that we were not firing on our friends, and in our front the enemy was firmly held in check, till we found that they were moving on our flank unopposed. This compelled us to retire, which was done in good order, considering the circumstances. The greater part of our regiment stopped in a sunken road (the famous Bloody Lane) and joining the main line there, fought the remainder of the day. General Hill says distinctly that the Twenty-third was kept intact and moved to the sunken road.

Notes

Clark’s Histories are available online from the Internet Archive: Vol I | Vol. II | Vol. III | Vol. IV | Vol. V

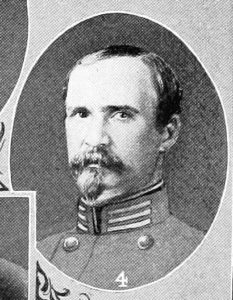

Captain Turner’s picture here is from Clark as well.

Major James Wren of Pottsville

21 February 2023

James Wren led Company B of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry on South Mountain and at Antietam in September 1862 and was promoted to Major of the regiment soon after. Here he is from Bosbyshell’s regimental history (1895):

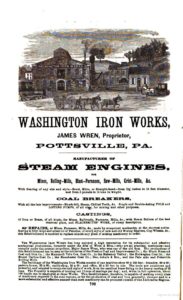

Born into an iron working family in Scotland, he and his older brothers operated the Washington Iron Works in Pottsville, PA before the war. Here’s a page from Daddow and Bannan’s trade book Coal, Iron, and Oil (1866).

James was also pre-war Captain of a militia unit – the Washington Artillery – which was one of the First Defenders of Washington, DC in April 1861. Famously, his orderly, 65 year old former slave Nicholas Biddle (c. 1795-1876), was injured by a mob in Baltimore enroute to Washington on 18 April 1861, perhaps the first man wounded in the war.

Here’s Biddle in a photograph he sold in quantity to raise funds in 1864; this copy from the Library of Congress. See much more about him and that picture from Elizabeth Nosari, archivist at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Wren is probably best remembered by Civil War historians today for a diary he kept between February and December 1862. John Michael Priest and his South Hagerstown High School students published it as Captain James Wren’s Civil War Diary: From New Bern to Fredericksburg in 1990.

The Fiftieth Georgia Regiment in Virginia and Maryland. (1862)

20 February 2023

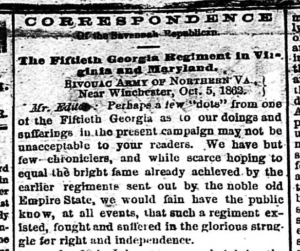

The beginning of a letter of 5 October 1862 to the editor of the Savannah Republican from Lieutenant Peter A. S. McGlashan of Company E detailing his experience with the 50th Georgia Infantry on South Mountain and at Sharpsburg in September 1862. It was printed in the 16 October edition on page 2, column 2. The complete article is clipped below (touch any section to enlarge).

Here’s McGlashan in about 1864, by then Colonel of the regiment, in a photograph from the Thomasville (GA) History Center.

Note

The photograph and complete newspaper are online thanks to the Digital Library of Georgia.

Kendall’s Mills, ME (1860)

16 February 2023

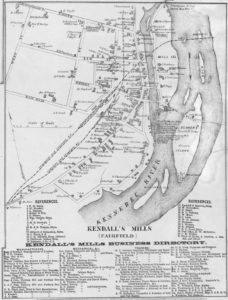

Kendall’s Mills in Fairfield, Somerset County, Maine (touch to enlarge). Hometown of Lieutenant Augustus F. Emery of Companies E and D of the 7th Maine Infantry, 1861-1864.

Homes of others of the regiment are probably shown on the map. I found at least one: Seldon Connor, at Elm and Newhall Streets, was later Colonel of the Seventh (January 1864) and Governor of Maine (1876-79).

This lovely piece is but a small detail from a very large scale map of Somerset County in 1860 created by engineer J. Chase, Jr and printed by W.H. Rease in Philadelphia, PA, now at the Library of Congress.

I recommend it to my fellow students of the Regiment.

New map and a minor re-org

13 February 2023

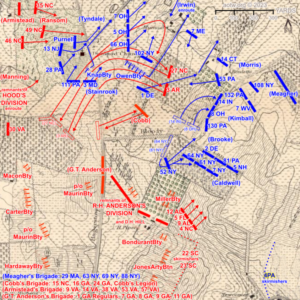

It had been nearly 20 years since I last added a battle map segment to Antietam on the Web, and now I’ve put up two new ones in two days. I felt the call to do the first one as I began a deep dive into the men of the 7th Maine Infantry [previous blog post], and the second follows from some excellent field walks and discussions at the Antietam Institute Fall Conference last October.

That second new map covers a series of disjointed but remarkably effective Confederate counter-attacks near the center of their position at Sharpsburg about noon on 17 September 1862. Most ended quickly in apparently bloody failure, but taken together they were a strategic success: critical to keeping the Federals from advancing much beyond the Bloody Lane that afternoon.

[Battle Map #10 on AotW]

While I was at it, I re-ordered the 15 map sections in approximately chronological rather than simply north-to-south order, and replaced the old top-level “menu” map with this one:

[from the main Battle Map page on AotW]

I hope this sequence encourages viewers to think a little differently about the combat events of 17 September 1862.

