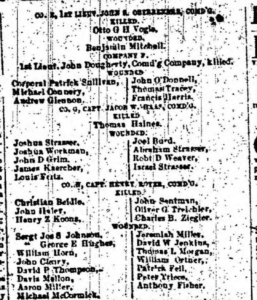

Crampton’s Gap casualty list, 96th Pennsylvania Infantry

31 August 2024

Appended to Colonel Cake’s official report as printed on page 2 of the Pottsville (PA) Miner’s Journal of Saturday, 4 October 1862, is his list of the men of his 96th Pennsylvania Infantry who were killed or wounded in the fight at Crampton’s Gap on South Mountain on 14 September 1862. It’s not found in the Official Records in company with the Colonel’s report.

My transcription of the text and links to the individual soldiers’ pages on AotW, after the jump …

Maryes in Maryland

8 April 2024

Here’s Lieutenant Edward A. Marye‘s (probably pronounced “Mary”) family home in Fredericksburg, VA as it looked in May 1864, then in use as a Union military hospital for troops wounded during the battle of the Wilderness.

First Lieutenant E.A. Marye (1862)

His father John Lawrence Marye (1798-1868), a successful lawyer and mill owner, bought land and a small house on a hill overlooking Fredericksburg in about 1824. He improved the house and named it Brompton, after the Middlesex village in England from which his Hugenot-Norman great-grandfather Rev. James Marye (or Jacques Marie, 1692-1768) came to America in about 1730.

The high ground around it became known as Marye’s Heights – now famous for the combat there in December 1862.

Lt. Edward Marye commanded a section of 2 3-inch Ordnance rifles of the Fredericksburg Artillery (Brig. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Division) at Harpers Ferry (14-16 September) and Shepherdstown (19 September), and led the battery at least part of the day at Sharpsburg (17 September) while Captain Carter M Braxton acted as Hill’s chief of artillery.

But there were also 4 other Maryes in the battery …

Private Alfred James Marye, Edward’s nephew, was on the Maryland Campaign and was wounded by counter-battery fire at Boteler’s Ford on the Potomac on 19 September. He was barely 16 years old. He served with the battery to the end of the war and was afterward a railroad clerk in Montgomery County, VA.

Private Alexander Stuart Marye (1841-1915), a younger brother of Edward’s, enlisted in the battery in June 1862 and was probably in Maryland in September. He was on detail away from his unit on ordnance and administrative duties for most of the rest of the war and was surrendered and paroled at Greensboro, NC in May 1865.

John Lawrence Marye, Jr. (1823-1902), also Edward’s brother, enlisted as a Private in April 1861 and was promoted to 5th Sergeant in April 1862. He was absent, sick into October 1862, so probably not in Maryland, but was surrendered and paroled with the battery at Appomattox Court House, VA on 9 April 1865. During the war he also served in the Virginia House of Delegates (1863-65). He’d been a wealthy lawyer and farmer in his own right before the war, and Mayor of Fredericksburg in 1853-54. He was afterward again a Delegate (to 1868) and Lieutenant Governor of Virginia (1870-74).

Another of Edward’s nephews, his oldest brother James’ son Private William Nelson Marye (1841-1929) enlisted in Braxton’s Mounted Artillery (later Fredericksburg Light) on 12 May 1861, but was detached from his unit for much of 1862 and probably not with them in Maryland. He was with the battery from March 1863 to September 1864, when he was again detailed, as a clerk to a military court for the 3rd Army Corps, but was back by Appomattox in April 1865.

To complete Edward’s story: he was promoted to Captain and it became his battery in March 1863, but he did not survive the war; he died of disease in Petersburg, VA in October 1864.

Notes

The photograph above of the Marye house “Brompton” is from the Library of Congress.

Details about Brompton from its National Register of Historic Places nomination form [pdf]. The home was acquired by Mary Washington College (now University) in 1947 and it is now their president’s residence.

Lieutenant Edward Marye’s picture here is an ambrotype in the collection of the American Civil War Museum, Richmond.

The Maryes’ military records are found in the US War Department’s Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers, Record Group No. 109, Washington DC: US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Twelve hundred pounds of corn

18 March 2024

While going through documents in Captain Robert Boyce‘s Consolidated Service Record (CSR) jacket, I came upon this receipt dated “Camp in the field Sept 23d 1862.”

My transcription:

Rec’d of Capt C. McRae Selph aſs [asst] Quartermaster C.S.A. the following articles viz –

Sept 12th 1200# Twelve hundred pounds of corn.

” 13th 1170# Eleven hundred + Seventy pounds of corn.