So what neglected action or part of the field should I do next?

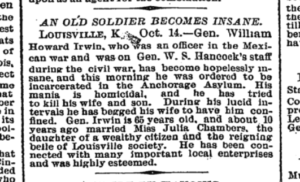

An old soldier becomes insane (1885)

10 February 2023

Colonel William Howard Irwin commanded a brigade in the Federal 6th Corps at Antietam, and is perhaps best known as the man who, possibly under the influence of alcohol, ordered a reckless charge by the 7th Maine Infantry there on Confederates on the Piper Farm.

He was wounded, sick, and “exhausted” when he resigned his commission in October 1863. He had hoped the President would appoint him Brigadier General, but that never happened …

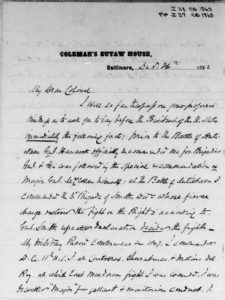

… prior to the battle of Antietam Genl. Hancock officially recommended me for Brigadier Genl. + this was followed by the special recommendation of Major Genl. McClellan himself … My friends in the Army + Penna believe that my name has been studiously kept back from the President, or that some malignant enemy has poisoned his mind against me. You know my Dear McKean what my reputation as a soldier + a gentleman is + I know you will gladly bring my claim before the President. My military record is without a stain + altho’ I am no saint yet no dishonor or disreputable practice can be laid to my charge. Will you ask the President at once to write to me at Lewiston Pennsylvania?

He returned to the practice of law in his hometown of Lewiston, then, by 1873, moved his practice to Louisville, KY, where he married a society belle and had a son. Sadly, by 1885 his mental condition had deteriorated.

He died at the asylum in Anchorage, KY not long after at about 68 years old.

Notes

The news clip is from the New York Times of 15 October 1885.

The quotes here from a letter of his of 26 December 1862, from Baltimore, to Colonel J.B. [James Bedell] McKean, 77th New York, in Washington. It’s now at the National Archives among Letters received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1863-1870, online via fold3 (touch to enlarge):

The charge of the 7th Maine at Antietam

10 February 2023

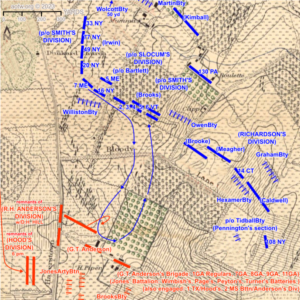

One of the saddest stories of Antietam is that of the vain heroism of the men of the 7th Maine Infantry on the Piper Farm at about 5 pm on 17 September 1862. Their ill-considered charge there destroyed the regiment as a fighting force and obtained little result.

[Battle Map #15 on AotW]

Their commander, Major Thomas Worcester Hyde of Bath, Maine, described it in his after-action report 2 days after the battle and refined his narrative in his later memoir Following the Greek Cross, or, Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (1894), which I’m excerpting here to accompany a new battle map on AotW.

Colonel Irvin [William H Irwin] of the 49th Pennsylvania commanded our brigade at Antietam. He was a soldier of the Mexican War, and had been wounded at Resaca de la Palma. He was a gallant man, but drank too much, of which I was then unaware.

read the rest of this entry »

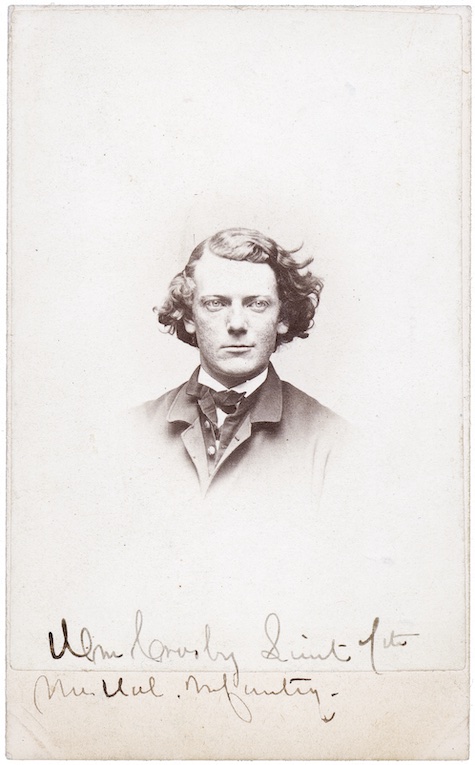

Willie Crosby (c. 1861)

7 February 2023

William Crosby enlisted as a Sergeant in the 7th Maine Infantry in August 1861, then an 18 year old student living with his parents and siblings in Bangor, Maine.

He was described as being 5′ 10″ tall, brown haired, with light complexion and blue eyes. No doubt about those eyes.

He was Captain of his Company by the end of the war, and also had service in the US Veteran Volunteers, and after the war, was a Regular Army officer until discharged in 1874.

This stunning photograph (touch to enlarge) is from the Maine State Archives and is online with nearly 2,500 other Civil War Era Soldiers’ Portraits through the Digital Maine project.