” 14th 1120# Eleven hundred + Twenty ” of corn.R. Boyce

Capt Lt Battery

Boyce commanded a six-gun battery of the Macbeth Light Artillery on the Maryland Campaign of 1862. The corn was likely forage for his horses. How many horses? A back of the envelope calculation, and I’m no expert …

Minimum 4 horses each for 12 limbers (6 guns, 6 caissons), forge wagon (total 52); Minimum 16 personal horses for Captain, 4 Lieutenants, 8 Sergeants, 2 buglers, 1 guidon; (?) spare horses; total at least 70 horses.

The receipt jumped out because it is the first I’ve seen for forage delivered to a unit while on combat service in Maryland. All sorts of research questions follow, like:

– How many army wagons did it take to haul that grain to Boyce?

– How far did those wagons travel? From Winchester, maybe?

– How long would that much grain have lasted? Assuming about 12 pounds per horse/day (or twice that if no hay) and at least 70 horses, not long.

– How much grain or other forage would all the horses of the Army of Northern Virginia have required? Were they getting it in September 1862?

– Horses cannot long live on grain alone. Was there good pasturage in Maryland? Hay was probably too bulky to transport to the combat zone.

I’d be glad to hear from logistic experts on this.

Hospital lists after Antietam

4 February 2024

On 12 October 1862 the New York Times printed lists of soldiers who died at several field hospitals near the battlefield in the 2 weeks immediately after Antietam. They contain some excellent detail I’ve not seen elsewhere, and I’m saving them here [PDF] for current and future reference.

Another in a series.

Francis Effingham Pinto was in the grain storage and transport business in Brooklyn before and after the Civil War. He had been successful as a merchant since about 1850, when he decided to sell supplies to ’49ers in California rather than mining gold himself.

He was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the 32nd New York Infantry in May 1861 and on 13 September 1862 was temporarily assigned to command their sister regiment, the 31st New York Infantry as they approached South Mountain in Maryland – the 31st having no field officers (Colonel, Lt. Colonel, Major) of their own present.

He was in command of the 31st at Crampton’s Gap on the 14th and at Antietam on 17 September, but did he also lead the 32nd New York Infantry at Antietam?

The New York State monument (1919) on the battlefield lists Colonel Roderick N Matheson and Major George F Lemon (both also longtime Californians) in command of the 32nd at Antietam. They certainly led the regiment in action at Crampton’s Gap on 14 September, but both were mortally wounded there and obviously not at Antietam 3 days later.

Lieutenant Colonel Pinto’s cemetery biography suggests he took charge of both units at Antietam. The definitive answer is probably in Pinto’s own History of the 32nd Regiment, New York Volunteers, in the Civil War, 1861-1863, and personal recollection during that period, which he published in 1895, but I’ve not found a copy yet.*

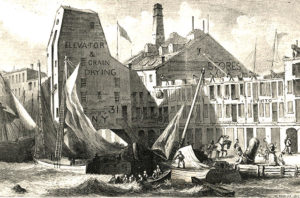

Returning to Pinto’s civilian life after the war, here’s a lovely illustration of a floating grain elevator and F.E. Pinto’s grain storage buildings in Atlantic Basin, Brooklyn, NY in 1871.

Notes

Colonel Pinto’s photograph is from the MOLLUS Massachusetts album, online from the US Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks.

The picture of Pinto’s stores in Brooklyn is from Harper’s Weekly of 20 May 1871 and was shared online by Maggie Land Blanck.

* Update

As Dave Henry notes in his comment below, Harry Smeltzer found a typescript copy of Pinto’s History and has kindly posted it [pdf] on Bull Runnings. In it, Pinto says

On the morning of the 17th … [a] committee of officers from my old regiment, the 32nd N.Y., went to Gen. Newton and requested him to send me back to the 32nd Regt, Col. Matheson and Major Lamon having been wounded at Crampton’s Gap. The Regt. was without a field officer. He assented to their wishes, and I unexpectedly received orders to join my gallant old Regiment. This change left the 31st Regt. under the command of their Major, which was not pleasant to the officers.

The charge of the 7th Maine at Antietam

10 February 2023

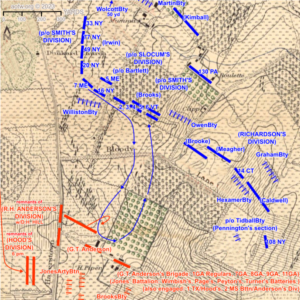

One of the saddest stories of Antietam is that of the vain heroism of the men of the 7th Maine Infantry on the Piper Farm at about 5 pm on 17 September 1862. Their ill-considered charge there destroyed the regiment as a fighting force and obtained little result.

[Battle Map #15 on AotW]

Their commander, Major Thomas Worcester Hyde of Bath, Maine, described it in his after-action report 2 days after the battle and refined his narrative in his later memoir Following the Greek Cross, or, Memories of the Sixth Army Corps (1894), which I’m excerpting here to accompany a new battle map on AotW.

Colonel Irvin [William H Irwin] of the 49th Pennsylvania commanded our brigade at Antietam. He was a soldier of the Mexican War, and had been wounded at Resaca de la Palma. He was a gallant man, but drank too much, of which I was then unaware.

read the rest of this entry »

National Cemetery serendipity

29 April 2022

As I’ve done on my last several trips to the battlefield, I stopped to visit a few stones in Antietam National Cemetery this past week. Starting at the “back” – the south wall of the cemetery – I noticed particularly the rows of markers for the many unknown soldier buried there …

As you probably know, nearly all 1890 United States Census records were destroyed in a fire in 1921 leaving a permanent information gap familiar to historians and genealogists. Not so familiar, I expect, are a set of special veteran’s schedules the Bureau collected during the 1890 Census, most of which survived.

This Special Schedule was particularly valuable to me in learning about a mystery soldier of the 16th Connecticut Infantry.

He enlisted as Lewis Bulgick, a Private in Company H in August 1862, was wounded at Antietam on 17 September, and was discharged from the service for disability in February 1863.

I spent quite a bit of time trying to learn more about Private Bulgick, with little luck. Other regimental researchers before me have had this same problem – all the way back to his fellow veterans in the 1890s. I found a little for him in Massachusetts records of the 1860s and 70s, but nothing about his ancestry, birth, or death.

Then I stumbled upon a page of the 1890 Special Schedule for Southbridge, MA. Here it is (click to enlarge):

There on row 35 is the key: he also used the alias Louis Bolduc, his birth name, it turns out. With that I was easily able to find his Québécois parents and 17 (!) siblings, birth and death information, the works. Very satisfying.

I do not know why he used the Bulgick name instead of the one he was born with – but I believe he consciously chose it, it’s not just a phonetic mis-transcription: in addition to enlisting as Bulgick, he also gave that name to the 1860 and 1870 census enumerators and the Massachusetts towns where some of his 8 or more babies were born. Some of his children seem to have later used Bulgick (or variations) and some Bolduc.

______________________

For much more detail about the history of the 1890 Special Schedule, see First in the Path of the Firemen by Kelee Blake in the National Archives’ journal Prologue for Spring 1996.

I got my copy of this particular page from Ancestry.com.

Why the Union Army Did Not Win at Antietam.

10 November 2021

Sergeant Patrick Breen fought with Company C of the 2nd United States Infantry above the Middle Bridge at Antietam on the afternoon of 17 September 1862, and two days later at Boteler’s Ford near Shepherdstown.

Many years later, in 1895, he wrote a piece for the National Tribune – a Washington, DC newspaper which catered to Civil War veterans – suggesting how differently the battle at Antietam would have ended, if only …

Following is a transcription with the accompanying illustrations:

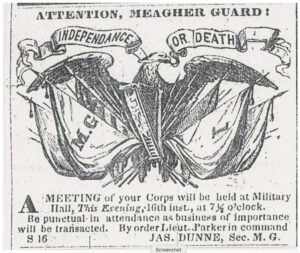

Attention, Meagher Guard! (1853)

7 March 2021

I’m exploring another Irish unit today – Company K of the First South Carolina Infantry (McCreary’s). Formed in June 1861 as the Irish Volunteers for the War, they came largely from a pre-war militia company organized in Charleston in about 1853: the Meagher Guards.

When the Guards’ idol and namesake Thomas F. Meagher began recruiting Irishmen for the Union in New York in 1861

the Charleston company condemned Meagher for “taking arms against us in this most unholy war in support of usurpation and oppression,” struck his name off their roll of honorary members, and on 9 May changed the unit’s name to Emerald Light Infantry.

Two former officers the Meagher Guard who formed the Irish Volunteers for the War – Company K – were wounded at Sharpsburg in September 1862:

Dublin-born Captain Michael P. Parker was a carpenter who “had acquired an education beyond his circumstances. He was an able mathematician, and an excellent writer.” Formerly First Lieutenant of the Meagher Guards, he was made Captain of Company K in January 1862. He was “dreadfully” wounded at Sharpsburg, and never really recovered, dying young at about age 35 in 1868.

First Lieutenant James Armstrong, Jr. was only slightly hurt at Sharpsburg and was eventually promoted to Captain of the Company after Parker. He was born in Philadelphia of immigrant parents but was raised in Charleston and lived for some time in Ireland in the 1850s.

At least 9 more men of Company K were casualties on the Maryland Campaign and many had probably been members of the Meagher Guard; with Irish surnames like Burns, Dillon, Feeney, Holloran, Kennedy, and Sullivan.

The announcement for the Guards, above, is from the Charleston Daily Courier of 16 September 1853. I found it and the quotes above in the excellent Meagher Guard, Charleston’s Fighting Irish by Bill Bynum, published in Company Front (Issue 1, 2011) [pdf], the journal of The Society for the Preservation of the 26th Regiment North Carolina Troops.